Henri Pescarolo has been there and done it all. After a three-decade-long career as a driver, that yielded a plethora of sports car victories including four at Le Mans in the overall classification, he turned to team management and his Pescarolos were tantalizingly, better yet, painfully close to winning Le Mans in both 2005 and 2006 and ending Audi's stranglehold on the legendary French race. It is, then, easy to see why when Pescarolo speaks, people listen and the 78-year-old was particularly dismayed at the Lagardere Group's decision to put the car he drove to victory in the 1972 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, a Matra MS670, up for public auction.

France's pride and joy

Matra Sports was a racing team quite like no other. With backing from the French government and a wealth of experience on aerodynamics gathered throughout years of involvement in the aerospace industry, Matra went from zero to hero in under 10 years: Jackie Stewart bagged his first Formula 1 World Drivers' title driving for the Ken Tyrrell-managed Matra International team and then, between 1972 and 1974 Matra's open-top Group 6 prototypes were virtually unbeatable at Le Mans.

And then it was all over, Matra calling time on its racing involvement just as the oil crisis began to take its toll on the whole wide world. In an instant, it seemed, those raucous-sounding flashes of vivid blue were no more and, arguably, the blues took over the dismayed French fans for they'd have to wait four more years for another French win at Circuit de la Sarthe, four years in which the Renault-Alpine team grew to outgun Porsche's seemingly all-conquering factory team. But I digress - back to Matra, Henri Pescarolo, and the soon-to-be-sold MS670.

The story actually starts all the way back in 2003 when the Lagardere Group, owner of the Matra conglomerate at the time, shuttered the Romorantin plant after years of financial turmoil. With the closure came also the end of Matra as an entity since its road car arm, Matra Automobile, was declared bankrupt while the subsidiary active in the aerospace and military sectors, Matra Hautes Technologies (MHT/Matra High-Tech), had already been merged with the Aerospatiale concern four years prior.

A class action lawsuit was quickly brought forward by the employees who demanded hefty remuneration from the Lagardere Group on account of what they considered to be unfair and, more to the point, illegal treatment.

Eight years on, in January of 2020, a court ruling saw the Lagardere Group be forced to pay its former workers some €4.2 million ($4.9 million) in compensation money. As the Group is the current caretaker and owner of the Matra Museum in Romorantin-Lanthenay, close to the location of the plant, it was decided that a car from the collection would be sold off to fuel the compensation fund.

The latter, who would go on to be part of Matra's winning roster in '73 and '74 too, was infuriated by the news. Contacted by AFP, Pescarolo blasted the Lagardere Group's decision to part ways with what he describes a "monument of world and French motorsport." Describing the decision as "stupid," Pescarolo explained that he went to great lengths to get that car, as well as all of the others currently stored at the Matra Museum, recognized as part of French patrimony which would mean that they couldn't be sold off, nor could they leave permanently leave France.

However, Pescarolo said, the Lagardere Group wasn't helpful in the matter, which eventually came to naught, prompting the Frenchman to fear for the future of MS670 #01 which he thinks may end up in a private collection meaning it may no longer be displayed in a public place and, to add insult to injury, it may actually find permanent residence outside of France. "Arnaud Lagardere is destroying everything that his father created," concluded the former driver and team-owner for AFP.

As expected, a reaction from the Lagardere Group, which is nowadays run by Arnaud Lagardere, group founder Jean-Luc Lagardere's son, emerged rather quickly. Through the voice of Thierry Funck-Brentano, co-managing partner of the Group, the selling process was defended, as well as Lagardere's image. "I did not appreciate the disparaging comments made by some in the media targeting Arnaud Lagardère, who is not the owner of the MS 670 and who therefore had no personal interest in selling it," underlined Funck-Brentano.

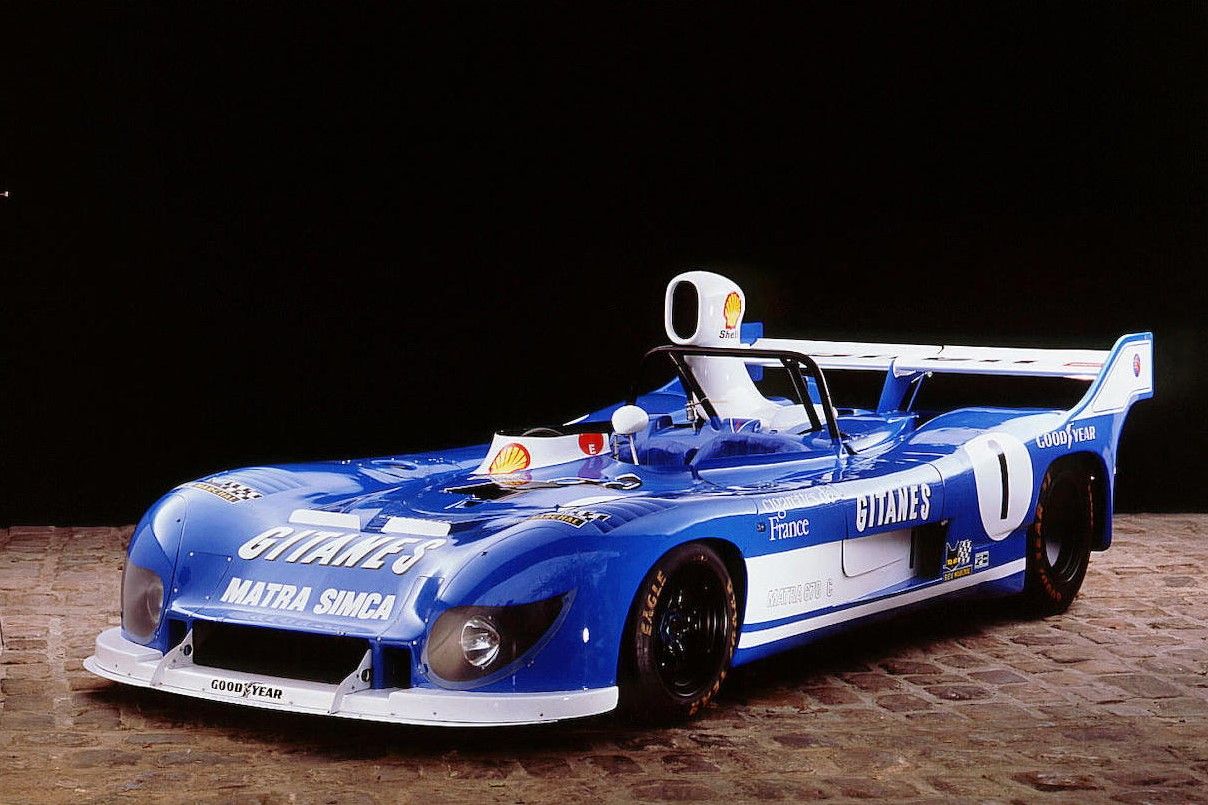

The car, now featuring Le Mans-style low-drag bodywork correspondent to its outing in the 1973 Le Mans Test Day (there is at least one other MS670 that has been seen publicly wearing the same livery as #01 did when winning Le Mans in 1972, as well as the correct aero setup) is set to go under the hammer next year. As the first French car to win Le Mans after a 22-year hiatus, it will probably headline Artcurial's February 5, 2021, sale that's taking place during the annual Retromobile show in Paris.

There is already an estimate out there on the car's value and if the appraisal is anywhere close to the money that the car will bring at auction, then the Lagardere Group shouldn't worry at all about paying back its former employees since Artcurial expects to get as much as $8.7 million for it which would surely make the MS670 one of the most expensive French cars ever to be sold at a public auction (the most expensive is a $10.4 million Bugatti Type 55 sold at Pebble Beach four years ago).

The story of the Briton and the Frenchman written in blue ink

On the one hand, Jean-Luc Lagardere's company built a series of quirky cars including the Rene Bonnet-designed D-Jet and the Bagheera and Murena sports cars of later years. Why were they weird? Well, take the Murena for instance. While you couldn't tell just by looking at its rather dull, subdued styling, this underpowered sports car hid a three-seat layout but, unlike in the case of the McLaren F1, the steering wheel was still on the left-hand side of the dash.

But the Murena was predated by something similarly peculiar, the tiny M530. Launched in 1967, just one short year after the Lamborghini Miura, it featured a mid-engine layout and pop-up headlights. The car, powered by a puny 1.7-liter, V-4 Taunus engine, mustn't be confused with a product of Matra's other production line, namely the R530 medium-range air-to-air missile.

Sadly, though, not many remember the street-bound Matra models and that's because Lagardere bankrolled a race program that was supposed to take over the world and it did just that in less than a decade. The plan was simple, at least on paper: first off, Matra would build single-seaters for the lower formulae, namely Formula 3 and Formula 2, which would be used to dominate the French championships.

Thereafter, with a few titles in the bag, Matra would focus its attention on Formula 1 and sports car racing simultaneously with the aim of winning the World Title in both disciplines. If it sounds far-fetched that's because it is. After all, consider just how much money (the actual amount is unknown even to this day) Ford had to pour into its Le Mans program to win the fabled race. But Matra wanted to do more than just win Le Mans. Matra wanted the whole cake. Matra cars powered by Matra engines were supposed to be winning everywhere apart from World Rally stages. What's more amazing is that Matra pulled it off - with a helping hand from the French government but they did it nonetheless.

So, by 1969 Jackie Stewart was F1's newest World Driver's Champion driving a Matra, albeit powered by the all-conquering Ford-Cosworth DFV V-8. That was good enough for Lagardere who probably realized that the team's lanky V-12s were probably never going to match the DFVs in F1. However, they'd find a better home somewhere else.

While Matra was in its fourth year of tackling F1 in 1969, it was also in its fourth year of racing sports cars at Le Mans. It had all started back in 1966 when the first patriotic blue mid-engined Matra MS620s showed up at Le Mans. Unusually, they were powered by BRM engines, mainly because Matra's own V-12 wasn't ready yet, and they underperformed. The MS620 was quickly ushered away and replaced by the much more purposeful-looking MS630 by 1968. That too hid under its lightweight clamshell a BRM engine which simply couldn't last.

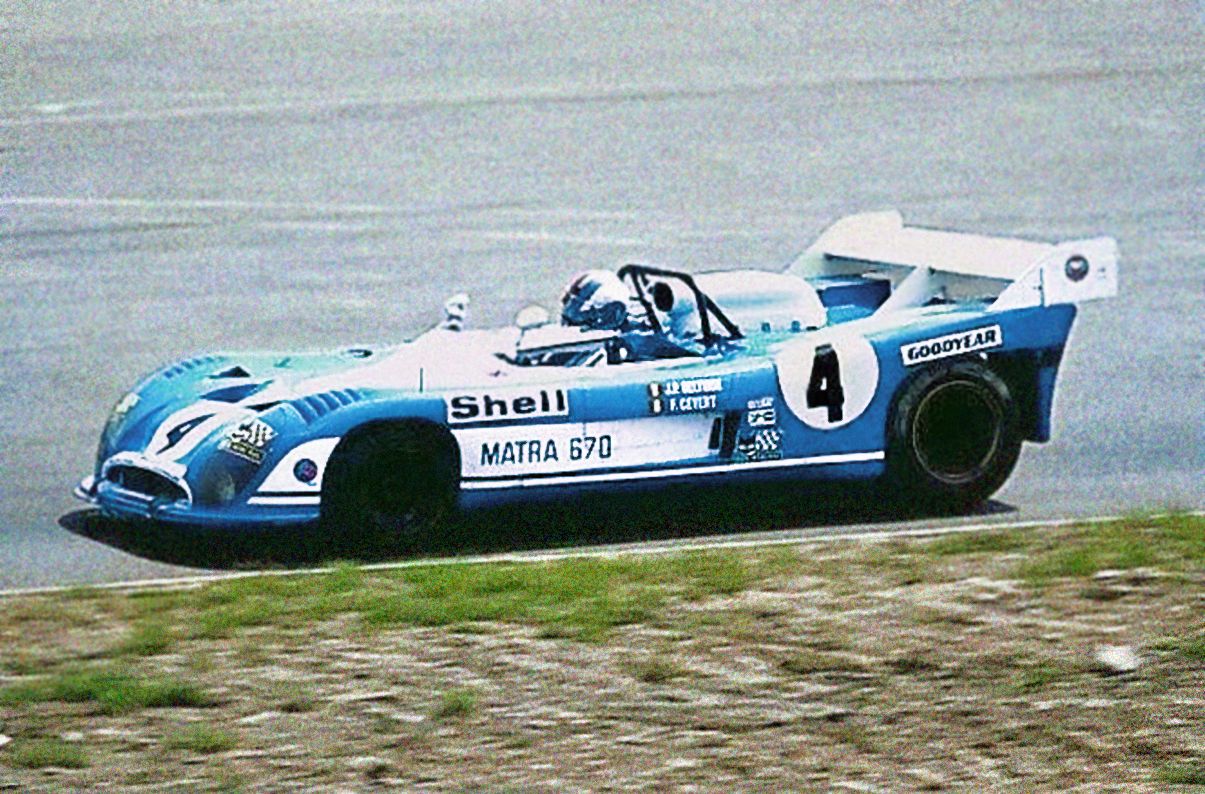

Matra employed basically an entire generation of French drivers including the likes of Cevert, Jabouille, Beltoise, Servoz-Gavin, or Pescarolo. The lineups were at times bolstered by international talent but it was to no avail as the cars were frail. Then, for the delayed 1968 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Georges Martin's 60-degree, three-liter V-12 was finally ready. It took a while for the engine to be toughened up for endurance, especially since Matra was still focusing on F1 at the time, but the pieces of the puzzle seemed to finally align at Le Mans in 1969.

In spite of a dreadful crash in practice for Pescarolo aboard the new, long-tailed MS640, Matra continued unabated and brought four cars at Le Mans including three open-top examples. In the pre-race Test Day, one such car, nee MS650, had been second fastest and then, in the race, Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Piers Courage (Briton with a French name) finished fourth, directly ahead of the closed-cockpit MS630 of Jean Guichet and Ferrari ex-pat Nino Vaccarella of Italy. Another Matra was seventh and, if that wasn't reason enough to party for Lagardere's men, the MS650 won the Paris 1,000-kilometer race at Linas Monthlery ahead of Porsche, Lola, Ford, and everyone in between.

But then the 5.0-liter sports cars took over and Matra's three-liter roadsters simply couldn't keep up. 1971 brought about a revision to the MS650 that was rebadged as the MS660 and, indeed, the car was well on its way to a great result at Le Mans in the hands of Chris Amon and Jean-Pierre Beltoise but the team couldn't keep up with its excessive oil consumption and, eventually, the fuel injection system failed. By then, however, the writing was on the wall for the Porsche 917 and the Ferrari 512S which was good news for Matra.

"I was very upset with because they had pushed me out of the F1 team in 1970, even though I’d had fantastic results. It was my first full year in Formula 1, and the car was not so competitive, yet I was third at Monaco," remembered Pescarolo speaking to Motor Sport Magazine back in 2007. Pescarolo, who, remember, had almost given his life for Matra merely one year before being sacked, vowed to never drive for the French manufacturer. But the bearded Pescarolo and his iconic green helmet would be seen again in the cockpit of a Matra by 1972. "I saw it was the right team and the right car, and that there was a chance to win," lamented Henri who, at the time, had no wins under his belt at Le Mans.

Matra decided to develop a whole new car for 1972, the MS670, and, to further increase its chances of victory in the big race, Lagardere's men ignored the entire world championship and only raced the car at Le Mans. Meanwhile, Ferrari with its proven 312 PB (that had debuted in 1971) steamrolled to a perfect record of 10 victories out of 10 starts.

But the 312 PBs never raced at Le Mans. Despite clocking in the second-fastest time during the Test Day that year, quicker even than the sole Matra on-site, an MS660 C, Enzo Ferrari decided to skip the event fearing that the F1-derived engines powering his prototypes would simply break. He could push the organizers of the 24 Hours of Daytona to shorten the length of the American season-opener for the very same reason but no amount of sweet talk and behind-the-scenes string-pulling would make the ACO cut the length of the Le Mans race and Enzo knew it.

So, Matra's opposition came from Alfa Romeo, Mirage, Porsche, and Lola. Well, sort of. While the Alfa Romeo team was the pukka Works team running under the Autodelta banner, Porsche and Lola's efforts were more on the privateer side and John Wyer's Mirages dropped out before the race too. Porsche, for instance, was relying upon a handful of aging 908s in various trims as well as, awkwardly, a 1968-spec 908 LH entered by the Austrian Siffert ATE team (read 'Joest Racing) that was effectively taken straight out of Porsche's museum to be raced by Reinhold Joest and his paying co-drivers. The Lolas were two T280s entered by Jo Bonnier's team that received some support from Lola Cars back in the UK but not enough to make them proper contenders - in spite of what Bonnier's win in the four-hour Le Mans 'prep race' in March may have suggested.

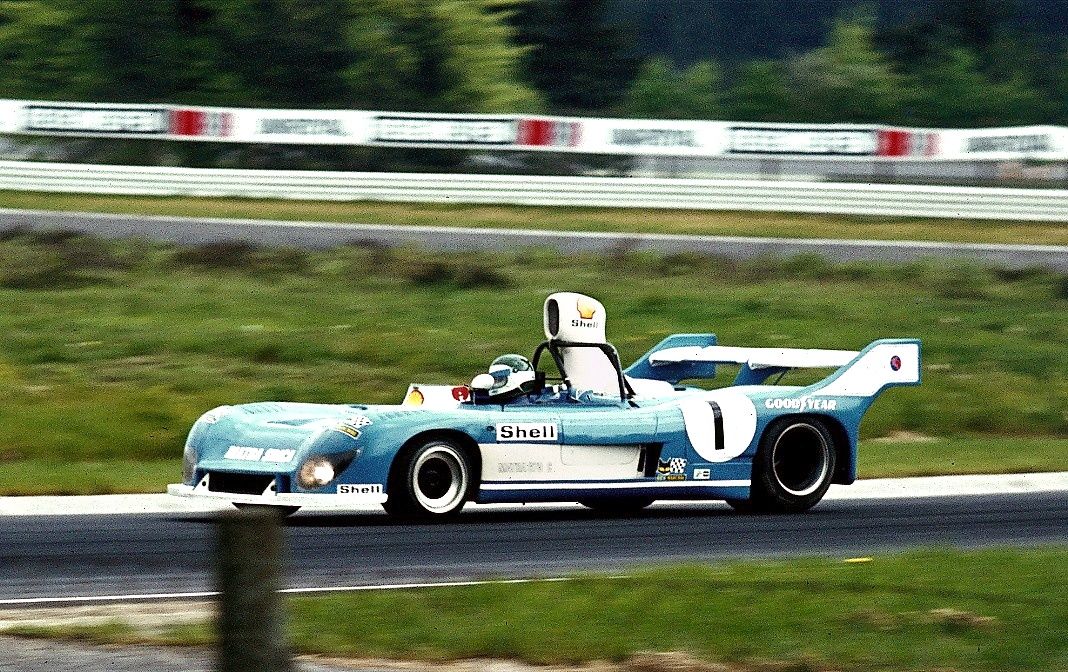

In short, Matra had to win, as Motor Sport's Denis Jenkinson wrote at the time, or else they'd be the 'laughing stock of racing'. To avoid embarrassment and thus deliver the first French outright win at Le Mans since Rosier's unlikely success in 1950, the team ran multiple 24-hour-long tests around the then-new Paul Ricard track near Le Castellet. Then the team brought four cars to the race: three MS670s and one MS660 C. They qualified first, second, third, and eighth and never looked back in the race.

Henri Pescarolo drove the No. 15 car, chassis #01, but he wasn't too happy about it before the race. "When they told me I would be driving with Graham Hil, at first, I said, ‘No, I don’t want him.’ I was concerned about how he would cope with the conditions, the dangers," Pescarolo said. "Le Mans is so different from F1. It’s a road race, the most dangerous race at that time. I said, ‘What if it’s raining in the night, or there’s fog in the morning, do you think he will be prepared to take risks?’"

Hill, who was 13 years older than Pescarolo, was no stranger to sports car racing having driven a plethora of GTs and prototypes throughout the '60s and even came close to winning when he drove a Maranello Concessionaires-entered Ferrari in 1964, but he hadn't driven at Le Mans in four years' time by then. However, the decision was already taken and Henri had to be a team player. " became my team-mate – and in a very short time a real friend too," Pescarolo added. "It was strange. It was as if it had always been like that." Moreover, Pescarolo remembered, Hill proved he still got it by being fast come rain or shine which proved helpful given that the race was held in mixed conditions with rain a constant factor.

"When I looked at his lap times during the night, and in the rain, I thought, ‘Okay, I can sleep now.’ His speed in the night was one of the reasons we won," Pescarolo underlined. "We beat the other Matras with their F1 drivers – Francois Cevert, Jean-Pierre Beltoise – because we drove as a team. It was the same with Gerard Larrousse and me in the two years after. But with Graham, it was something very, very special. I was so pleased for him because that was his big target: to win Le Mans."

Since 1972, no other driver has been able to count the Triple Crown among his achievements and it can be argued that Hill's unique achievement had a lot to do with both Pescarolo and the MS670, something that Graham himself acknowledged at the time. "My car was still pulling the same revs down the Mulsanne Straight at the end of the race as it had at the start. A fantastic car – and the best team I’ve ever driven for at Le Mans."