Usually, when you think about Lotus->ke49 founder Colin Chapman, the first thing that comes to mind is innovation. It’s easy to see why as that was the business Chapman was in, the brilliant designer always looking for ways to improve his cars’ performance – usually at the cost of reliability and even safety.->ke2860 This philosophy was carried over when Chapman decided he should start building road cars. The first one, named the Elite->ke3677 (Type 14), was a small but competent two-seater which was, sadly, pulled down by certain choices made in the design department, which meant that the overall quality of the car was not quite deserving of the its own name.

It’s obvious that when you employ a number of innovations into a new product, for example the glass-reinforced-plastic monocoque, it’s bound to take off the ground somewhat harder. The trouble is that some of the Elite’s flaws carried on all the way towards the end of production which ceased in 1963. At that time, little over 1,000 had been produced, but Lotus saw the potential of dropping the GRP monocoque design and returning to a more traditional body-on-chassis construction for the Elite’s follow-up, the Elan.->ke3683 That marked the end of the original Elite’s lifespan but the name would be later revived, although its use for a 2+2 grand tourer always struck as somewhat peculiar.

Away from the road, the Elites featured prominently in circuit racing, both at club and professional level. This comes as no surprise considering that Lotus was heavily involved in racing and used certain Formula 2 components in the building process of the Elite. The car was so good in fact that it won its class at Le Mans->ke1591 no fewer than six times, adding to countless other victories all across the world.

Continue reading to learn more about the Lotus Elite.

1958 - 1963 Lotus Elite

- Make: Array

- Model: 1958 - 1963 Lotus Elite

- Engine/Motor: inline-4

- Horsepower: 95 @ 5100

- Transmission: 4-Speed Manual

- [do not use] Vehicle Model: Array

Exterior

In the days before advanced computers and wind tunnels, getting a design that was aerodynamically efficient was usually achieved by chance, rather than by following a rigorous R&D process. The Elite benefitted from such “luck,” as it’s elegant design, penned by Peter Kirwan-Taylor and improved by Frank Costin, was both pleasing to the eye and slippery at high speed. In fact, it’s drag coefficient was only 0.29 – a respectable number even by today’s standards.

The car was first presented at the 1956 London Auto Show, but it spent 1957 away from the showroom floors as it was further developed by Lotus. In spite of this in-house development, the first 250 units built at Maximar Mouldings featured severe manufacturing problems, many stress points within the GRP structure failing due to heat. This forced Lotus to move the production to Bristol where it was handled by the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

The Elite is easily distinguishable by its twin headlights up front, the radiator inlet duct that sits in between also playing a role in stabilizing the front suspension frame. The minimalistic chrome-covered bumpers offered a touch of noblesse to the car, although it looks just as good without them – as seen on the racing versions.

Interior

Given the tiny size of the car, the two passengers stay quite close together, which means it would help not to ride in the Elite with your worst enemy. This does not necessarily mean that the surrounding world looks bad when seated behind the wheel of an Elite. Not especially since the large, elegant, wooden-rimmed steering wheel dominates the driver’s view. Behind it lay no less than five dials, the whole dashboard being completed by four more knobs to the driver’s left.

Poor built quality and the fact that the Elite was also offered as a kit meant that many cars did not end up with the most welcoming interiors. The fact that the early Elites, named the S1, were rather noisy at high speed did not help either, but it was all rescued by the handling which was brilliant, meaning that the driver could concentrate not on what was around him but on the road ahead.

Drivetrain

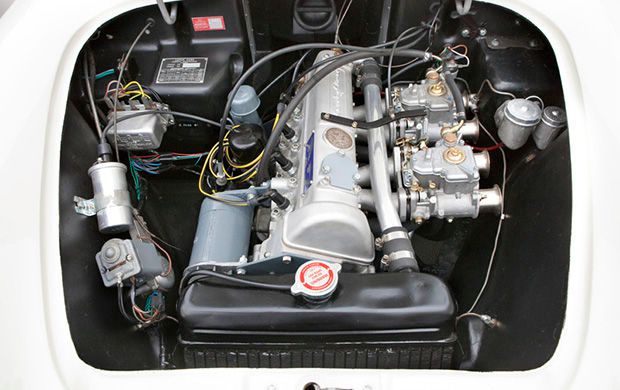

It’s not often that we speak of an engine being manufactured especially for a certain car, the more remarkable fact being that it was the only one with an overhead camshaft available on a small British sports car at the time. At its origin, the aluminum Coventry powerplant was designed for use on a portable water pump but was picked up by Lotus for its lightness and the development potential offered by the above-mentioned chain-driven overhead camshaft. With a capacity of only 1,215cmc (72.20 cubic inch), the single carburetor motor produced only 75 horsepower at 6,100 rpm in its initial form. After further development, it peaked at over 100 horses. With the car weighing in at only 1,110 pounds, the performance figures were not too shabby for the early ‘60s. The top speed was quoted at 111.8 mph by The Motor, with 60 mph being achieved 11.4 seconds.

Since Lotus was, at the time, basically a low-volume racing car builder, many components for the Elite were taken from competition cars. This is evident in the suspension, steering system and brakes which were all shared with the 1957 Formula 2 single-seater. The suspension, independent all-round, is by double wishbone at the front, the top wishbone incorporating an anti-roll bar. At the rear, the Lotus strut type suspension was employed.

The single radius arm that ran across the floor of the car on the S1 cars was replaced on the S2 by a reversed wishbone which improved cornering and directional stability at high speeds. The steering is originally from the Triumph Herald but received substantial modifications by Lotus. The braking is done by disc brakes on all four corners, the rear Girlings being mounted inboard.

The BMC B-Series gearbox was used on the S1 cars due to its low cost and reliability but was later replaced with an all-synchromesh ZF unit in the S2 examples due to the fact that the BMC one provided a rather stiff shift and had an unsynchronized first gear. This added to the cost of the car – a serious matter since Lotus was already losing money with the Elite due to its low selling price – but improved driving pleasure considerably.

Racing History

The Lotus Elite was never the kind of car to spend all its life on the road, many examples finding their way onto the racing track – some of which actually competed under the factory banner. The car’s racing debut took place at Silverstone on May 10th, 1958, with Ian Walker taking the debut win. The following day, at Mallory Park, the Elite won again. Many more victories followed that season but one race is of particular importance.

At the 1958 Boxing Day Race Meeting at Brands Hatch, a historical meeting occurred on-track: both Colin Chapman and soon-to-be Lotus driver Jim Clark raced in identical Elites. The future employer and employee raced hard for the whole distance of the sprint event, trading time spent on the 1st place. Chapman went on to win after a car that spun in front of Clark forced the Scotsman to slow down but that duel was enough to fully convince Chapman that he needed Clark aboard his ship.

The Elite proved super competitive at the 24 Hours of Le Mans as well. It first raced there in 1959 winning the 1.5-liter class and finishing 8th overall. Five more class wins followed between 1960 and 1964, three of those being 1-2’s. These wins are only the peak of the iceberg as the Elite’s racing history is long and filled with victories, privateers racing the small sports cars on five continents over the years.

Prices

The once cheap and cheerful Elite has recently gone up in price by a large amount. So much so that it’s next-to-impossible to find a good example for under $100,000. This is due, in part, to the rarity of the car but also due to the fact that the model itself is a landmark in both Lotus history and the history of British sports car. Its considerable amount of innovations make it a collector-favorite which is also aided by its cute looks.

Competition

Triumph TR3

Like most of the small British sports cars of the time, the Triumph TR3 was offered as a roadster – an option not available with the Elite due to its GRP structure. The car featured a similar power output to that of the Elite, but its less sophisticated suspension, by double A-arms and leaf springs, coupled with the iffy steering system meant it was far less of a driver’s car. This did not stop Triumph from selling the TR3, and subsequent TR3A and TR3B, until 1962. The car was also much heavier than an Elite due to its body-on-frame construction but, in spite of that, it accelerated quicker than the Lotus, but had a lower top speed.

MG MGA

The popular MGA was mainly sold outside of the English Isles, the car staying in production under different guises for seven years. In this time frame, the MGA at one point had a twin-cam engine, which offered good performance but suffered from detonation and burnt oil. The MGA 1600 and 1600A followed the Twin-Cam, the engine capacity being enlarged to little over 1.6-liters. Like the Elite, it employed an independent suspension and, originally, a four-speed gearbox. Both the MGA and the TR3 raced against the Elite on the track, the latter being usually the quicker of the bunch.

Conclusion

The lighter-than-light Elite followed word-by-word Colin Chapman’s famous words, "Simplify then add lightness," and proved that GRP could be used as a major structural element on a road car. Sadly, the same GRP is what pulled the car down, the rise in building costs and poor quality control ultimately sidelining the car in favor of the more traditional Elan. The latter proved to be a much bigger commercial success, but somehow lacked the flair of the cute Elite, now a very expensive and hard to find coupe.