Henry Ford used to say that people started racing->ke447 from the very moment that they finished building the second car ever. Likewise, they’ve tried to figure out who’s the quickest, most daring, or most talented behind the wheel for just as long. Thus, the question of who is the best in a certain discipline is not new and there are so many tops for the existing formulas within motorsport itself that it sometimes get dizzying when you try to figure out who’s sits where in history in terms of talent, speed and other criteria.

Obviously, many will argue that it is impossible, let alone pointless, to try and rank drivers from different eras. How could you, for example, compare drivers that raced at Indy->ke3200 in front-engined roadsters->ke1418 to those that blitzed the oval with mid-engined ground-effect racers?->ke148 Or how could you compare a gladiator like Nuvolari with a modern F1->ke190 driver who is, seemingly, having to cope with a lot less while driving? It is, indeed, a hard task, as cars and tracks do change as time goes by. But, the core values that describe a great driver do not change, and the same values apply to both Fangio and Senna, or to Bernd Rosemeyer and Schumacher. And, the most important of them all is quite simple to define, because it talks about what each of them did with what they had at their disposal at a given moment in time compared to their opposition.

If we lay our founding stone there, we can easily move on and single out a certain amount of "peak’’ moments for each driver – moments when they have really shone as bright as stars – and based on those peaks we can start to organize a ranking. Indeed, many more elements come into play, but we’re fortunate enough to have had a number of drivers throughout history that were so good that they could probably be quick in any car with a little bit of time to adjust.

The story is the same for Formula 1.->ke190 With the World Championship being around since 1950 -- although the formula itself dates back to 1947 -- many drivers and cars have passed but some stand taller than others. Of course, many never did get their big break to show what they are capable of – drivers like Chris Amon, Ricardo Rodriguez or Stefan Bellof were either in the wrong place at the wrong time or they got killed before they could truly make the best of their abilities. But, there are others that have got their break and did what their talent allowed them to – become the best of their time.

These are the men we’ll be talking about in this top 10. The men that stood above the good and even the very good. The first few date back to the ‘50s while the most recent exponent is still racing in Formula 1 today. In spite of how we ranked them here, they are all, without a shadow of a doubt, all-time greats and true artists in the craft of precision high-speed driving.

Keep reading for the full story.

10. Fernando Alonso

If we were to build a bridge across time, the great "Flying Mantuan”, Tazio Nuvolari, would be the man people would talk about using roughly the same terms we use when talking about Spaniard Alonso nowadays. Obviously, the Italian’s talent and will to never give up is still worlds apart from Alonso’s, but the two can still be compared to some extent. Just like Nuvolari, Alonso fights every car he’s given in a never-before-seen style, somehow extracting every ounce of performance from the machine. This is how he’s won world titles, but, just as well, this is how he grew in the hearts of the Tifosi. He’s been consistently able to make the best of what he’s given – this is how he fought for the title in his first years at Ferrari->ke252 even if the red cars were not the best on the grid, sometimes rather far from it. He can jink from playing a tactical game, to going on a ferocious assault only the likes of Senna or Moss were able back in their days. Of course, he is not the quickest in qualifying, but in race->ke447 pace very few match him, and I’m not talking only about his current-day rivals.

9. Jackie Stewart

He was the "Robin" to Clark’s "Batman". One of the most impressive debutants, Stewart proved to be the best driver out there after Clark’s untimely demise in 1968. Until his retirement he was crowned world-champion three times and his 20-odd wins between 1968 and 1973 prove that he was a force to be reckoned with. After a scary crash at Spa in 1966, he realized that things should change. Motorsport should not be about death tolls – it should be about the sport itself. As his popularity grew and became a world-wide known figure, he started working towards ensuring that drivers will not die by the dozens each year in racing.->ke447 He used his political skills as well as his position as a leading driver to force the hand of the ruling bodies to make everything safer. People were calling out his nanny state policy at the time, but without his forceful approach, the seeds of a new era of safety might not have been planted at that time, and for that Jackie deserves a special place in motorsport’s history. What is more, when it got down to business, he took no prisoners, as his "tour de force" at a rain-soaked Nordschleife in 1968 shows. Of course, he had the better rain tires which helped him surge past the likes of a bewildered Chris Amon, but his prowess in the wet is undoubted -- Spa 1965, where he finished second to Clark, also springing to mind. But, he could be quick on a dry track as well, as the Italian GP of 1973 proves. Jackie came in early with a puncture, the ensuing a pit stop lasting a full minute, which meant that his Tyrrell was now on 20th place. A blasting drive saw him finish fourth, and as Emerson Fittipaldi failed to win, Jackie got his third world title then and there.

8. Stirling Moss

We never got to see a blue Ferrari->ke252 with a red stripe across its nose because Stirling never got to drive for the Scuderia, but his previous drives are enough to earn him a place in this ranking. Statistics enthusiasts will start mumbling the same rhetoric about his lack of world champions, but that’s due to his courteous manner, if anything. He was a pure racer, as he would steadily point out upon being called a "driver", racing->ke447 guided by instinct and an enormous talent. His clear wins at Monaco and Nurburgring in 1961, in an inferior Lotus,->ke49 prove he was always capable of driving at or beyond the limit at which most good drivers draw to a halt. His idol Juan-Manuel Fangio appointed him with the title "world champion without the crown,"’ but in his versatility, Moss exceeded even the exploits of the great Argentine. Sadly, Stirling couldn’t emulate the long career of Fangio, but in his time on the track, between 1958 and 1961, he proved to be the best, and only the arrival of a Scottish farmer named Jim Clark would make people reconsider their choice on "the best of Britain".

7. Alain Prost

What started off as a ruthless fighter, morphed into the biggest tactician in F1’->ke190s history. Prost’s evolution is closely linked to his time at McLaren->ke284 as Lauda’s team-mate, but the finesse that always stood by him was just as important in defining France’s greatest F1 driver of all times.

From his early days at Renault,->ke72 when he could carve his way through the field displaying a never-back-down attitude like he did at Kyalami in 1981, to his final spree at Williams, his qualities in the race never deserted him. But, what did change, was his approach. From the maximum-attack manner, he went on to become a strategist that would transform him into the leading driver of the first turbo era, when tire and fuel management was essential. He would plan every aspect of the race beforehand, dismissing the instinctual style of Senna who became his team-mate in 1988. At that time, Alain was already a two-time World Champion, but the Brazilian proved to be the hardest nut he ever had to crack. If Ayrton was head-and-shoulders above in qualifying, Alain could routinely outsmart Senna, which would make up for the deficit on the grid. That’s exactly what the "Professor" -- as he became known for his calculated approach that echoed the age-old saying of Fangio, that you have to win the race with the slowest speed possible -- did at Monza in 1988.

Faced with a dying car, Prost realized he needed Senna out of the running as well if he was to keep his hopes alive for the title. Knowing full well that Ayrton believes that there is no one in the world quicker than him, the Frenchman engaged himself in a cat-and-mouse game with his team mate. He started pushing as hard as he could, which was quicker than anyone else on the grid could barring for Senna, and was starting to reel in. The Brazilian got precipitated as he saw Prost’s car approaching and reacted by pushing over the limit as well. While Prost later retired, Senna kept pushing and by doing so used too much fuel. So much, in fact, that he had to slow down nearly to a crawl in the latter stages of the race which allowed the Ferraris to close up the gap. This scared Senna who tried to raise the tempo but ended up crashing in the back of Schlesser retiring. Prost’s genius plan had worked perfectly, and it was 100% fair-play. No one was able, in the sport’s history, to manage a race to perfection quite like Prost -- not even old school ace Felice Nazzaro, or his former team mate, Lauda.

6. Juan-Manuel Fangio

Ask Moss and he’d promptly tell you that Fangio is the greatest driver he’s ever seen. The Briton being the man behind much of the hype created around five-time World Champion Juan-Manuel Fangio. While obviously impressive, his statistics only improved once his main rival perished and, what is more, the Argentine only seemed to win driving the best car.

Indeed, winning titles for Ferrari,->ke252 Maserati,->ke51 Alfa-Romeo->ke1386 and Mercedes-Benz->ke187 is unique in F1’->ke190s history, but Fangio was regarded in period as second-best to Alberto Ascari, and his fame only grew after the Italian was out of the picture. But once that happened, Fangio’s superior experience made its mark in the way the Argentine planned his Sunday, never pushing more than it was necessary. That meant that he was never too harsh on his cars which were, in any case, some of the most reliable on the grid.

Fortunately for us, certain races asked for Fangio’s inner demon to come out to play and when it did, everyone could clearly see what the man was really capable of. Certainly, the Ferrari teammates Collins and Hawthorn realized it at Nurburgring in 1957, when the red Maserati 250F of the venerable Fangio stormed passed them. A similarly ferocious Fangio came to life at Monaco the year before, but there were times when Fangio seemed to lose concentration like he often did during the same 1956 season. All in all, his record speaks volumes about his professional manner in which he tackled racing and prime abilities clearly point out one of the best drivers of not only the 1950s, but of all times.

5. Ayrton Senna

Media exposure transformed Senna->ke4309 into a half-god, adored by fans all across the globe. His untimely death during the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix only added to his myth and his peak performances are viewed by his followers as a nearly religious experience. But Ayrton, unquestionably Brazil’s greatest F1 driver, had a dark side away from his awe-inspiring drives. Sometimes, when his supremacy would be questioned, he would act ruthlessly in a way that not even a robust driver like Nino Farina would dare. His tally of crashes on track is above all the others, as Stewart pointed out in a famous interview with Senna in 1990. So, when you take in the good and the bad, how can Senna be truthfully rated in the gallery of the greats?

He made a storming debut with Toleman-Hart in 1984, bewitching everyone on hand with a brilliant drive at that year’s Monaco GP. It’s safe to say that he earned a place in the back of everyone’s mind that day in spite of the fact that he wasn’t necessarily the quickest on the road. Of course, as years went by, Ayrton became known as a "Regenmeister" , a King of the Rain, having an unearthly sensibility when it came to rapid changes in grip levels in wet conditions. He had virtually no rivals when the track was drenched and races like the 1985 Portuguese GP, where Senna took his maiden win, the 1988 Japanese Grand Prix or the 1993 European Grand Prix will forever lay as evidence to the three-time world champion’s prowess.

Moreover, he was consistently able to extract the best out of any given car for qualifying. This time, the stats are telling about his nearly mystical manner in which he approached qualifying. The 1988 Monaco GP is one of those times when the Brazilian seemed to transcend what anyone could do by a mile. All of these moments helped build Senna’s image as the best driver of his decade and, due to the fact that the media was now covering every race and Ayrton became a star, his exploits are easily accessible by anyone even today – which cannot be said about Alberto Ascari or Fangio, who lived in an era before the TV set took over.

His aura, which has undoubtedly a lot of backing, means that most quit talking about his mishaps and about the times when he proved dangerous for the other drivers on the track. Senna believed that there was none better than him in F1, and as such, felt compelled to prove it every time out. While most often it would work in his favour, some other times things would not play out quite as he’d expect, and this is when his dark side would erupt. Estoril 1988, Adelaide 1989 or Hungaroring 1990 are just some of the times when Senna deliberately kicked a disobeying driver out of his way. Of course, Suzuka 1990 is the tip of the iceberg, but in his record there are many more other moments.

Thus, Senna is truly the most complex driver in F1’s history, On the one side he was one of the most spectacular and gifted drivers. His dedication and pedantry led to some of the best showcases of driver excellence in history but, on the other side, his dirty moves painted a different picture of the modern racing driver – something other than the gentleman of the 1950s and 1960s.

4. Alberto Ascari

"He was the quickest man I’ve ever seen in my life, quicker even than Fangio" was how Mike Hawthorn, the 1958 world champion, thought about Italy’s last bona fide genius. He was the first "Maestro" of the ‘50s, and could have won the 1951 title if Ferrari would not have messed up the tire and rim choice for the final race meeting. He did, however, come back and took the 1952 and 1953 titles with ease, the 500F2 being the car to beat. In fact, he was able to string nine victories starting in June 1952 with the Belgian GP. At that particular race meeting his consistency was proven by the staggeringly small difference between his quickest and slowest laps: only two km/h.

Judging purely by statistics, his 13 world championship wins and only two titles are shadowed by those who raced far longer at times when the World Championship housed many more rounds. But, when you couple those 13 wins with the total amount of official races he took part in, which is 32, the image shifts completely. If we are to take the Nordschleife, the second most demanding track in the calendar back then according to the drivers, with the first being Spa, then Ascari is the best bar none. He won there three times, helped by his consistency, precision, and ability to memorize the whole track.

His most compelling performance at the Nurburgring, that of 1953, is incredible in the way that it is reminiscent of what pe-war great, Bernd Rosemeyer, would do in the rear-engined Auto Union Type C. Ascari began by taking the pole, 20 seconds ahead of anyone else in wet conditions. Then, in the race, he steadily built up a gap which measured over 40 seconds by the time his right front wheel simply shattered on the start finish straight. In spite of the incident, Alberto was able to slow the car down and bring it to the pits where the wheel change and subsequent repairs took four endless minutes. After the work was done, Ascari left with a deficit of approximately four minutes to the leader. In spite of now having to work with a car which had functional brakes on only three wheels, the Italian managed to post a new lap record before he had to retire due to further technical problems.

Unfortunately for Ascari, the move to Lancia->ke45 for 1954 proved disastrous, as the Italians were slow developing the Vittorio Jano-designed D50. Because of that, Ascari had to miss most of the season, and when he did make it to the grid. he had to drive around in some seriously underpowered cars. In France, on the blisteringly quick Reims circuit, he started from the front row in a 250F, with the two Mercedes W196 Streamliners next to him. At Monza, a 553 was lent to him. Again faced with the speed of the W196, Ascari led easy for 40-odd laps until the engine gave up proving nonetheless that he was able to better anyone in spite of an inferior machine. Fangio reckoned, after taking the crown in 1955, that his title lost some of its value since Ascari, who died early in the year in a private test at Monza, was not around to fight him, and this speaks volumes about the value of the man who was the benchmark in the ‘50s.

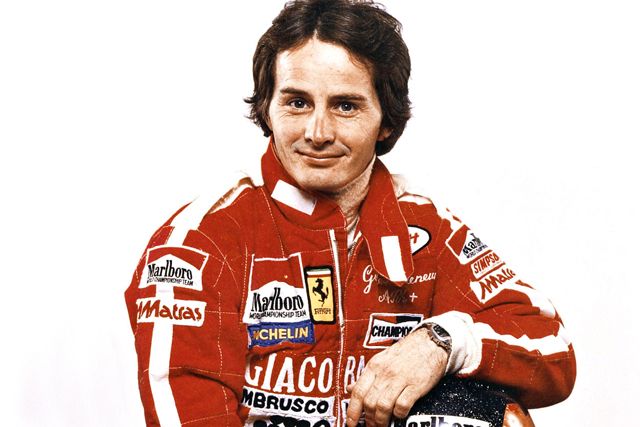

3. Gilles Villeneuve

One of the last true wild heroes of F1, Gilles Villeneuve would dance in his F1 Ferraris the same way he would on the Canadian snow on his snowmobile. His epic fight for 2nd with Rene Arnoux at Dijon in 1979 is what most recall, but his greatness goes far beyond his antics.

Reckless at the beginning, Gilles was able to rule out mistakes as his first F1 season drew to a close, being able to claim an enormously popular maiden win at the Canadian GP in ’78. Of course, it was a lucky win as Jarier’s Lotus expired late in the running, but his skill in the wet was there for everyone to notice. 1979 should have been his year as the Ferrari was the car to beat, but after retiring at Zolder, the title slowly slipped towards Scheckter who received the team’s support in the second half of the season. However, he still managed to win at Watkins Glen after setting an amazing time in the wet Friday practice, beating everyone by nine seconds.

The following year, Ferrari’s car was a mess, and at this time Villeneuve’s immense talent really started to shine. He did score only six points throughout the year, but his showings at Monaco, driving on slicks on a wet track, and Argentina completely shadowed those of Scheckter who retired come the end of the season. In 1981, paired with another disastrous car, the 126CK -- which only had a quarter of the downforce of the leading machinery -- he managed to win twice. At Monaco, he was 2.5 seconds quicker than Didier Pironi, but got beat by Piquet’s Brabham, but not even the Brazilian’s illegal car could stop Gilles from winning. Then, in Spain, he showed some superb defensive driving, leading a trail of five cars to the finish. Then, at that year’s Canadian GP, he finished on the podium in spite of the fact that his nose broke off and drove blind, in the wet, for a quarter of the race.

All of these hardships should have paid in 1982 in the form of a title for Gilles, but this never happened as he crashed at Zolder in qualifying in an attempt to beat Pironi’s time who had angered him after disobeying team orders at Imola. Sadly, nowadays most remember a wild Villeneuve, throwing his car around recklessly, but that is also due to the fact that for over half of his career he had to make due with terrible cars. In fact, tire engineers tell a completely different story: Gilles was incredibly gentle with the rubber, a talent revealed both at Long Beach and Kyalami in 1979 when he made the tires last more than anybody else, while team mate Schekcter shredded his set.

2. Michael Schumacher

Germany’s first World Champion is the most complete driver in F1’s history, acing all criteria one could think of. He was quick in the dry, masterful when the rain started to fall, brilliant in qualifying, and a workaholic when it came to setting the car up right. His pile of victories and seven world titles tell the story of the best driver of his generation and one of the best ever, but not the most talented or the cleanest.

The work ethic and maturity were apparent even from his early days in lower Formula, when Schumacher paid extra attention to setup, trying to understand every aspect that would lead him to a favorable outcome. He was cut from the same cloth like Senna and, similar to the Brazilian, he sometimes pushed the envelope and imposed himself using some questionable maneuvers. But not even his critics, who are all about his few antics, can deny his incredible skill seen especially -- like is the case with any all-time great -- when the car he was given was far from the best. His style, relying on a heavily front-end-biased setup that was deemed undriveable by team mate Eddie Irvine, was both quick and gentle on the tires and mechanics.

After pocketing two world titles with the Benetton he moved to Ferrari where he started working, along with other key personnel brought over from Benetton, to make Ferrari great again. His first win for the Scuderia came at the Spanish Grand Prix in 1996 in terrible conditions, Michael managing to hide all of the problems of the F310 to score the first of three wins that year. The following season, the team came up with a much more consistent machine, but was still 3rd best on the grid. Regardless, Schumi won five times and had a good chance for the title up until the last round at Jerez where his highly controversial clash with champion-to-be Jacques Villeneuve decided the victor – and it wasn’t Ferrari’s No. 1 driver.

This was one of the peaks of the German’s dark side, but this side came to light much less frequent than in Senna’s side. When the stars finally aligned, beginning in 2000, Schumi was unstoppable -- winning 5 titles in a row and beating most records that were in place the time. The rule change of 2005 meant Schumacher wasn’t a factor in the championship, but the veteran still finished a respectable 3rd. Then, in his final season with Ferrari, he again fought for the title until the very end, losing the 8th champion crown after his engine failed at Suzuka when he was out in the lead – a similarly frustrating story to that of 1998.

Proving that his fitness – which was always at the top of his priorities -- was still impeccable, he came back for a rather short and frustrating stint with Mercedes. Coupled again with Ross Brawn, the German team was on a learning curve while Schumi was on board, and thus did not achieve the expected results. Had the seven-time world champion stayed longer, maybe his list of wins and poles would have lengthened. As it happened, Michael retired at the end of 2012, but his legacy transcends time and he will be remembered for as long as motorsport will exist.

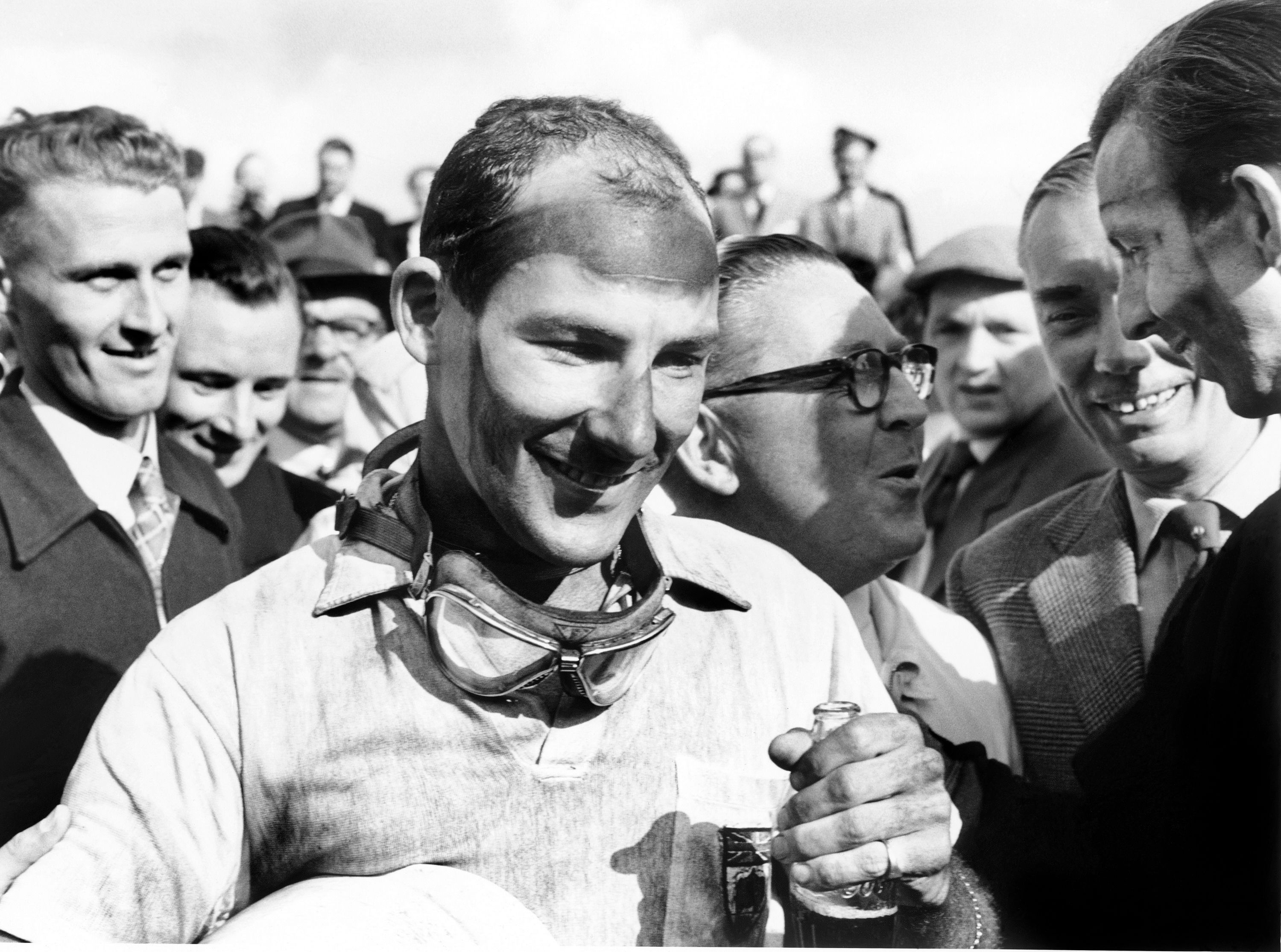

1. Jim Clark

It is peculiar how talent can hide in the most unassuming of places. James Clark Jr. was to become a farmer like his father, but a passion for motorsport, found while on boarding school, shifted his sights from cattle to cars. He soon found out that everything was extremely easy for him – winning again and again with no apparent fuss or effort. This carried on into his F1 days when Jim was still bewildered by the fact that the rest of the bunch cannot quite do what he’s regularly doing. Because what he was doing was, at times, purely impossible for anybody else as Jim hid inside him the biggest natural talent that the F1 world has ever seen – a talent that has not been matched since.

He appeared on F1’s radar in 1960 after Colin Chapman, Lotus team founder and designer, saw the talent in him after being beaten by Jim on track. The two soon formed a very close relationship, so close that Jim was never vocal about Chapman’s frail cars that were often very hard to drive at the limit. No, Jim just got in any car he was given and got the best of it – quick, without much setup work, regardless of weather, temperature or the track surface. He could drive anything as fast as it went – from the Lotus Cortina which he took to the BSCC crown, to the Lotus 19 sports car which he drove at the Nurburgring 1000km in 1961.

His record of just 25 victories may not seem impressive but the fact that he scored the most hat tricks in history, that is posting the quickest time in qualifying, the race, and leading all the laps on the way to finishing first is. Also, he’s won both his titles scoring the maximum amount of points possible, a feat that was achieved in the past by Ascari.

Jim also was immensely gentle with the car. For example, while Graham Hill needed a new set of brake discs for each session of an F1 weekend, Clark could carry on with a set for the whole weekend, being able to use that same set the following weekend as well. Also, he was able to nurse an ailing car home like no other and to hide the problems of any car in such a way that his mechanics could never tell if it was their improvements on the setup or Clark’s style that made the car go quicker. Talking about Clark’s qualities could go on and on, so I’ll just jump to mentioning some of Clark’s feats behind the wheel of his F1 Lotus cars.

At Monaco in 1963 he took pole by 0.7 seconds from Graham Hill, despite driving a car with a full fuel tank. After that, he proceeded to match Hill’s time with the older carbureted Lotus just for a goof. In 1966, he was on pole again at Monaco, this time driving the Lotus-BRM 43, which was nearly 100 horsepower down to Surtees’ Cooper that qualified 2nd. At Spa in ’63 in torrential rain he was on average half a minute quicker than anybody else in the second half of the race. At Milwaukee that same year, he lapped everyone but A.J. Foyt whom he respected greatly, in spite of the fact that he’d never been on that oval before. At Indy in 1965 he became the first man to win with a rear-engined car after leading 190 of the scheduled 200 laps, his margin of victory being roughly 120 seconds.

At the Nordschleife, he shattered the previous lap record by 17 seconds in qualifying, recording a 8:22:7. The following year, with the Lotus-BRM, he bettered his own record, managing a mind-boggling 8:16:5, which was almost two seconds quicker than Surtees’ best time. In 1967, at his last appearance on the Nordschleife, he posted an 8:04:1, which was 10 seconds quicker than the best Denny Hulme could do.

While I think these examples are about enough for anyone to start painting an image on Clark’s greatness, there are many more worth telling. He got back a lap at Monza in 1967 despite the fact that the race was run under dry conditions, and managed another superb drive at Spa in 1965 -- again through rain and fog, to claim his fourth win of the Belgian GP.

In his last year of racing, 1968, he stormed the Tasman Series, winning in the Lotus 49. He also won the first GP of that year, but he would take part in no other race as he perished in a strange accident at Hockenheim in an unimportant F2 event. The crash, which was caused by a broken rear suspension arm, cleared the way for Jackie Stewart to gain a place in the lime light. The Scot, who was a good friend of Clark’s, always maintained that Clark was "the driver’s driver", the man that could deliver the goods no matter what. So quick, versatile and gentle that even Senna appointed him as the best ever.