The 24 Hours of Le Mans is one of the most grueling tests for both man and machine in the whole of the racing world.

Organized each year around the scenic country roads near Le Mans, the race's long history is an undying resource of amazing stories and today we're looking back at some of the most amazing moments we celebrate this year such as the 30th anniversary of Jaguar's last outright win or the 50th anniversary of Porsche's first. 2020 also marks the 40th anniversary of Rondeau's one and only win by a man driving a car bearing his own name.

Awesome things always seemed to happen at the beginning of a decade

From somewhat humble beginnings as a race organized to test vehicle durability and an avenue for manufacturers to display their technical prowess on the track for customers to see, the 24 Hours of Le Mans grew exponentially over the decades to become the centerpiece of not only the World Endurance Championship, the FIA's premier endurance racing series, but also the entirety of the endurance racing world alongside such events as the 24 Hours of Daytona, the 24 Hours of the Nurburgring or the 24 Hours of Spa-Francorchamps.

We all remember - if not first hand, from movies and documentaries - the so-called Ferrari era in the early '60s when the Prancing Horse from Maranello scored six overall victories on the trot or the glorious Group C days in the '80s or the LMP1 battles of a few years ago between two of the automotive world's biggest juggernauts: the VAG Group represented by both Porsche and Audi, and Toyota.

This time, we're looking back at events that happened in the years that end with a '0' and we'll take down memory lane from the golden (but very, very dangerous) days of the '50s and '70s all the way to the 2000s and up until the present day when we had a virtual 24-hour race replace the real race due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1950 - The year of titanic one-man stints

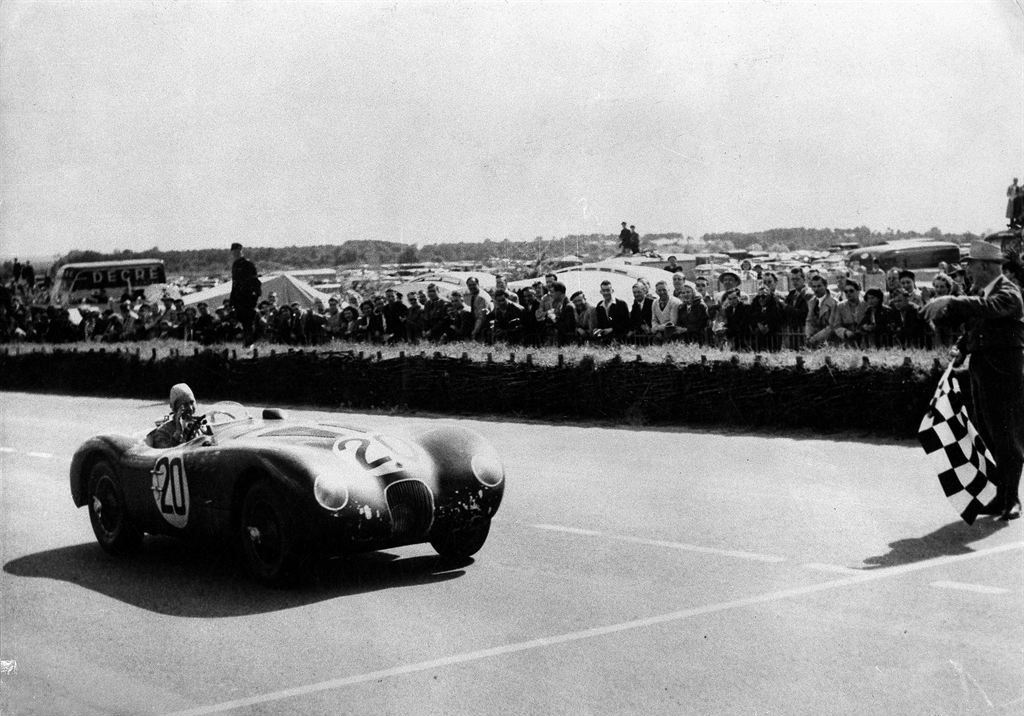

The roar of the engines once again returned to the La Sarthe valley in 1949 for the first post-WW2 edition of the 24-hour race. Ferrari ended up on the top of the rostrum come Sunday afternoon with Luigi Chinetti Sr., the future American Ferrari importer and a close friend of Enzo Ferrari's, doing the lion's share of the work aboard the Ferrari 166 MM he shared with Lord Selsdon.

In a time before strictly enforced minimum and maximum drive times, such iron-man stints were possible, also because the average speeds were a lot slower than what they are today. Chinetti's record-breaking drive was bettered one year later by both Eddie Hall and Louis Rosier.

Before we delve into the details of Hall's and Rosier's monster drives, let's just remember that, nowadays, no driver can drive for more than four hours in a six-hour period, nor drive more than 14 hours out of the whole 24. With that in mind, take into account that Louis Rosier, who was 44 years old in 1950, drove all but a handful of laps in a Talbot-Lago TS26 GS in the race.

Rosier, a veteran Grand Prix driver, entered the 1950 edition of the race alongside his son, Jean-Louis, driving a tried and tested Talbot-Lago, a sports car effectively based off of Tony Lago's TS26 F1 contender albeit with cycle fenders over the tires, a minuscule windscreen, mudguards, a bigger fuel tank and drum brakes, and a passenger seat. Rosier Sr. took the start but was forced back into the pits in the early stages after a rocker arm in the valve train had been bent by a downshift from fifth to second.

Former Bugatti mechanic Robert Aumaitre, who was stationed at Rosier's pit, had to distract the ACO officials as he ran back to the camper to get a replacement rocker arm as the operation wasn't allowed under the AIACR's regulations back then. Helped by Talbot drivers’ wives who encouraged ACO's men to indulge in a glass of champagne in the meantime, Aumaitre managed to grab hold of a rocker arm and apparently conceal it under the buns of an oversized sandwich. He then set out to work swapping out the broken part for the new one which took an agonizing 45 minutes but all that mattered was that Rosier was back in the race chasing Ferrari's horde of roadsters. This time, however, it was Jean-Louis who was in the driver's seat but the young man didn't linger too long at the controls of the Talbot as his father soon took over after replenishing his energy courtesy of some bananas.

By the end of the fourth hour, Rosier Sr. had been running second but the mechanical troubles set him back and, unwilling to relinquish the wheel and allow his son to take over anymore, the aging Louis pressed on and obliterated the 1939 lap record by 20 seconds, thus posting the first 100-mph lap around Circuit de la Sarthe.

Nobody could match veteran Rosier's pace and before long he was back in the lead, a lead he'd never let go of - despite at one point during the night being struck by an owl in the face.

It's considered that Rosier the father drove anywhere between 22 hours and 23 hours and 40 minutes on his own (period reports conflict one another when it comes to stating precisely how much Rosier Sr. drove but all agree that Jean-Louis was behind the wheel for no more than a pair of stints with some sources even claiming the youngster only completed three laps).

During that same race, Britain's pride was defended by a number of open-top Jaguars, as well as some fixed-head Aston Martins but none looked more peculiar than Eddie Hall's Bentley Corniche powered by a 4-and-1/4-liter engine. The car, a pre-War specimen bought by Hall back in 1933, had seen plenty of racing action throughout the '30s after Hall was able to persuade Bentley, then owned by Rolls Royce, to support his racing exploits. With factory assistance, Hall was a force to be reckoned with in the Tourist Trophy scoring a trifecta of second-place finishes between 1934 and 1936 despite being arguably the fastest guy out there.

The Corniche was also on the entry list of the 1936 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans but the race was canceled due to the tough economical situation in France and growing social unrest. Undeterred, 14 years down the road Hall had another go at racing his Bentley at Le Mans, only this time it was decidedly the oldest car in the field, its aerodynamic Offord & Sons coupe body unable to conceal the fact that it was a product of the Interwar period.

Making a gargantuan effort, he also never stepped out of the car to let team-mate Tom Clarke to have a go despite him being always at the ready. Instead, Hall drove 2,000 miles or 236 laps on his own to come home eighth overall. He's one of only two people to have ever driven the 24 Hours of Le Mans solo and, after the race, when inquired by Motor Sport Magazine's Denis Jenkinson of his physiological needs during the relentless drive, Hall simply replied "Green overalls, old boy!"

1970 - Porsche finally wins it

The duo of Hans Herrmann and Gerrard Larrousse was beaten by John Wyer's Jacky Ickx and Jackie Oliver who'd driven a masterful race in the old Ford GT40 Mk. I to take the Blue Oval's fourth win in a row at La Sarthe. But, with Ford finally out of the picture and Ferrari scrambling to build a five-liter sports car after putting its money on a three-liter contender in '69, Porsche seemed to be destined for victory in 1970.

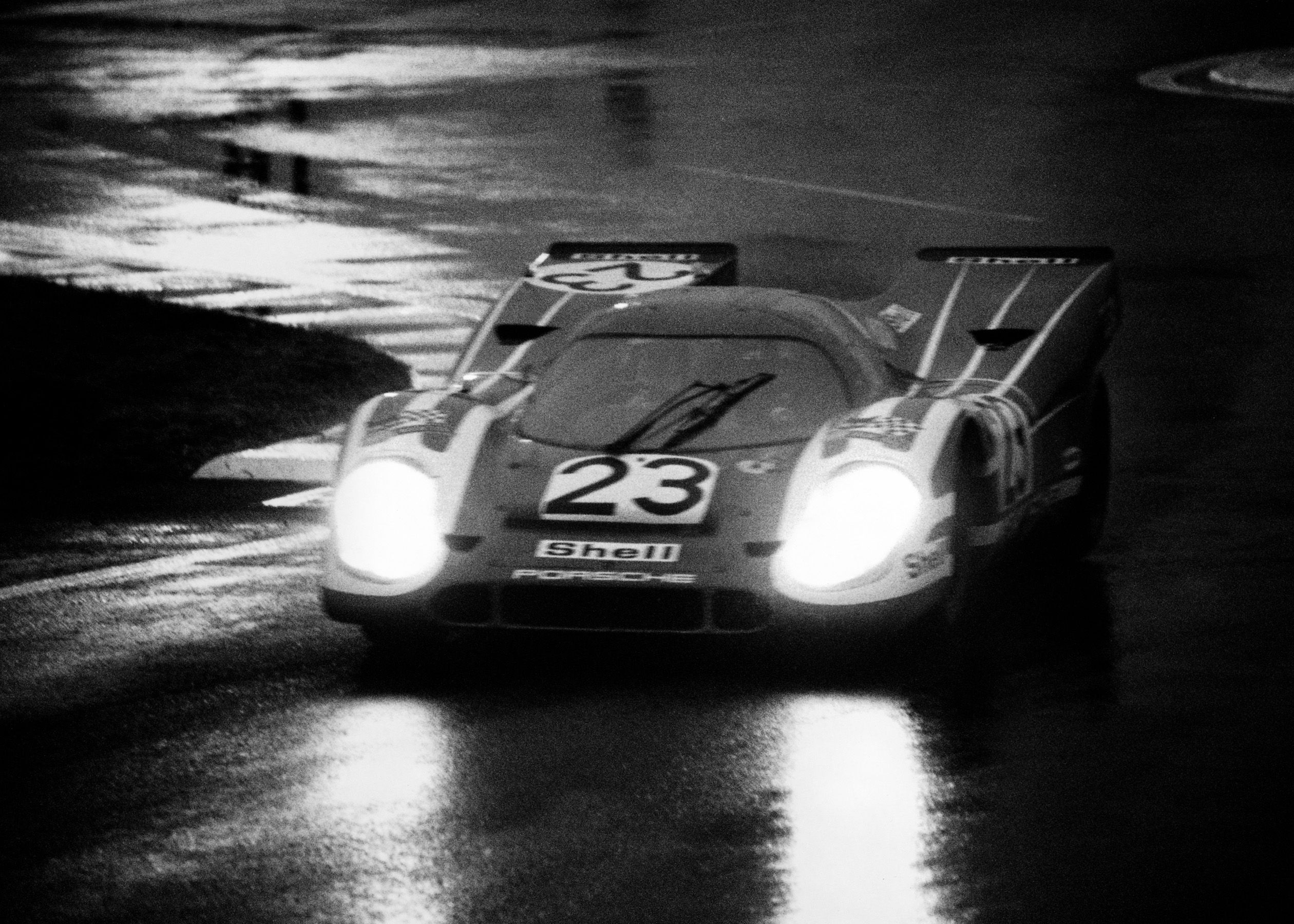

The early days were ominous, however, as Porsche's 917, the car that would eventually deliver the goods, was downright deadly with a gas-pressurized chassis that flexed so much mid-corner that the position of the shifter would literally change in real-time. Not only that, but the power delivery from the monstrous flat-12 engine designed by Hans Mezger was uneven with 200 horsepower available up until 5,000 rpm and then 350 horsepower more would be unleashed on the way up to 8,000 rpm. The body, too, generated lift instead of downforce and the narrow 13-inch rims made the car even more unstable.

Frank Gardner, who'd driven the 917 in its second-ever race, the 1969 Nurburgring 1,000-kilometer, said after the fact that he refused Porsche's offer to compete at Le Mans in one because he considered it'd ultimately interfere with his plans of being "the oldest man in racing". Others had no such problems related to self-preservation but the 917 did kill one of its handlers with John Woolfe dying after a fiery crash on the opening lap of the 1969 Le Mans race.

All of the misfortune and tragedy was in the back of Porsche's execs come 1970, especially since Ferdinand Piech's brainchild had drained Porsche's bank accounts (the parts alone to build the 25 chassis needed for homologation cost 5 million Deutsche Marks). But, with John Wyer at the helm and money pouring in from Grady Davis' Gulf Oil concern, there was an underlying air of confidence in the Porsche pits at Daytona. Leo Kinnunen and Pedro Rodriguez cruised to an easy victory around the Floridian banking and the writing was on the wall since Ferrari took months to iron out all the issues plaguing its otherwise fast 512S.

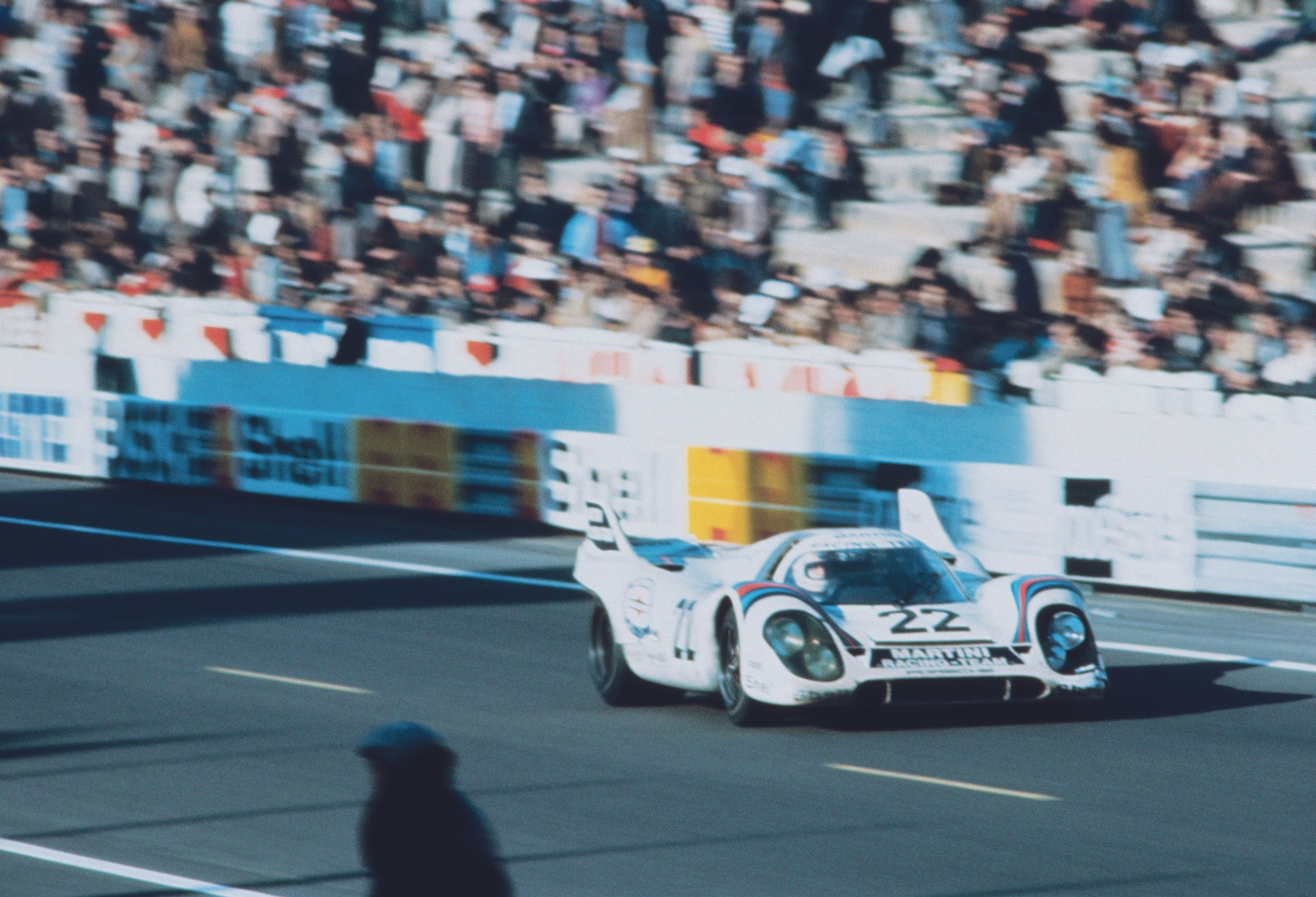

Wyer entered three cars while Porsche Salzburg, a semi-Works team managed by Piech himself, featured on the entry list with two 917s, a short-tail for Richard Attwood and Hans Herrmann and one of the two long-tails for Vic Elford and Kurt Ahrens Jr.

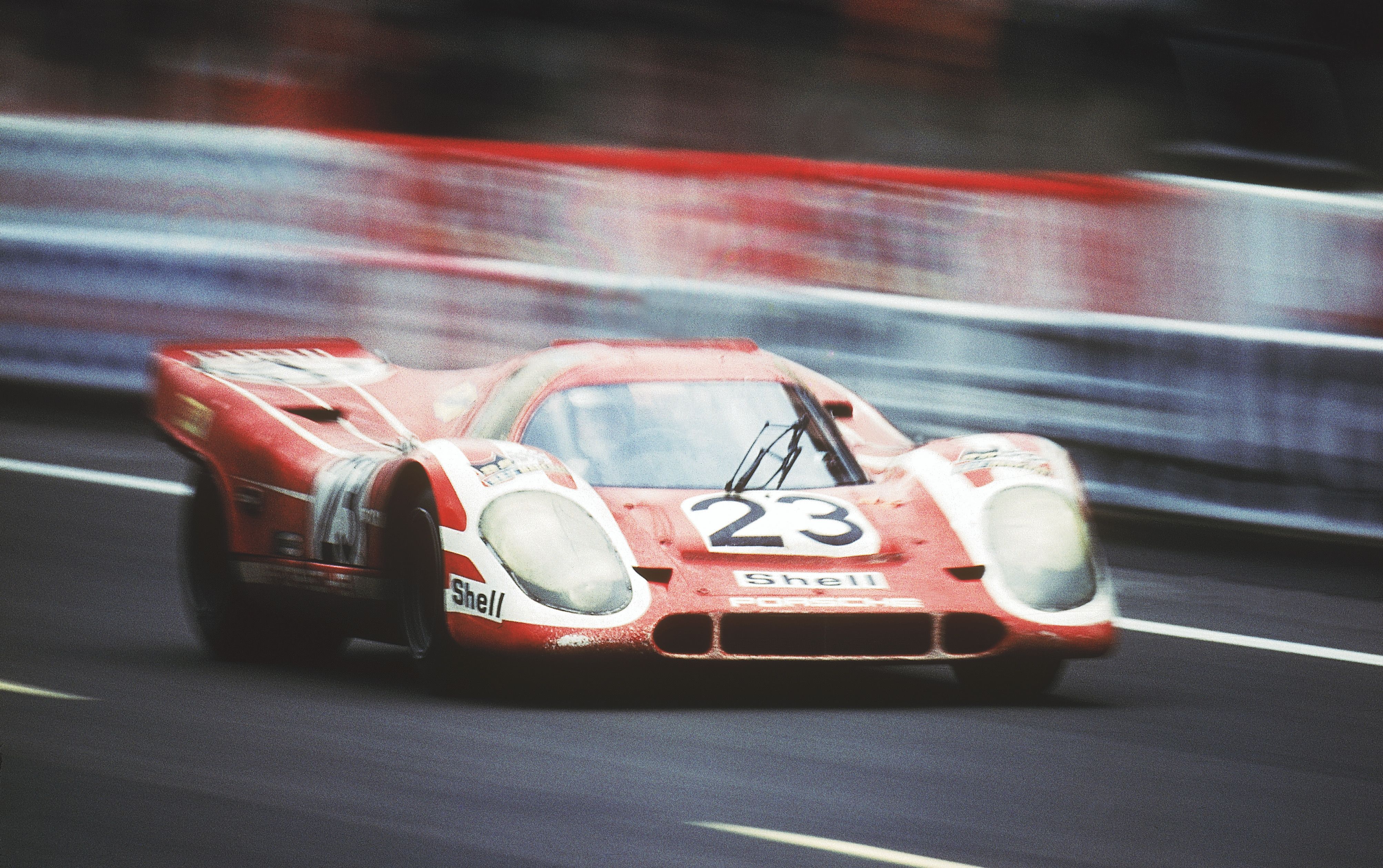

The No. 23 Attwood/Herrmann car wasn't among the favorites after qualifying having posted only the 16th fastest lap time almost 13 seconds in arrears of pole-sitter Elford. "From my point of view, before we started after qualifying, we were not going to win this race," said Attwood back in 2017. But, as it happened, a tremendous downpour played in their favor and by the time the race was over only seven cars of the 51 that had started the day before were classified.

"Hans started the race and I watched and it looked like a Grand Prix. We went on racing as it was a sprint race," remembered Attwood. " we tuned the speed according to the conditions we had to do 14 hours in terrible conditions. That was the challenge," he added. With damaged cars that'd crashed out littering the track left, right, and center Attwood and Herrmann tip-toed home to win by five laps over Messrs Larrousse and Kauhsen in the No. 3 Martini International 917 LH. As it happened, all of the 4.9-liter 917s failed and the two top finishers were both of the 4.5-liter variety. There was no Ferrari on the rostrum with all of the Works cars eliminated by crashes although a N.A.R.T. car was 'best of the rest' in fourth place behind the third-place Porsche 908/2 LH also entered by Martini.

1980 - Jean Rondeau does a Brabham

When you're born in Le Mans, you're almost destined to drive in the Big Race but Jean Rondeau did much more than just act as a grid filler. Disillusioned by a string of poor results in the '70s, Rondeau decided to develop his own car likely spurred on by the success that Ligier and more notably Matra was enjoying at the time. As it happened, he was the right man at the right time as both Matra and Ligier left the scene in the mid-'70s during the fuel crisis and Rondeau was there to capitalize.

Developing a car for a new category is never easy but Rondeau did just that probably thinking there wouldn't be many takers for the ACO's new-for-1976 GT Prototype category that allowed closed-top purpose-built race cars to race alongside the open-top Group 6 machines at Le Mans. However, unlike the Group 6 category that was split into two subdivisions based on engine capacity, the GTP class was a fuel formula from day one (just like Group C was) with GTP cars only allowed to consume a certain amount of gas over the entirety of the race.

As part of the deal, the two prototypes were named Inaltera and Rondeau was able to sign Henri Pescarolo, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, and Jean-Pierre Beltoise to drive for him. The No. 1 Pescarolo/Beltoise car qualified an impressive 12th overall humiliating the similar (in concept) WM-Peugeot P76.

In spite of the Cosworth DFV's infamous reputation for developing car-breaking vibrations over the course of a long race, both Inalteras finished their first race with Pescarolo coming home eighth overall. With the ACO and IMSA growing closer together (in 1976, a pair of IMSA GTO cars in John Greenwood's Corvette and Michael Keyser's Monza were allowed to race at Le Mans), Inaltera was able to contest the 1977 edition of the 24 Hours of Daytona, the first prototype to race there in four years.

At Le Mans, Rondeau and Jean Ragnotti finished fourth overall but Inaltera pulled the plug on the program unexpectedly at the season's end which meant Rondeau had to scramble to find sponsors if he was to keep going. With invaluable help coming of his PR manager, Marjorie Brosse, Rondeau got some money from SKF and was able to develop an updated Inaltera christened 'Rondeau M378' where the M was in honor of Marjorie. Then the M379 version arrived in 1979 and Rondeau began experiencing with a variety of engine options as the car was allowed to run in the Group 6 class.

For 1980, the entry list seemed to lack depth and, after losing in '79 to the Kremer-built 935 K3, Porsche decided to forgo entering a 936, instead deciding to run the 924 GTP. There was, however, one 936 on the grid but it was a Joest car disguised as a 908 on the entry list as Porsche didn't allow customers to race the 936 (Joest was more than just a 'customer', of course). Rondeau was represented by three cars, one of which started from the pole despite the fact that it was only the third-fastest in qualifying.

The race started just as a torrential downpour began to flood the track and this allowed the Dick Barbour-entered No. 70 Porsche 935 (the fastest qualifier) to lead before the engine began to splutter. After the skies cleared, it was time for Ickx and Joest to get in the lead with the Jaussaud/Rondeau No. 16 Rondeau running a steady second. Then, disaster struck in the Joest camp when the fuel injection belt snapped. A 14-minute repair job put the Porsche on the back foot and allowed Rondeau to take the lead.

But, by Sunday morning, the Porsche had reeled in the otherwise sluggish Rondeau and soon passed it. However, the gearbox of the Porsche failed and the "908" was back in the pits. Then, as Ickx was back going again and recuperating at times much as a minute a lap over a dehydrated Rondeau, the skies opened. With a disappearing cushion that once amounted to three laps after the Joest mechanics had to attend to the transmission, Jaussaud took over and crucially decided to stay on slicks defying the rain. Ickx, now back on the leading lap, called for wet-weather rubber but the time lost proved vital as Jaussaud managed to bring it home and win, even though he "ended up spinning out at Arnage without touching the barriers." As Jaussaud admits, "luck was with us that day." Rondeau would finish second and third at Le Mans in 1981 unable to beat the returning Works Porsche 936.

1990 - Jaguar's swansong

Jaguar, one of the toughest and most successful teams at Le Mans in the '50s, quit after failing to develop the infamous XJ-13 prototype for the 1966 racing season. 18 years later, American privateer Bob Tullius brought the Jaguar name back to Le Mans when he entered a pair of his XJR-5 prototypes that he developed in Group 44's shop to race in IMSA's GTP class.

The XJR-6 was designed by Tony Southgate and drew inspiration from the Ford C100. Its issues were the weight and the fact that it was prone to understeer heavily that was initially addressed by mounting a wing on the nose. Another issue was the engine which, at 550 pounds, was really heavy and caused the nose of the car to pitch mid-corner which required a really stiff anti-roll bar.

Luckily, the over-engineered carbon monocoque could take it but the weight of the N/A V-12s was always an issue and influenced how you drove the car because you always had to be mindful of how the engine could "pull" the car when exiting a bend, for instance.

The debut of the Tom Walkinshaw Racing Jaguar program was a successful one despite the flaws of the XJR-6: Martin Brundle qualified third at Mosport and briefly led before the car failed. Thereafter, he and Thackwell drove the sister car and went on to finish third overall, surprising even Norbert Singer of Porsche. For '86, the fuel system was redesigned and then the XJR-8 was introduced in 1987. By now, Jaguar had secured Silk Cut as the main sponsor and the Leaping Cats would run in white and purple up until 1991.

The XJR-8 was ultra-effective in the shorter rounds of the World Sports Car Championship and Jaguar ended up winning the title but Le Mans success was still one year away. Porsche came in with a trio of Rothmans cars and scored its seventh straight victory after Win Percy crashed out of the lead on Sunday morning. Then, in '88, Jaguar unveiled the XJR-9, effectively a revised XJR-8. Again the Jags dominated in the World Championship although the challenge from the Sauber-built Mercedes C9s mounted and one of them won at Jarama.

But there was no Sauber trouble at Circuit de la Sarthe as the AEG team didn't take the start amid fears of high-speed tire blowouts on the chicane-free Mulsanne Straight. It was, in the end, another Porsche v. Jaguar duel and this was one of the hardest fought ever with the Shell 962s and the Silk Cut Jags effectively running flat-out all the way, almost 20 years before this became common practice in endurance racing. In the end, Jaguar won ahead of the recovering No. 17 Porsche after Lammers drove the entirety of his last stint without shifting gears.

Two years later, Jaguar again had a real chance at winning Le Mans (there was no chance of victory in 1989 when the all-conquering C9 now in full factory colors swept the floor). Mercedes, now running the impressive C11 in the World Championship, elected to skip Le Mans and, with Porsche out completely as a factory team, Jaguar was seen as favorite due to the reliability of the V-12 engine and the car as a whole - the XJR-12 was a modified XJR-9 after all. But the Silk Cut machines weren't fast. Granted, Mark Blundell's Hail-Mary lap aboard his R90CK was insane and a whole six seconds quicker than the second-fastest car but the quickest Jag was down in seventh almost three seconds slower than that Brun Porsche.

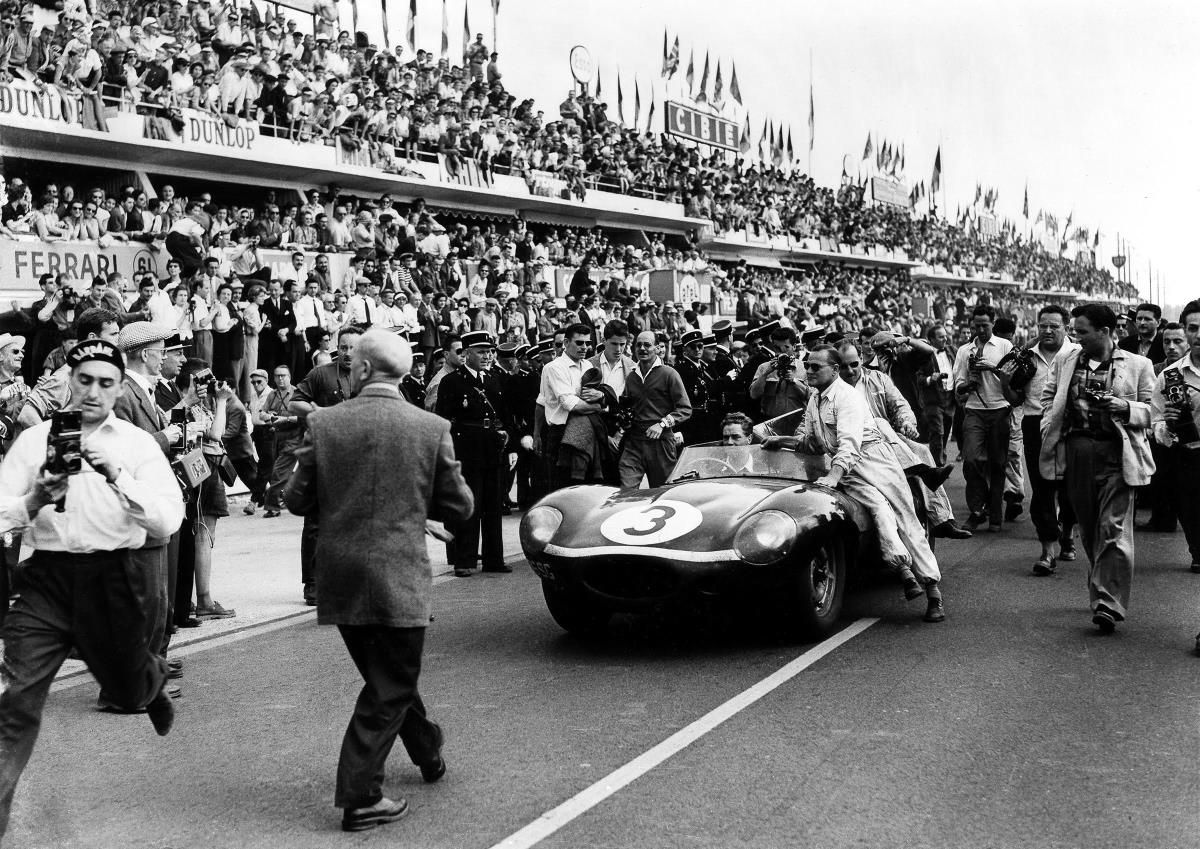

Then, four hours in, the pole-sitting Jaguar collected a Toyota but the No. 24 R90CK could continue. While Nissan had brought a ton of cars to the race (two for NPTI, two as part of the World Championship assault, as well as one R90CP from Japan), the No. 24 remained at the sharp-end of its assault. When daylight broke, the No. 3 Jaguar was in control after some inspired driving by American Price Cobb who handed over to Dane John Nielsen. Porsche, however, was hot on the Jag's heels, Brun taking over the job from the factory boys in '88.

The No. 1 Porsche and all of the R90CKs would also falter before the end while Oscar Laurrari was the hotshoe in the No. 16 Brun Porsche doing the chasing. Sadly, the engine of the Porsche let go in uncharacteristic fashion with merely 15 minutes to go allowing Jaguar to score a sweet 1-2 victory, Nielsen, Cobb, and Brundle winning by four laps.

2000 - The first day in the sun for the Audi steamroller

Audi wasn't a name that would echo in the ears of an endurance racing's fan in 1999 when a pair of R8Rs and a pair of R8Cs showed up at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Known for building all-wheel-drive rally cars (and some really good touring cars on top of that), Audi decided to go prototype racing against the best of the best in 1999 when the field featured Toyota, Mercedes-Benz, Nissan, and BMW. The two R8Cs built to GTP regulations were rushed to completion and it showed but the Joest-run R8R (R for Roadster) performed flawlessly and finished third and fourth overall, the result owning to their inherent lack of speed, not reliability.

The LMP-900 class was a minimum weight class meaning that all cars had to weigh no less than 900 kilos or 1,984 pounds to be eligible. Audi complied but also over-engineered the car down to its fabulous Turbo V-8 which is a staple of endurance racing.

You could argue the field was depleted as BMW skipped Le Mans and only did ALMS and all the other major manufacturers that were there in '99 were gone in '00 but, still, you gotta be there at the end of the 24 hours to spray the champagne. Add to the reliability the fact that the car was designed in such a way that you could swap the whole transaxle in four minutes flat. Joest's mechanics did it at Le Mans one year. Nobody believed it until they saw it live before their eyes.

Tom Kristensen won six times at Le Mans in the R8 and also just about everywhere else because the car was so versatile. "Some people would say Audi took a conservative approach with the R8, certainly compared with some of the more state-of-the-art and – shall we say – ‘bananas’ race cars that followed. The philosophy was, ‘if there is any problem, we need to be able to fix it,’ and that came all the way from board level down. The number-one priority was reliability. Without reliability, you cannot have 100% trust in your equipment, and you cannot perform. It was the perfect approach for Le Mans," said Kristensen.

In 2000, the third-place Audi was a whopping 21 laps ahead of the fourth-place Pescarolo and, in qualifying, the fastest of the R8s was three seconds quicker than the leading Mario Andretti-driven Panoz. You'd think, then, that the car was perfect, right? Well, Audi re-engineered it again for '01 - but, this time, under the skin only - and Kristensen is happy to point out the flaws of the 2000 version. "We had a bit of an issue with the brakes – we had to change discs and pads. The car was very fast, but in that first year the twin-turbocharged V8 engine had a lot of turbo lag, followed by a very aggressive response." The FSI system introduced in '01 cured the lag but Tom also remembers the R8s was, at first, quite understeer-y making it twitchy on new tires. It wouldn't be until 2009 that someone was able to beat Audi and by then the R8 had long since hit the retirement home...