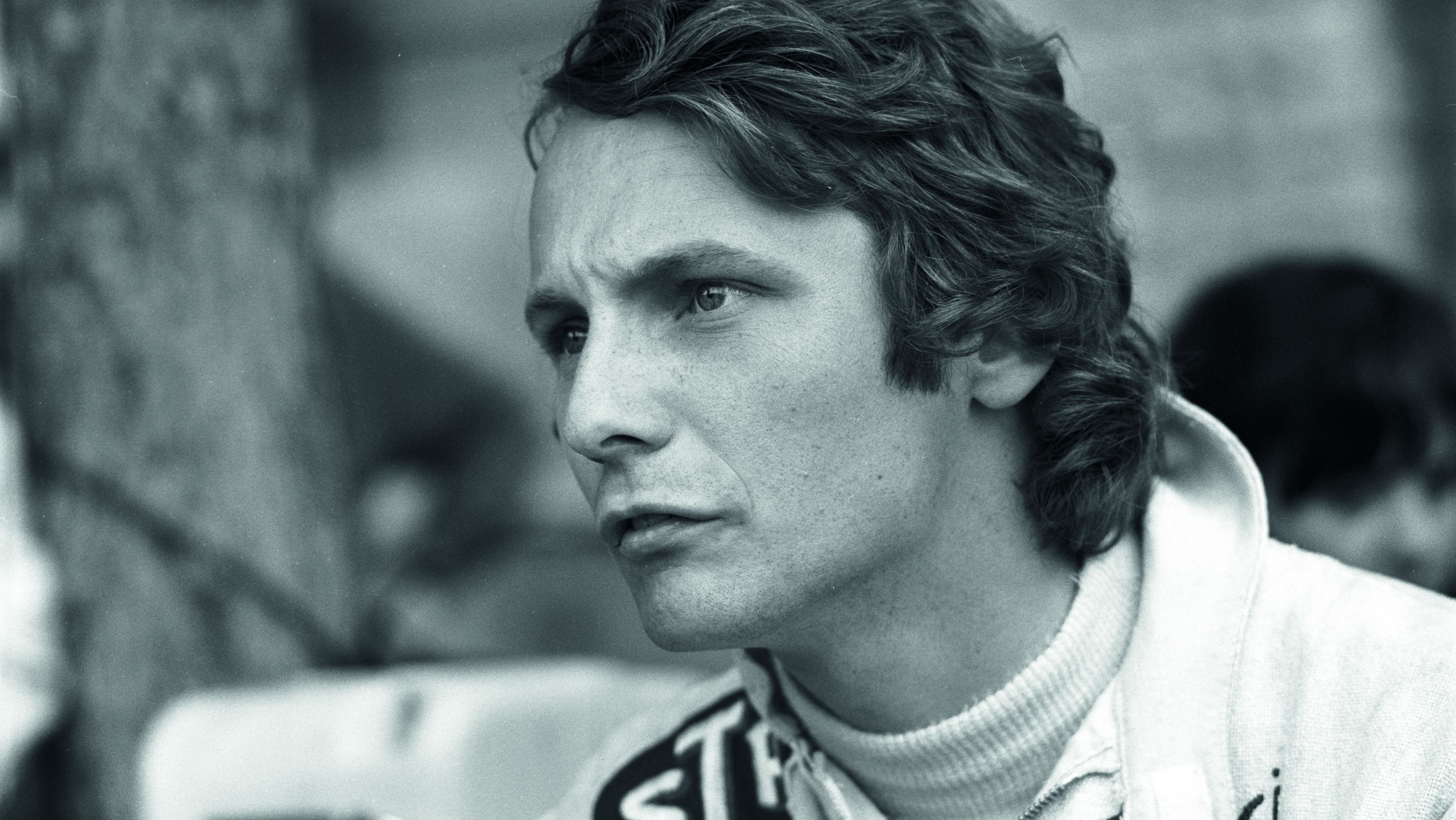

Niki Lauda, one of Formula 1's genuine heroes that survived the deadly '70s to start his own airline company and, in recent years, be a key figure behind Mercedes-AMG Petronas' success story in Formula 1 has died at the age of 70 on Monday, May 20th, 2019. The Austrian, born in Vienna in 1949, won 25 Formula 1 Grand Prix races out of 171 starts and became World Driver's Champion three times: in 1974 and 1977 for Ferrari and, again, in 1984 for McLaren. But his legacy is far greater than his sporting results for, behind the numbers, Lauda was one of the sport's shrewdest, toughest, but also most calculated and clever competitors. He carried those qualities in every area of his life, combining them with a uniquely straightforward attitude.

Monday, millions of racing fans across the globe woke up to the news that Niki Lauda was no longer with us due to complications that arose from a lung transplant as well as resurging kidney problems. Lauda underwent two kidney transplant surgeries, in 1997 and in 2005, and, last year, he underwent a successful lung transplant in the hometown of Vienna. His rehabilitation seemed to be going well, and he even spent the winter holidays in Ibiza with members of his family, but a bout of pneumonia saw Lauda return in intensive care. More recently, he'd been undergoing dialysis at the University Hospital of Zurich, in Switzerland.

Niki Lauda was, is, and will be a legend in the truest sense of the word

We often misuse words. We describe things that aren't at all amazing as such or things that produce 0% of awe as awesome. By the same token, we seem to stamp with the 'legendary' accolade many people that, while successful in their endeavors in life, don't quite qualify to be bestowed with such an honor.

If you don't think Lauda is a legend and a unique character, try to browse social media these days. Tributes are pouring in from around the world, and countless outlets that, otherwise, could care less about the world of motorized sports are dedicating countless words to honor the Austrian. I was around when other titans of Formula 1 passed on. Be it the great John Surtees, the world's only motorcycling World Champion that also became a Formula 1 World Driver's Champion (for Ferrari, in 1964), or Jack Brabham, the first and only man to win the Driver's Title in a car of his own design that bore his name and the first driver to drive to the title a car with the engine positioned aft of the cockpit, none were mourned as much as Lauda is being mourned these days. This should give you an idea of the impact Lauda has made on the world in his 70 years on this Earth.

Lauda's team-mate and title rival in 1984, Alain Prost, had this to say on the day when the tough news reached headlines the world over: "He was my idol when I started karting, during the Ferrari years," the Frenchman told AFP, quoted by Motor Sport Magazine. "There are champions and people with trophies, but we have lost a titan of the sport, who has never complained about anything - not about his life, his health, or his accident, and who always looked to the future," Prost added. The four-time world champion also described Lauda as one that'd always deliver "straight, correct and honest" with nothing to be found between the lines - a rare trait in the bustling world of F1.

Prost also describes how Lauda taught him how to disconnect and kick back while away from the track. "If I had a mechanical problem or similar issue in a Grand Prix, I used to be furious: one evening, he took me to a nightclub, and we started drinking whiskey and coke, which I had never done before. We laughed a lot, and he told me: 'You see, this helps you to forget what's happened in the past, so you won't look back tomorrow.' That was his philosophy: there was work, and there was fun. Since then, I've managed to compartmentalize my life, and it's Niki who taught me this."

Toto Wolff, Team Principal of the Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 team, which Lauda was a member of for the past six years as a non-executive Chairman, described the one nicknamed 'The Computer' as "quite simply irreplaceable." We haven't just lost a hero who staged the most remarkable comeback ever seen, but also a man who brought precious clarity, and candor to modern Formula 1. He will be greatly missed as our voice of common sense," and as a "guiding light" for the Mercedes team, Wolff added.

FIA President Jean Todt was also among the many that offered his condolences on the passing of Lauda, saying that the Austrian was someone "who inspired me in my youth. He is a milestone in the history of F1."

Lauda's career overviewt

Oftentimes, the remarkable stories of some of racing's biggest names start out decidedly bleak. Rally legend Ari Vatanen, for instance, was born in rural Finland and nobody in his family had any business with motor racing, but he pushed through and, by 1974, he'd made his debut in the World Rally Championship aged just 22. Lauda, on the other hand, could've had a smoother path to the top of the ranks since he was the member of a wealthy family, his paternal grandfather being industrialist Hans Lauda. But he didn't because his family never agreed for him to go racing.

He first became interested in all things technical as a child. "From the age of about 12 I was fascinated by the tractors and so on and, as I was the owner’s grandson, they’d let me drive," he told Motor Sport Magazine in 2017. “I used to watch racing on TV,” he added, pointing out that he was there, at the Nurburgring, when countryman Jochen Rindt finished third in the German Grand Prix of 1966. "While we were there, I was introduced to Kurt Bergmann, who built Kaimann Formula Vee cars.”

Then, in 1970, he was given the wheel of a brand-new Porsche 908/2 'Flunder' to race in the Interserie. His best result, a fifth-place finish at Thruxton, came after his first victory - at Diepholz, in Germany, in a non-championship race that featured a mixed grid of prototypes and GTs. He also finished on the podium in another non-championship race at the Nordschleife and fifth partnering with Freddy Kottulinsky in the 500-kilometer endurance race at Imola where a J.W. Automotive-entered Porsche 917K driven by Brian Redman won outright.

The following year, the Bosch Team offered him a ride in the European F2 Championship. He drove the team's March but also took part in a round of the European Sports Car 2.0-liter Championship aboard a Chevron at Salzburgring which he duly won. "I really enjoyed that weekend because Helmut Marko was the series benchmark in his Lola and I beat him. I still sometimes remind him about that," Lauda said with a sparkle in his eye. 1971 was also the year when Niki Lauda made his touring car debut with Alpina - a relationship that would endure for quite a few years because of the other debut he made that same year, namely in Formula 1.

"I now had a problem, because I’d signed a deal with March but had no money," he pointed out. Lauda first tried to get a loan at a bank that, unfortunately for him, had his own grandfather on the board of directors that would approve big loans such as the one he needed. Obviously, his grandfather rejected his own nephew's request. "I went to see him and said it was none of his business if the bank was happy to lend me the money, but he told me I should be working in business and not getting involved in a stupid, dangerous sport," Lauda recalled.

In desperate need for 2.5 million Austrian schillings, Lauda knocked on the doors of rival bank Raiffeisen that offered him a five-year no-interest loan on the condition that he'd sign up for life insurance too. All the effort seemed to amount to nothing as March's 721 was far off the pace. Ronnie Peterson, who'd joined March as 1971 Vice-Champion, finished ninth in a season dominated by Colin Chapman's Lotus 72 while Lauda scored no points at all. His best finish was seventh in the South African Grand Prix.

"Max Mosley called late in the year, told me the team was running out of money and that there wouldn’t be a seat for me in ’73." How did he get out of that one? By acting as a translator, in short. Lauda details the incredible meeting that allowed his F1 dream to continue going forward: "I called Louis Stanley at BRM and told him I might have a sponsor if there was a car available. I met him at an airport and was accompanied by the financial director of the bank that had lent me the money. He couldn’t speak much English, and Louis spoke no German, so I translated between the two. It was basically two hours of bull on my part, but in the end, we struck a deal."

Lauda was supposed to pay the first installment of his sponsorship money to BRM by the Monegasque GP, but Stanley was so impressed with Lauda's results that he offered the Austrian a deal: he'd have to pay BRM no money if he agreed to stay on for 1974 which he did. It has to be said that BRM was, at the time, on a slippery slope towards its demise. It had last won a race - by chance - in 1972 when Beltoise broke through to win a very wet Monaco Grand Prix. People thought the same thing could happen again as Lauda was running third in the Principality in '73, ahead of Ickx's Ferrari (which was a dog that year), before the gearbox gave up. This impressive display came mere weeks after Lauda finished in the points in the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder. He also fared well in sedan racing: won the first round of the ETCC (at Monza) for BMW with the new 3.0 CSL and took class honors in the 1,000-kilometer race at Spa.

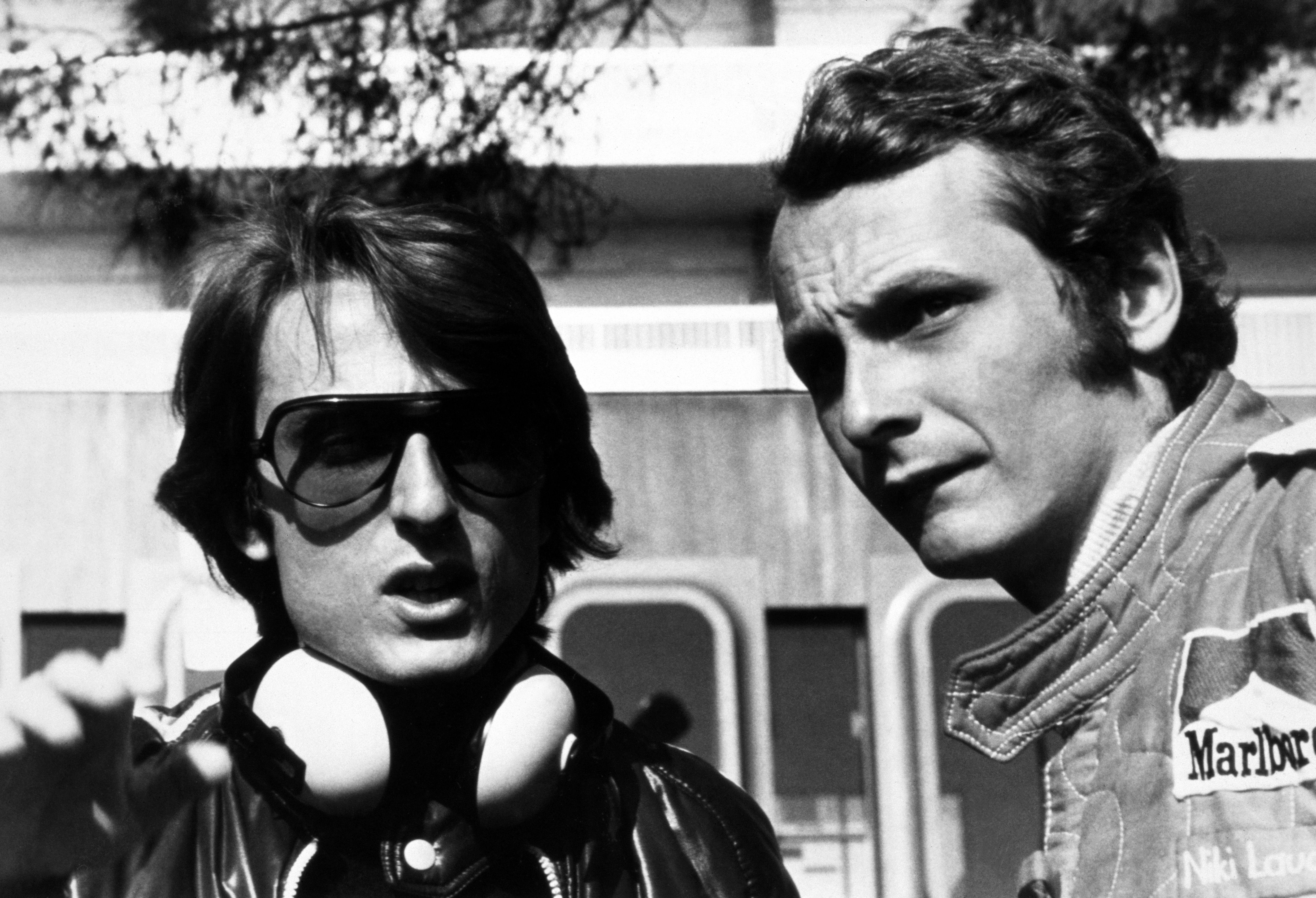

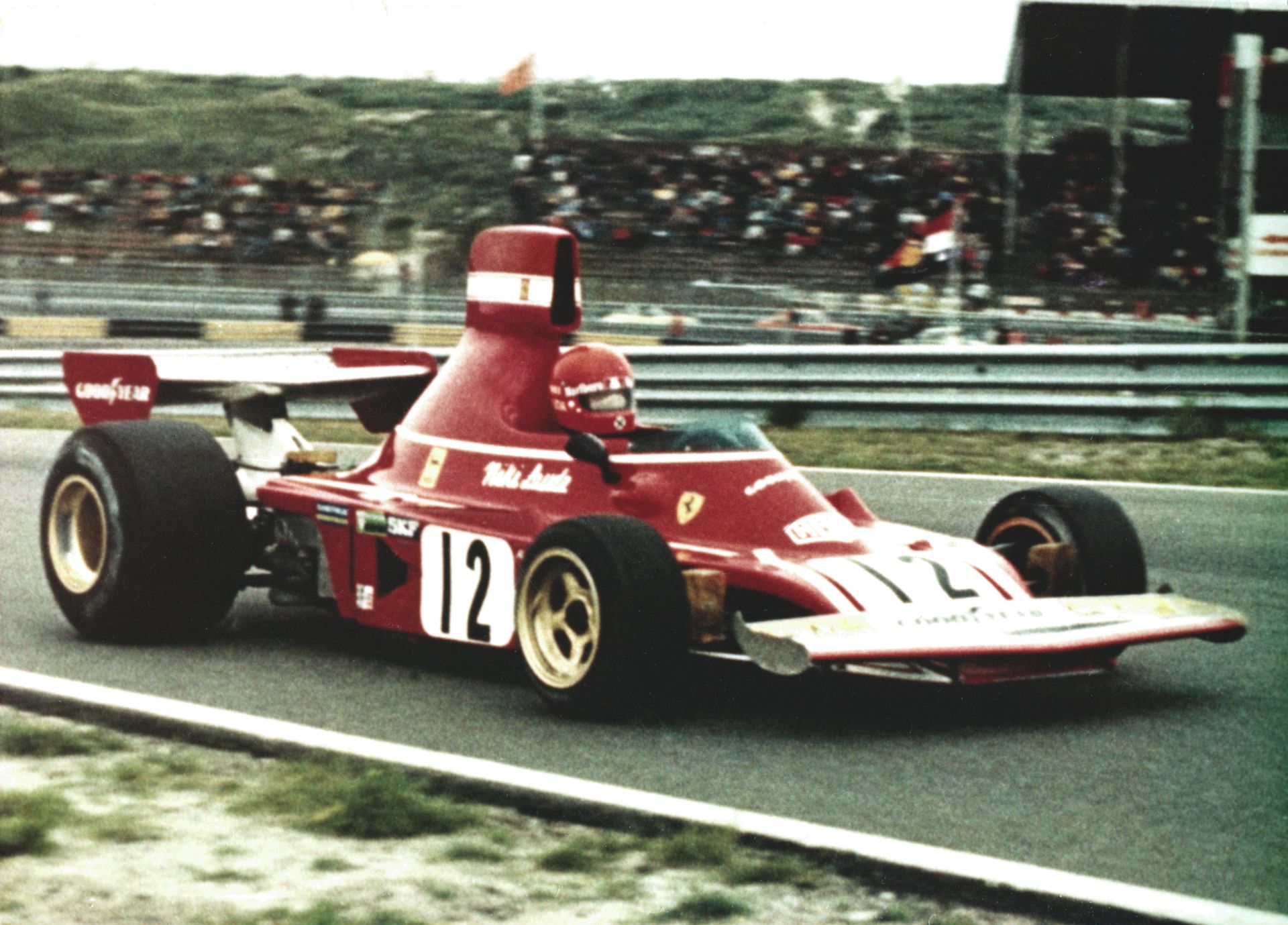

With BRM out of the way, Lauda arrived at Fiorano and was in awe at the Italian facility, so much so that he scratched his head at Ferrari's endless dry spell at the time. The Scuderia lost Ickx at the end of '73 due to the 312's poor performance, and there was little to suggest 1974 would be any different. The memories of John Surtees winning the title in '64 were beginning to fade, and Lauda quickly found out why: "I told them the car was s***." If you've watched 'Rush,' the Ron Howard-directed motion picture that centers around the rivalry between Lauda and Hunt, you'll remember this scene, which isn't the product of Hollywood's imagination.

Luckily for Lauda, the translator toned his impressions down a bit when Enzo wanted to find out about the Austrian's feedback. Keen to see what he could do, Enzo asked Lauda how faster he'd go if the engineers would get rid of the terrible understeer. "I replied ‘half a second’ – I probably should have said three tenths, but once Mauro Forghieri had revised the front suspension I found eight and from that moment I had Mr. Ferrari’s respect."

Then came the 1976 season chronicled in 'Rush,' the season that made F1 a genuine headline sport once again and that meant it would become attractive for TV broadcasters. That year, Lauda seemed to have no problem to fend off the threat of Britain's James Hunt, who became quite the sensation when he managed to win the Dutch GP of 1975 behind the wheel of a Hesketh. A consistent string of positive results got him behind the wheel of a McLaren for '76 but it was his demeanor and his off-track antics that made Hunt legendary - although he was no slouch behind the wheel.

What turned things around that year was the German Grand Prix. On the second lap, Lauda's Ferrari went off track, crashed into an embankment and was thrown back onto the track in the way of other oncoming cars. Four drivers, Brett Lunger, Arturo Merzario, Guy Edwards, and Harald Ertl, as well as a track marshal, helped Lauda out of his burning Ferrari 312T. The severity of the crash had broken the helmet's strap, and Lauda was heavily burnt on his scalp, face, and hands. At the hospital, a priest gave him the last rites, but Niki refused to let go and, despite the burns (that extended to his trachea and lungs too), he famously got back in the car in time for the Italian Grand Prix, just 40 days after his crash on August 1st, 1976. His bandages were drenched in blood after the race, but Lauda carried on regardless and finished fourth. One of the things that motivated him in his recovery was seeing James Hunt eat into his healthy advantage while he was in the hospital.

In the end, it came down to the final race at Fuji, in Japan.

One year later, Lauda bounced back and won his second and last title for Ferrari. He won three times, as did James Hunt, but a number of retirements for Hunt meant that Lauda took home the trophy by just a single point at year's end. Earlier, after his first win of the season in South Africa, Lauda spotted in the crowd of journalists at the post-race press conference one particular pundit who had the nerve to ask him, at Monza in '76, how is his personal life now that he's 'ugly.' What Lauda did is legendary: he rose his trophy, pointed at the said journalist and said: "Well, you can shove this up your ass." Later on, looking at footage of the accident and the aftermath he said, in an interview with Graham Bensinger, maybe his most quoted line: "I have a reason to look ugly. Most people don't."

But his confidence in his decision to move to Brabham for 1978 went away rather quickly and, years later, he conceded that it was the wrong call. Granted, Bernie's money was appealing and, on top of that, he left as a slap to Ferrari who'd treated him poorly after Fuji. Reutemann was tasked with leading the development program for '77 while Niki had another eye operation and nobody informed the Austrian about it. To persuade the team to let him attend the Paul Ricard test where Reutemann was putting laps in the new car, he threatened Enzo that he'd leave for McLaren although there hadn't even been a meeting between the two parties. In the end, he was allowed to attend but only on the last day of the test. "Everything felt a bit worn out after three days of running, the gearbox was shagged – everything was s***."

In spite of this, Lauda got in the car, drove a few laps, asked the team to change the angle of the wing and do some suspension changes as well and quickly found 0.6 seconds over Reutemann. "I jumped out, and the team asked what I was doing. I said, ‘I’ve found out what I needed to know and you don’t want me to test anyway…’ That set off a Ferrari panic – ‘You should test, you need to test.’ I said, ‘No, Carlos is the master of testing’ and went home."

This no-nonsense attitude was on full display towards the end of 1979 when Lauda decided to retire, telling Ecclestone he no longer wanted to "drive around in circles." What's interesting about this is that his decision to retire came shortly after battling to get the biggest ever paycheck in the whole F1 paddock at the time: $2 million per season. Initially, Bernie had none of it, offering just $500,000. "We battled for three or four months," Lauda said adding that Bernie "went around to all the other team principals saying, ‘Lauda wants two million – let’s not pay him. If one of us starts paying too much, we’ll all be screwed.’" At the time, Ecclestone had just established the Formula 1 Constructors' Association (FOCA), so he had some power in this regard. A year before, in 1978, he voluntarily retired the Brabham BT46B 'Fan Car' designed by Gordon Murray (that carried Lauda to victory in the Swedish GP) only so that rivaling manufacturers would agree to be part of his FOCA.

Project Four, Ron Dennis' outfit that had competed Formula Two and Formula Three, built some of the M1s that competed in Procar but, as an entrant, it only had one car on the grid in '79: that of Niki Lauda. The Austrian won at Monaco, Silverstone, and Hockenheim to claim the title in the Marlboro-liveried car ahead of all of the five 'works' BMW drivers that drove BS Fabrications-built chassis (Andretti and Hunt were among those in works cars). Lauda didn't return in 1980 because, after leaving Brabham, he decided to focus full time on his airline company which he founded that same year.

|

Lauda Air "initially operated passenger charter services within Europe," according to Flight Global. "To have a real challenge when I stopped racing, which was a difficult life in another way, I founded an airline," Lauda said. In 1997, Austrian Air took a controlling stake in Lauda Air which, by that time, was offering globe-trotting flights to Sydney or Hong Kong. Four years prior, Lauda founded Lauda Air Italy, but Livingston purchased it in 2003, three years after Lauda founded a third airline company, Niki (that became FlyNiki). Niki set out to be "Austria's only low-fare airline" and, until very recently, Lauda was in control of this company that had been renamed Laudamotion in 2018 after the Austrian regained control of it. Flight Global argues that "Lauda helped to bring competition and low fares to one of the highest-cost markets in Europe and, in doing so, challenged some of the airline sector's most powerful players." |

But Lauda's racing career did not end in 1979. His relationship with Ron Dennis endured, and, by the time Dennis became the boss of McLaren, Lauda's interest in racing had reignited after visits at the Austrian and Italian GP in 1981. Dennis invited Lauda to test a McLaren at Donington. While out of shape, Lauda wasn't far off the pace of John Watson, who'd been Lauda's team-mate at Brabham previously.

Watson knew already the kind of man Lauda was and the kind of persuasive skills he had. "One of the strengths that Niki has is that he’s a very astute and intelligent man and he’s a very good operator for Niki Lauda," said Watson. This was also due to his very precise feedback he'd give to engineers which, in turn, would see them gravitate towards his side of the box, according to Watson. The two were team-mates in 1982 and 1983, and it was Watson who could've become World Driver's Champion in the topsy-turvey 1982 season, although Lauda proved his worth by winning in his third race after coming back.

"In races, I was generally in better shape, could look after the tires and so on and ended up beating him to the title by half a point. It happened because I changed my way of attacking him, but the following year, he won – and he was a difficult bugger because he was so quick, no question. He was definitely the next generation, so I decided it was the right time to stop again.” His last win came at the 1985 Dutch Grand Prix and put him on even grounds with Jim Clark although the Scotsman had won his 25 GPs in far fewer outings - just 72.

After he hung up his helmet, this time for good, Lauda returned to his airline business full-time but was never too far from the F1 paddock. After his rather short-lived gig at Ferrari as a consultant, he became the manager of Jaguar Racing in 2001 but left the job after little over a year, not before trying the Ford-engine F1 car for himself. At that time, in 2002, he went on record saying modern F1 cars are so easy to drive that even a monkey could do it. Then, during the test at Valencia he spun twice, stalled the engine once, and was 15 seconds off the pace. Still, he was 51 at the time, but it goes to show that even today's F1 cars aren't something you can just strap in and go flat out with right away. Some may never be able to do that, in fact.

Further reading

Read our full review on the 2013 Ferrari 458 Niki Lauda Edition

Go Behind The Scenes of The Movie Rush

Schumi and Lauda Driven An E-Class Cabriolet