The Aston Martin DB3S is a special car although it may have been overshadowed as years came and went by a certain finned Jaguar and the DBR1/300 that won at La Sarthe for David Brown's marque. However, its status as a bit of a giant killer and the fact that the boys in Feltham kept using it for four seasons in international competitions puts the DB3S in a unique spot in Jaguar's racing history. This car, chassis #2, is one of only 11 works cars ever built and it won the Goodwood Nine Hours ahead of the D-Type and Ferrari's 750 Monza. It is, then, no wonder that RM/Sotheby's hoped it would sell for anywhere between $8.75 and $10 million when it crossed the block last Thursday during the Monterey Car Week. Well, it didn't but you can't deny this is one rare, gorgeous, and expensive product of the '50s. Need further proof? A copy of the definitive book on this car sold 14 years ago for some $1,500.

When you talk '50s sports cars, your mind slaloms between William Haynes' C-Type and D-Type, together amassing five overall 24 Hours of Le Mans wins, the classic 250 Testa Rossa, the dominant but also infamous 300 SLR, and also the Lister Knobbly and Maserati's 300S. Aston Martin isn't among the names on the tip of your tongue despite it racking up quite an impressive number of wins between 1953 and 1959 with the DB3S and the DBR1 respectively. That's because the Aston Martins were always seen as underdogs, always seen as members of the pack, those that'll play second fiddle to the big fish when, in fact, it wasn't like that at all. David Brown employed some of the best engineers and drivers at the time and his cars were some of the best. Yes, most often down on power, yes, most often with an Achilles' heel (cough, the DBR1's gearbox and ergonomics) but they were good cars. And now we'll talk about the first one of those, the DB3S, offspring of the DB3 and a car that's getting a bad rep for being actually friendly on the road.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works

- Make: Array

- Model: 1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works

- Engine/Motor: inline-6

- Horsepower: 225 @ 6000

- [do not use] Vehicle Model: Array

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Exterior

Basically, the entirety of the car's nose is modeled to follow the classic shape of the grille, one that was first seen on the Aston Martin Atom prototype of 1939. On the Atom, the grille wasn't the result of a designer trying to make something out of an oval grille and coming up with this lopsided shape. In fact, the broader median section came about simply because the Atom featured a radiator in the middle with the two smaller sections of the grille on either side there to feed air into the front brake ducts. The shaped evolved when the DB2 came about after David Brown purchased the company post-WW2 and, on the DB3S, the shape of the grille is simpler, without a visible hump as the line at the top dwindles almost straight down to create a teardrop-esque shape. The shape of the main inlet would evolve further when the DBR1 appeared as that one featured a near oval opening with an egg-crate-like grille to cover it. It's worth mentioning also that the shape of the inlet on the DB3S evolved as years went by.

Originally, the top bit extended further up the nose thus having a shape reminiscent of the original DB3 and the DB2 (as well as sporting the traditional egg-crate mesh) and it kept evolving until it looked like an oval on its side, with only the outline suggestive of the old, lopsided shape. By that time, in 1957, the DBR1 was almost ready and Aston Martin fitted the few DB3S still run by the factory with more aerodynamic headlights with clear covers that matched the shape of the fenders.

The top bit of the nose is accentuated by two creases that essentially follow the line of the grille and then continue backwards before they blend into the bodywork along the contour of the hood. Inboard, on either side of the tall headlights that sprout from the curved front fenders (with a crease at the top that cuts through the air), the nose is carved in and almost flattened. That's where you'll find the registration decal - UDV 609. The indicators are placed to the left and to the right of the lower edges of the main inlet, with the tow hook below the nose.

The car's profile is as much elegant as it is functional. The 'scoop-sided' appearance fills double duty: it takes air out of the engine compartment and makes way for the exhaust pipes to come straight out. The pipes go down along the edge of the car before ending just below the doors. The line of the doors is a bit lower than that of both the front and the rear fenders, all coming together via one swooping line from one tip of the car to the other. The rear fenders are longer and more straight-cut on this example compared to others that feature a rounder, shorter tail section similar to that of the DBR1.

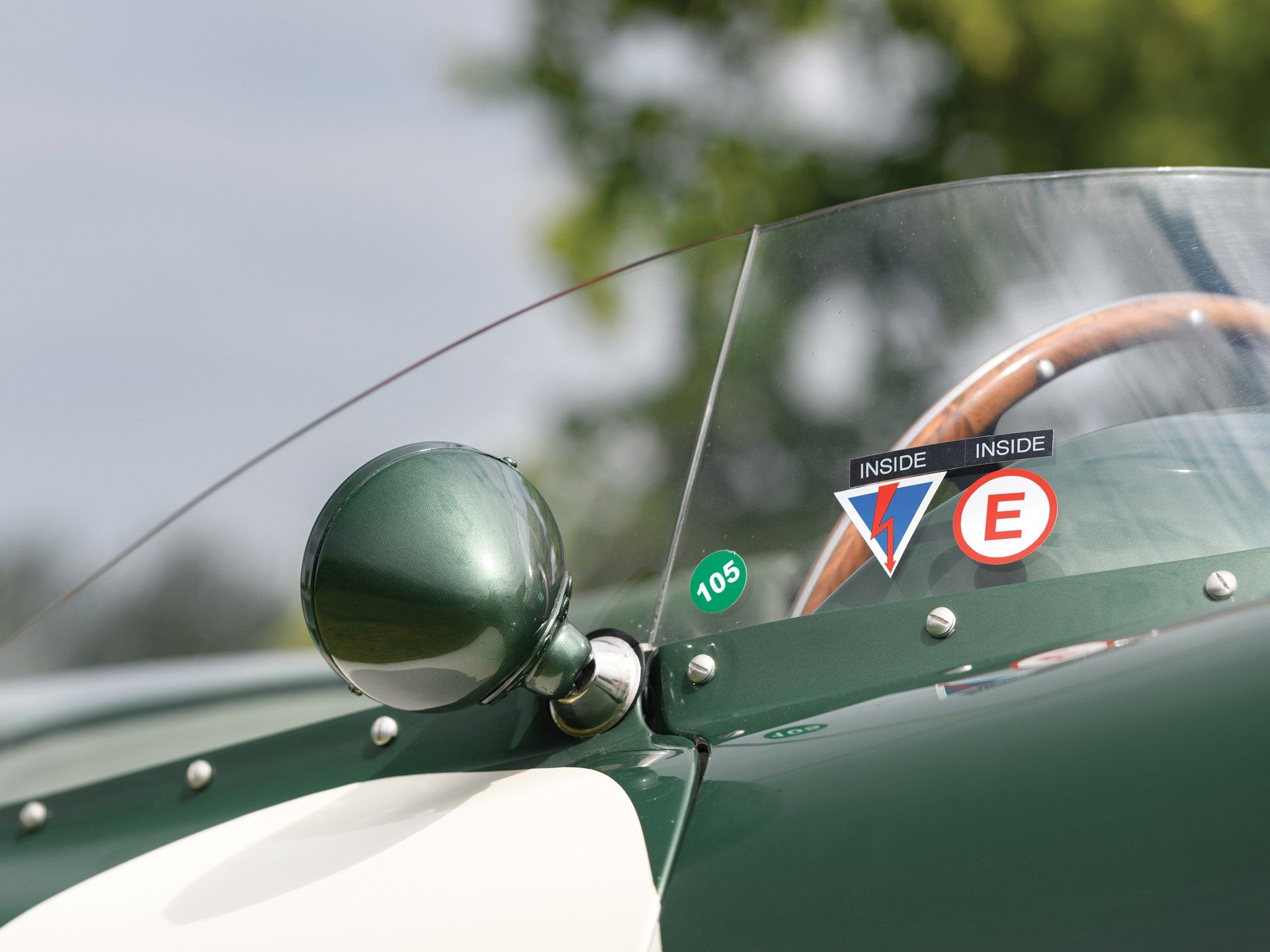

The lightweight multi-spoke Borrani rims with chromed knock-offs don't even try to hide the jumbo-sized drilled discs behind them. The DB3S runs on Dunlop Racing rubber developed specifically for historic racing cars. The rounded air deflector in front of the driver's compartment is bolted onto the body and the exterior rear-view mirror placed on the door is actually painted in British Racing Green just like the rest of the bodywork.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works exterior dimensions

|

Length |

153.7 in |

|---|---|

|

Width |

58.7 in |

|

Height |

41.5 in |

|

Wheelbase |

87 in |

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Interior

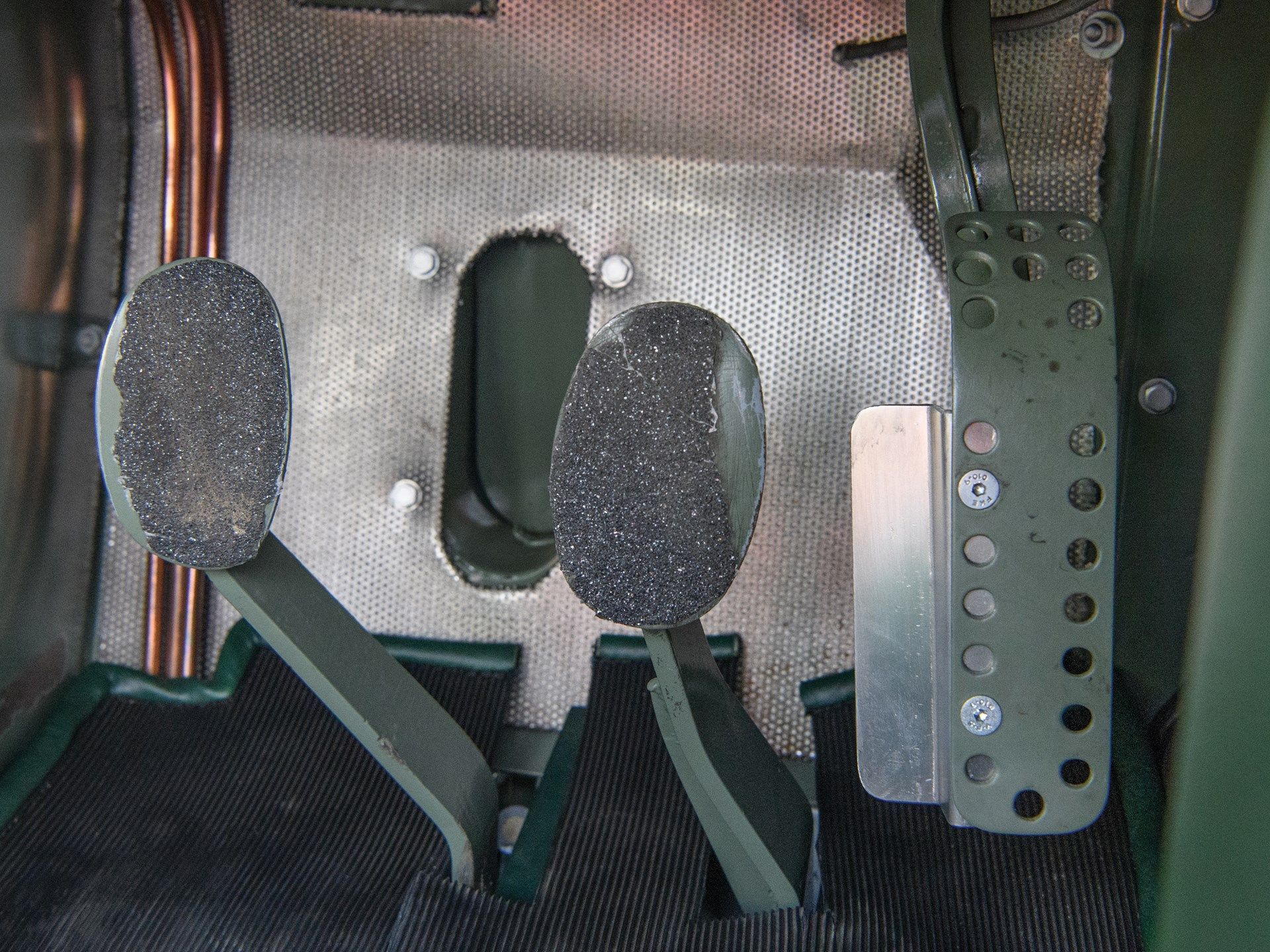

The interior of the DB3S is exceptionally small and you'll find yourself crowded by the transmission tunnel on one side and by the door on the other. However, getting in and out isn't that hard because, after all, this is a roofless sports car. The downsides of easy access become evident when you roll over with this hoop-free example that's nothing short of a neck-breaker in that situation. Still, this is how it raced back in the '50s and this is how it looks best, without a roll hoop to ruin its lines.

Pressure and temperature gauges - all from Smiths - for the water and oil are all there with the ignition button to the right next to the start button. On either side of the tachometer, there are other knobs and further to the driver's left including an odometer hanging from the lower edge of the dash on an added piece of metal. Of course, there's nothing fancy in the footwell either with the gas and the clutch pedals both connected through the floor and only the gas pedal hanging from above. The tall shifter comes straight out of the bulging transmission tunnel and ends with a black, round knob.

The passenger's seat is shaped so that you, the driver, have room to shift in the lower gears. In the passenger's footwell, you'll find the battery (which is why it's better to keep the tonneau cover on and accept the fate of a loner, albeit one that owns a DB3S) and a fire extinguisher. In the back, between the seats, there's some leather covering and a pouch.

Motor Sport Magazine's then-Deputy Editor drove the DB3S in 1978 and reported that "the driving position is straight-armed, though the seat is upright with a tendency to slide its occupant towards the pedals." The tester goes on to report that the David Brown four-speed (with a ZF limited-slip diff) was slick to operate, bettering Jaguar's units at the time. The ride is still rough but not as rough as with other '50s sports racers as the DB3S is easy to maneuver on the road although the brakes hardly bite if you don't drive it hard, while the steering is rather light while still being precise.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Drivetrain

The DB3S isn't ground-breaking under the skin but it needn't be to win races and remain competitive for four years - it won 15 times in international events alone, by the way.

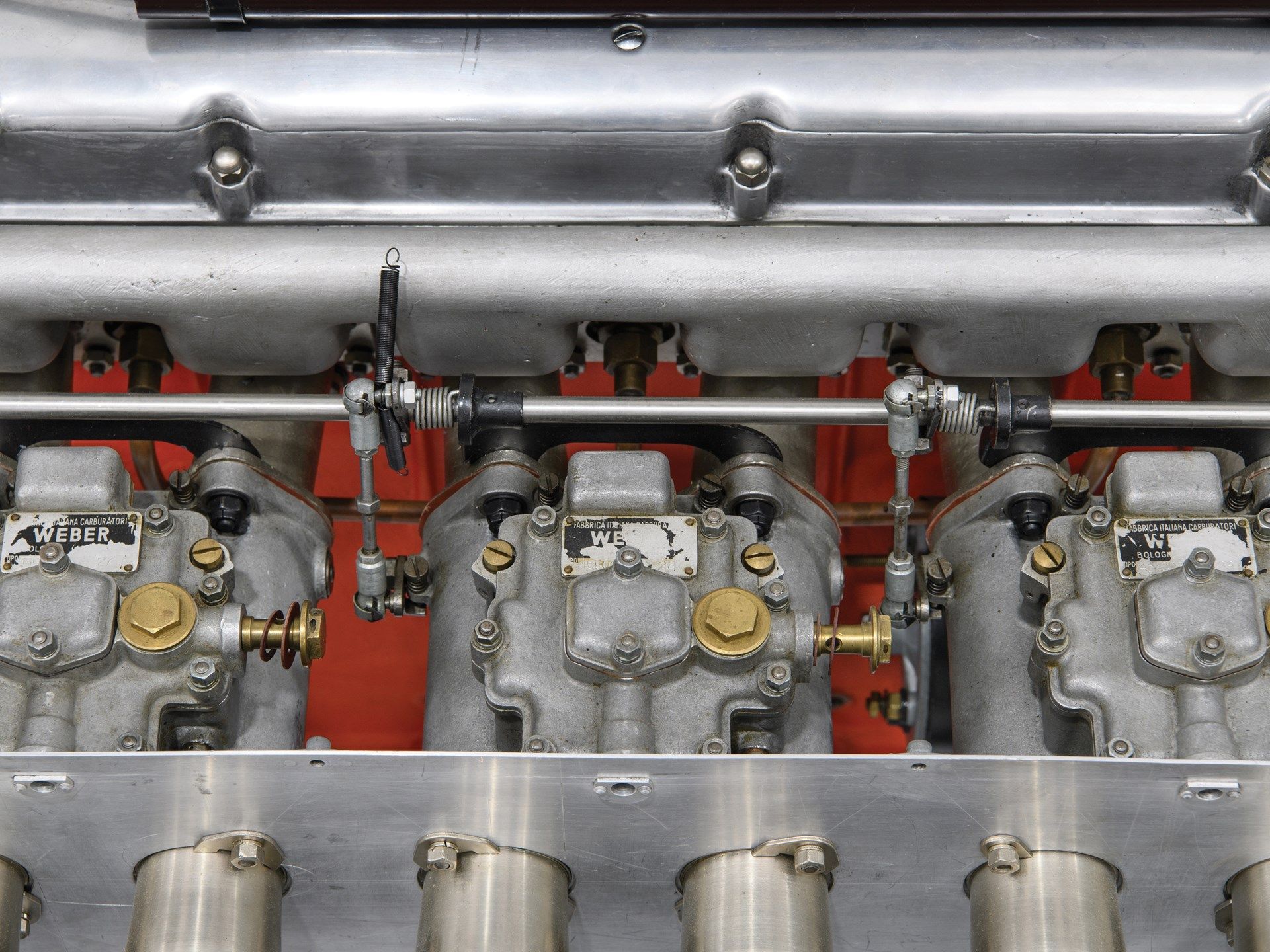

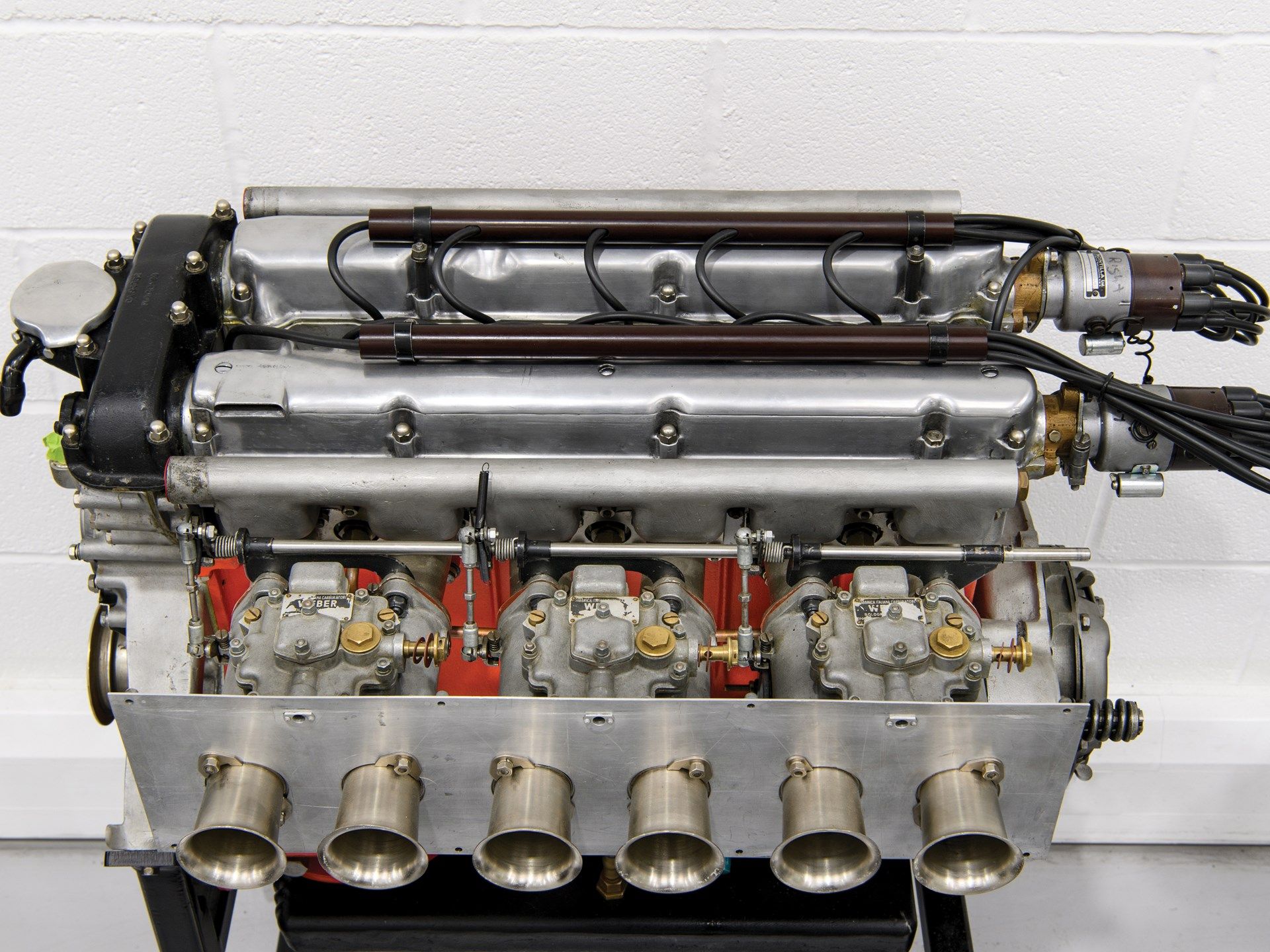

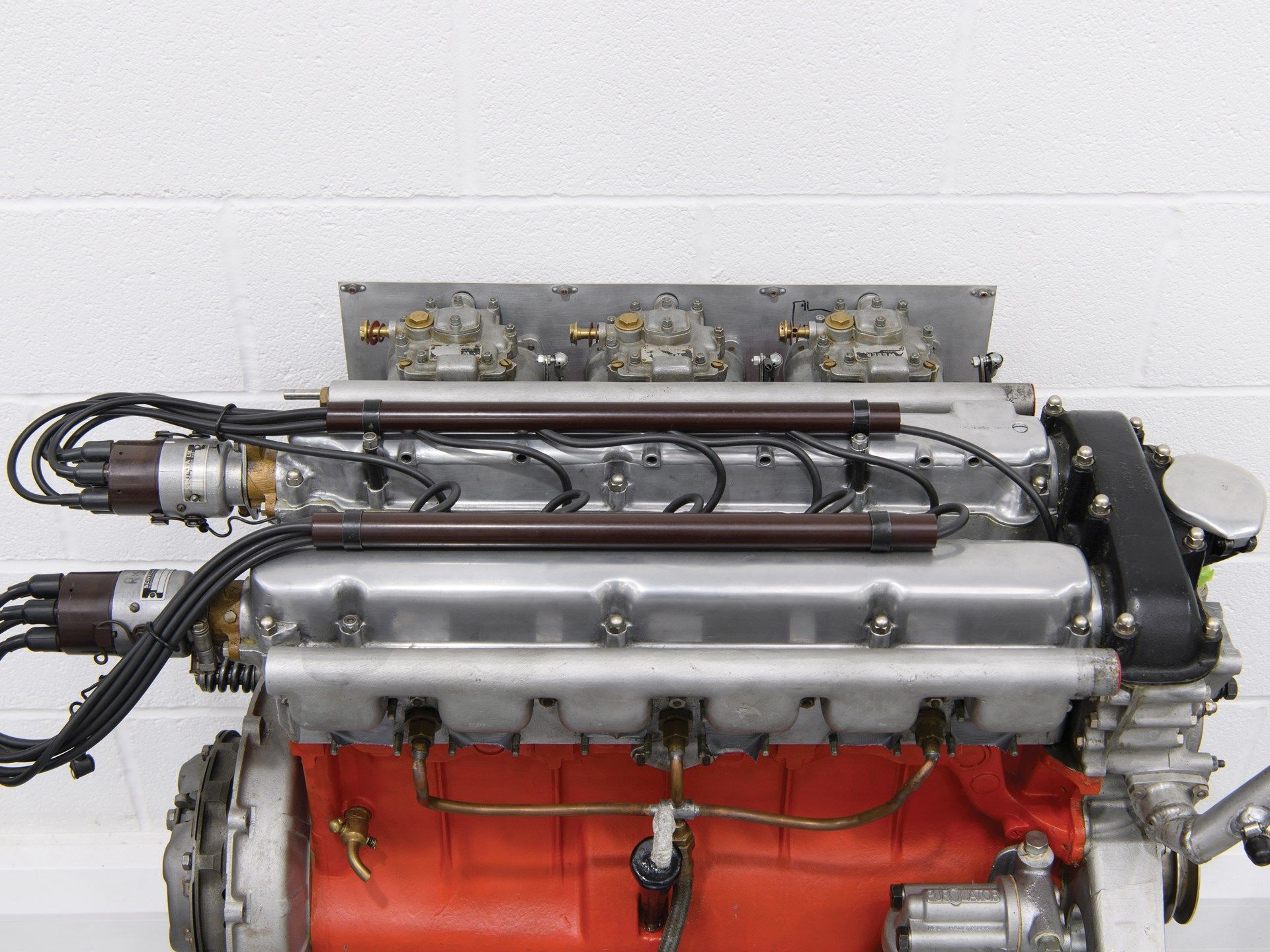

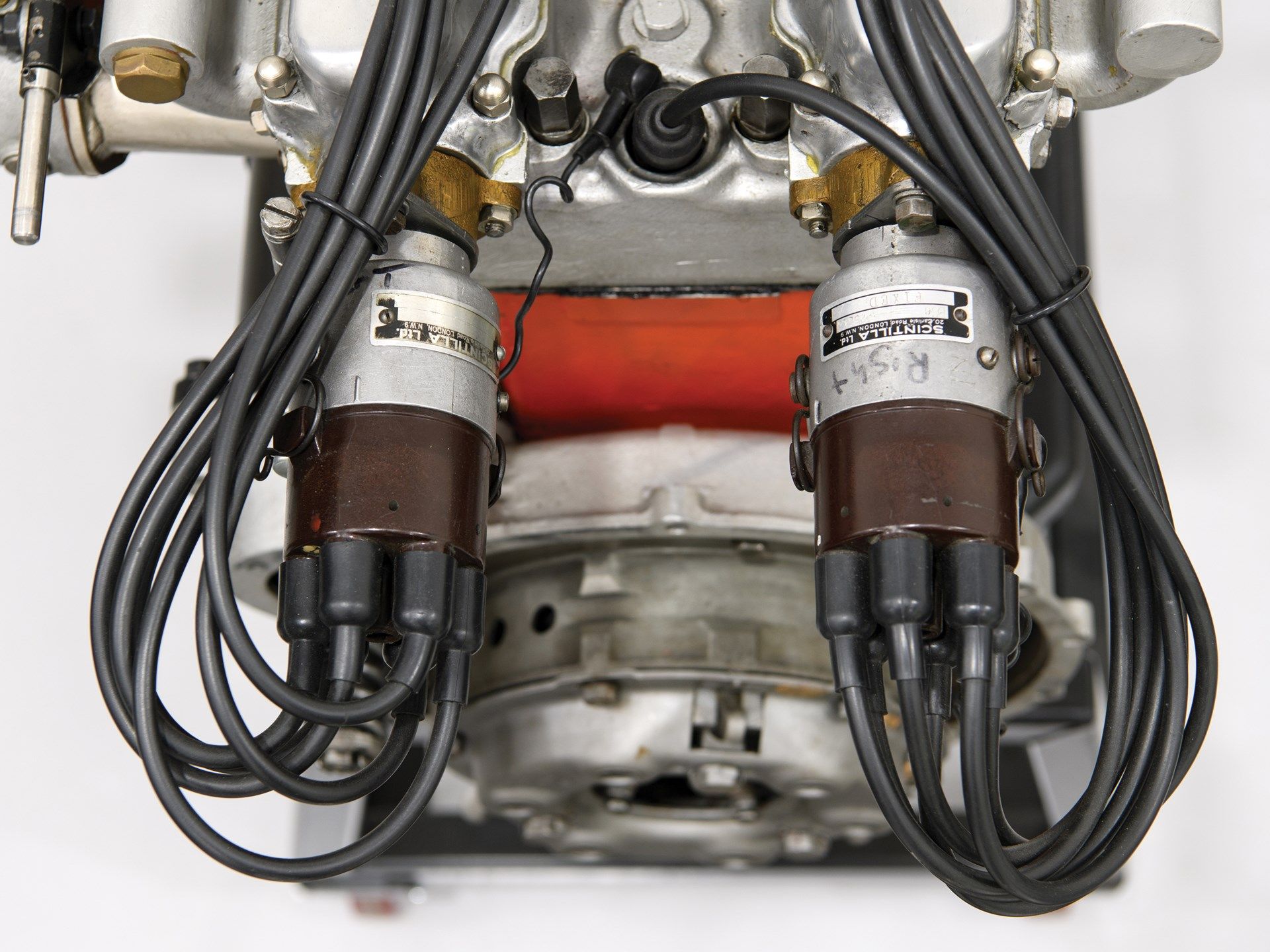

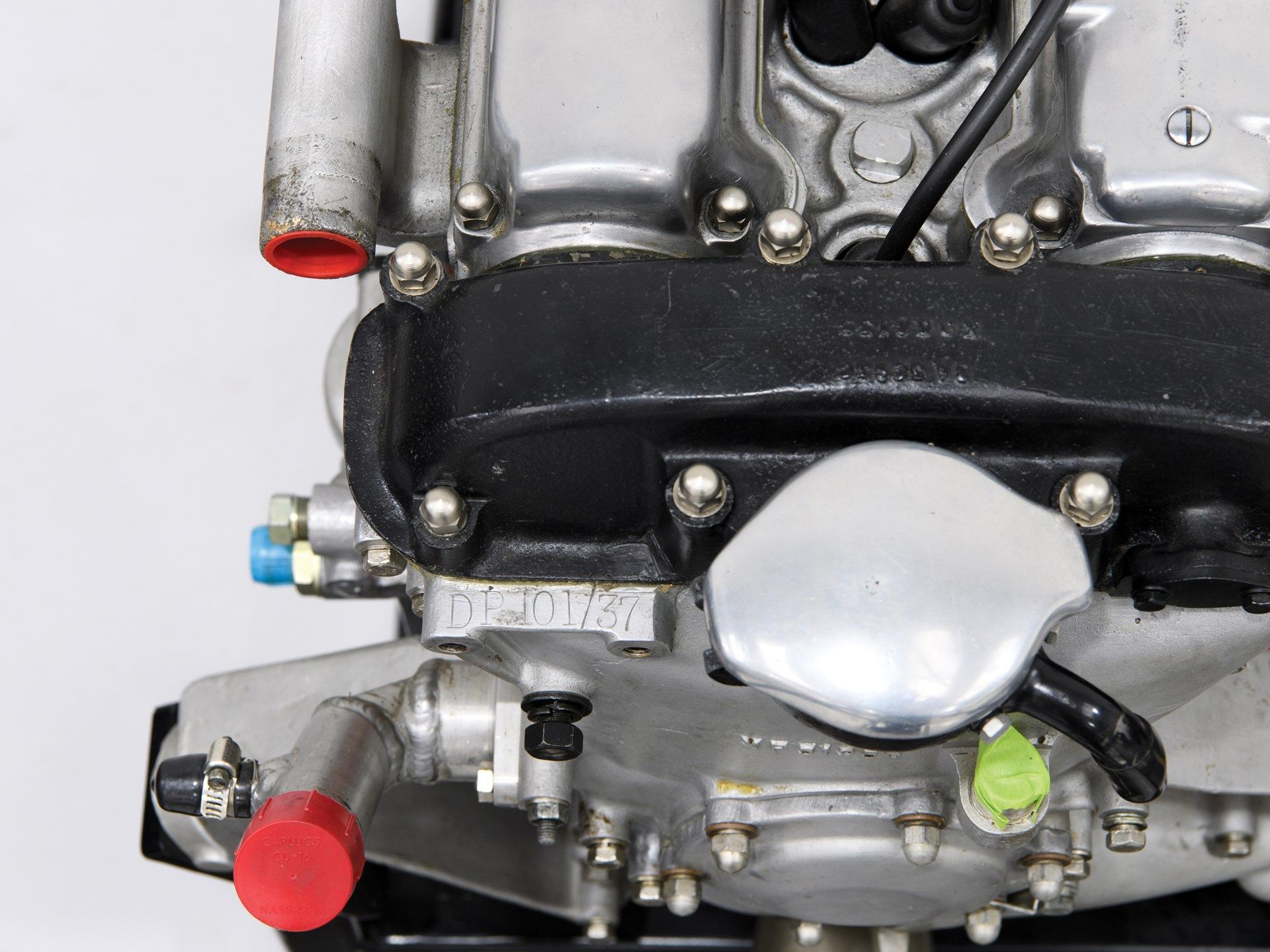

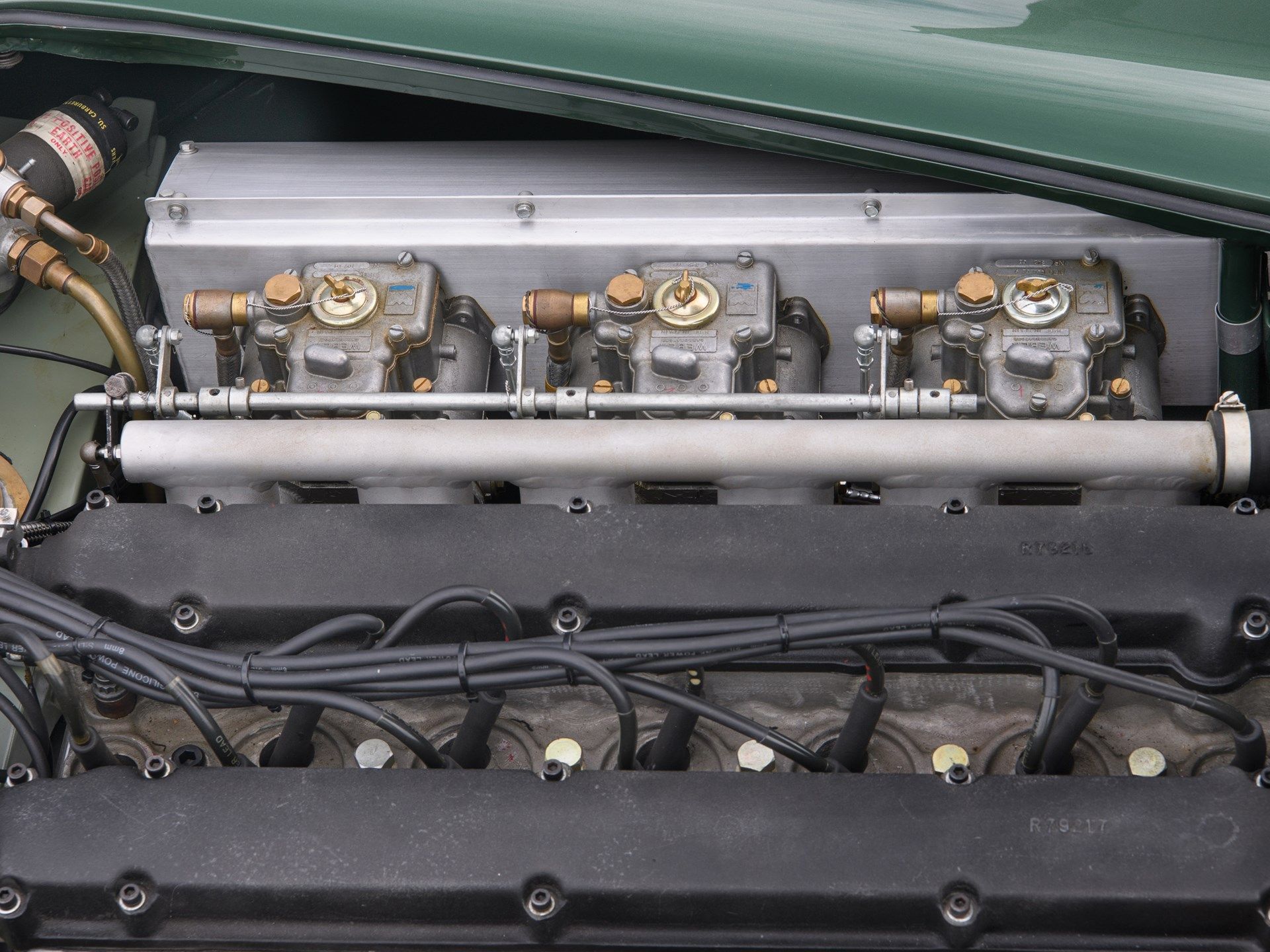

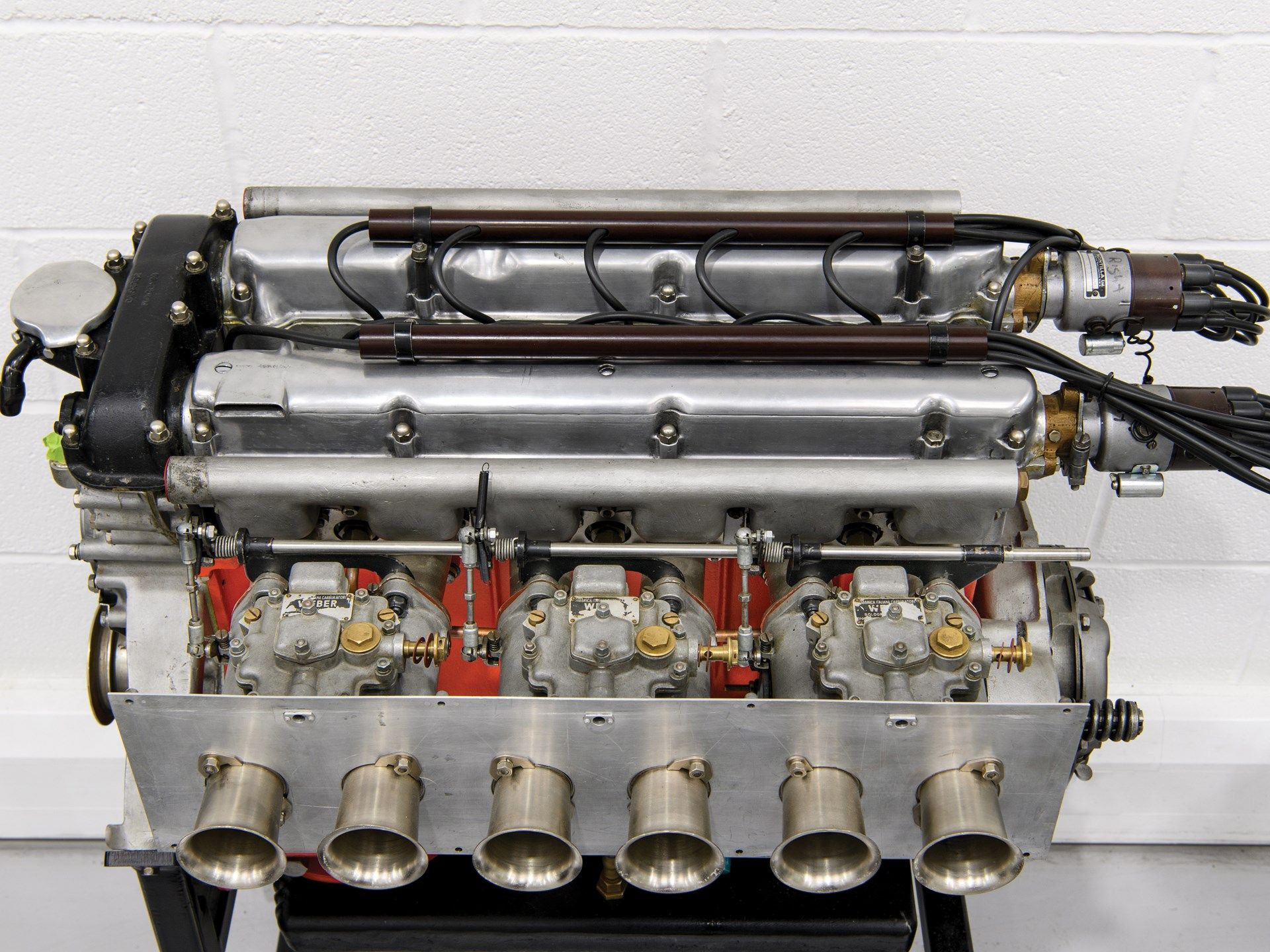

The engine is the Lagonda DP101 straight-six, the 3.0-liter version of W.O. Bentley's famous inline six-banger designed for Aston Martin after the War. This powerplant, with a cast-iron block, steel crankshaft, and aluminum heads, featured dual-overhead cams, two valves per cylinder, and was watercooled. Max output in Works configuration was somewhere between 230 and 240 horsepower at 6,000 rpm (with a compression ratio of 8.68:1). To put it into perspective, the 20 customer chassis built were about 40 horsepower down on power when compared to the works cars (chassis #1 through #11, although #11 was never raced in period). The engine was fed by a trifecta of Weber carbs (Solex carburetors were fitted to some cars too) and sported wet-sump lubrication.

Still, as Brooks points out, "It was lovely to drive: strong, balanced and competitive on circuits where power was not a priority." While the original DB3 came with a five-speed transmission, Aston Martin reverted to a David Brown four-speed manual with the DB3S, sending power through an LSD down to the rear wheels. Originally, drums were in charge of stopping power (inboard drums in the back) but, from '55 onward, Girling discs took over.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works

|

Engine: |

Lagonda DP101 naturally aspirated, DOHC, 12-valve, water-cooled 3.0-liter (2,992 cmc) straight-six |

|---|---|

|

Bore x stroke: |

3.3 x 3.5 in |

|

Compression ratio: |

8.68:1 |

|

Output: |

230 horsepower at 6,000 rpm |

|

Lubrication: |

Wet sump |

|

Ignition: |

Twin spark |

|

Fuel feed: |

Triple Weber 45 DCO carburetors |

|

Suspension: |

trailing links, transverse torsion bars, anti-roll bar, with piston-type shock absorbers in the front and DeDion axle, trailing links, transverse torsion bars, anti-roll bar, with piston shock absorbers in the back |

|

Brakes: |

Girling ventilated discs all around |

|

Gearbox: |

David Brown four-speed manual with LSD |

|

Steering: |

Unassisted rack-and-pinion |

|

Performance: |

0-62 mph in 6.5 seconds |

|

Top speed: |

in excess of 145 mph (depending on gearing) |

|

Weight: |

2,156 pounds |

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Prices

The DB3S is a rare car, as you'd expect coming from a boutique manufacturer (at least it was at the time!) that had barely introduced its first bona fide sports racing car in 1952.

While rare and, as such, desirable, the DB3S didn't win any world championship (the DBR1 did, but at a time when the competition was weaker than when the DB3S was in its prime) nor did it conquer the 24 Hours of Le Mans (the fact that it came second three times in four years only entertains us automotive geeks), so prices are inconsistent.

In 2012, RM/Sotheby's sold one at Monterey for $3.68 million while two years later, in 2014, another chassis was sold through Gooding & Co. at Pebble Beach for $5.5 million. Most recently, in 2016, at the Bonhams Aston Martin Works sale in Newport Pagnell (at the Aston Martin HQ), chassis #5 didn't sell with pre-sale estimates putting it in the $7.3-8.5 million ballpark.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Racing History

Chris Nixon, one of the most revered authors of motorsport-related books, wrote in the definitive book on the DB3S that "in four seasons as a front-line, factory racer, the DB3S started 35 major races and scored 15 outright wins, 13 seconds and 7 thirds." As Nixon only mentions the 'major' ones, he doesn't add the plethora of national successes, both in the U.K. and elsewhere. And you should also not forget that the DB3S was underpowered and running in a lower class - the engine capacity for sports cars in international racing was only capped at 3.0-liters at the end of 1957. Before that, you could race 5.0-liter behemoths if you wished and the DB3S would always play second-fiddle to those big boys on fast tracks but it still racked up class wins as there weren't too many (other) 3.0-liter sports cars in '53-'55 besides Maserati's 300S.

John Wyer, Aston Martin team boss at the time, said this was due to the fact that "we tried to do far too much with far too little." He obviously talked about a lack of funds. While Brown wanted the world, he didn't have the cash to go and grab it and his efforts fell short off greatness. At Le Mans, for instance, four DB3Ss were brought (two with supposedly aerodynamic FHC bodywork that proved disastrous) as well as a V-12 engined Lagonda. None of them survived and the only highlight that year was a third-place finish the Buenos Aires race for Collins/Thompson. Collins, coincidentally, would become the custodian of DB3S/2 when the car wasn't recalled by the factory to be entered as a Works car.

DBS3/2 ran a number of important races in 1954 including the Buenos Aires round of the world championship (where it did not finish), the Sebring 12 Hours (where it did not finish), and the Mille Miglia (where Reg Parnell crashed it hard enough to require a full-blown reconstruction back at base where a new chassis was fitted but the serial number kept). Four out of the 10 works DB3Ss were recipients of new chassis or bodywork during their lifetime. Back at the races, Collins and Pat Griffith recorded another DNF in the RAC Tourist Trophy (that the DB3S had won in '53) when the differential gave out as Collins was battling with Hawthorn's Ferrari and a pair of factory-entered Lancias wheeled by Fangio and Ascari.

In '55, Aston Martin sold chassis #2 on to Peter Collins who registered it as UDV 609, the registration plate it still sports to this day. The car raced that year mostly in British sports car races although it did compete in the Swedish GP at Kristianstad where it retired.

Tom Kyffin bought DB3S/2 in 1956 as Collins moved on to greater things at Ferrari. Kyffin racked in a couple of national-level wins before selling it to John Dalton who, in turn, sold it to Roy Bloxam. George Gale was the car's fifth owner and he kept it for about two decades, in this time outfitting it with a passenger door and a cigarette lighter inside to make it a bit more road-worthy. Later on, it was returned to full Works specification as raced by Collins & Co. in 1955.

1953 Aston Martin DB3S Works Competition

1954 Jaguar D-Type

The Jaguar D-Type is arguably the most famous racing car of its type stemming from that era. While its eye-catching tail that extended aft of the driver's seat to cut through the air wasn't really a first on sports cars, the overall design proved poignant enough to stand the test of time. This is also because of the D-Type's thick record of on-track successes. It won three times on the trot at Le Mans, albeit only once in the hands of the factory and that one time due to the withdrawal of the far superior Mercedes-Benz team, but victories in almost all of the marquee events of the '50s make it a legend among legends.

As the follow-up act to the well-regarded C-Type, the D-Type managed to raise the bar even further. William Heynes designed a revolutionary semi-monocoque chassis comprising of aluminum alloy sheets with an aluminum sub-frame in the front to cradle the engine while the tank (in fact, a deformable fuel bag) and rear suspension assembly were bolted onto the rear bulkhead. Malcolm Sayer was the man responsible for the looks, using experience gathered while working with the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

Unlike the DB3S, Heynes employed dry-sump lubrication in the D-Type to reduce the height of the 3.4-liter (later 3.8-liter) straight-six that put out 250 horsepower early on and would crank out over 265 by the end of its competitive tenure. The D-Type debuted with disc brakes in 1954 which helped it stand out among its drum-equipped peers. At Le Mans in '54, the D-Type reached 172 mph without the long nose fitted in '55 - about 12 mph above what the 375 Plus driven to victory by Gonzalez/Trintignant managed. The D-Type's reign came to an end in 1958 when the engine size was limited to 3.0-liters. While Jaguar did develop a 3.0-liter version of its straight-six engine, it proved oftentimes unreliable and Jaguar never returned to its winning ways although other Jaguar-powered cars did (like the Lister-Jaguar with Costin bodywork).

Read our full review on the 1954 Jaguar D-Type

1955 Maserati 300S

In their heyday, the Jaguar D-Type and the DB3S would race against one another in both international and national-level races although they weren't put in the same class all the time. That's because the D-Type ran between '54-'57 with a bigger engine. However, one car that did fight the DB3S with similar firepower was the 300S, Officine Alfieri Maserati's way to bridge the gap between the small 200S and the leviathan that was the 450S. The 300S debuted in 1955 when its straight-six engine developed from the block of the 250F put out 245 horsepower.

It featured a trellis chassis structure that supported the Fantuzzi-made aluminum body. While both the suspension and the brakes were almost identical to what came on the 250F, the 300S did feature a DeDion rear axle (like the DB3S) and a transverse-mounted four-speed gearbox with two chain-driven camshafts. The car's first year in competition was tough as the car was plagued with poor reliability.

However, by 1956, most problems were fixed - although Guido Alfieri never managed to make fuel injection work and the car stuck with triple Webers throughout its life - and it won that year's Nurburgring 1,000-kilometer race shared by the entirety of Maserati's panel of works drivers: Piero Taruffi, Harry Schell, Jean Behra, and Stirling Moss. It won against Ferrari's 860 Monza and 290 MM (both running 3.5-liter units) as well as D-Types and Aston Martins. A 300S also finished second overall and first in class in the 1957 12 Hours of Sebring. After Guidizzolo's accident that same year, the factory greatly reduced its involvement in sports car racing although the 300S kept on winning at a national level in the hands of a number of privateers.

Read our full review on the 1955 Maserati 300S

Conclusion

The Aston Martin DB3S is the car that really placed the foundation stone for the DBR1's success story. It was the car that firmly put the British automaker on the map as a serious contender in international sports car racing at a time when Ferrari and Jaguar were at the top of the pile helped by much heftier engines. Aston Martin succeeded thanks to a car that was lithe and maneuverable, although top-end speed was never something to write home about. Most if not all of its drivers spoke at great length about how well it drove and how manageable it was in slick conditions.

With 15 international wins under its belt, the DB3S certainly doesn't deserve the reputation it's got as 'just one of Aston Martin's early sports cars'. Instead, it should be noted as the one with the longest career and a string of important wins on some of the world's best-well-known tracks, a car without which Aston Martin would've never conquered the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Out of the 11 chassis built to be used by the factory, chassis #2 doesn't quite have the most enviable record - it's not one of the cars that finished runner-up at Le Mans - but it did win on a number of occasions too and was driven by some drivers that are many people's idols nowadays. While this would be enough for it to find an owner on the spot, it seems like this wasn't the case during RM/Sotheby's 2019 Monterey sale but this doesn't mean the car isn't extremely valuable or sought after. It just means that the right person wasn't there in the room (or on the phone/internet) that night to get it. What we know for a fact is that if we had a large enough garage and if money was no object, DB3S/2 would've been a welcomed addition to our collection as a key part of Aston Martin's heritage.

Further reading

Read our full review on the 1956 Aston Martin DBR1

Read our full review on the 1963 Aston Martin DP215

Read our full review on the 2018 Aston Martin DBS 59