Peugeot, the proud manufacturer that stopped at nothing to win the grueling 24 Hours of Le Mans in the early '90s and again in the late '00s and early '10s, will be back at Le Mans in the summer of 2023 as part of a fully-fledged assault on the FIA World Endurance Championship from 2022 onwards. Peugeot, like Toyota, will compete with a bespoke hybrid hypercar not based on a current production model and the work will be carried out in-house by Peugeot Sport, although it's believed outside partners such as ORECA could offer some assistance. Peugeot will thus make its debut in the FIA WEC in the third season of the new 'Hypercar' regulations that come into effect next year for the 2020-2021 season.

Peugeot Sport, first with Frenchman Jean Todt at the helm and then with his pal Olivier Quesnel, has won the 24 Hours of Le Mans three times since it first took part in the French race all the way back in 1926. The company has also enjoyed success as an engine supplier, powering the early Pescarolos as well as the WM P88 Group C car, the fastest car to ever race at Le Mans that reached a top speed of 253 mph in 1988. With almost a century of history at Circuit de la Sarthe by the time Peugeot Sport's new hypercar will debut in 2022, it's safe to say the French automaker set its own bar very high for its comeback. In the light of this challenge - one that the French engineers most definitely relish - let's take a quick look back at Peugeot's history at Le Mans and in endurance racing as a whole.

The Lion is back and it'll finally roar with hybrid strength

The number 13 is, in many cultures, synonymous with bad luck. You won't find the 13th floor in many tall U.S. buildings, for instance, with the labeling often skipping from 12 to 14.

Peugeot announced its return as if it was nothing - via a simple tweet published by the official Peugeot account. It confirmed rumors dating back to October when specialized outlet Sportscar365.com quoted French publication Le Maine Libre saying that Peugeot could be back as part of a privateer effort under the Swiss banner of Rebellion Racing.

That team, a long-standing contender in the FIA WEC, is currently racing an ORECA-developed LMP1 prototype, the Rebellion R13 powered by a Gibson GL458 4.5-liter V-8. The team competed in the past with both Judd and Toyota engines. A deal with Peugeot, who'd act as the engine supplier for the team, was said to be on the horizon. It was also said that the debut of this partnership, also consisting of ORECA as the chassis builder, could come as early as 2021. In an unexpected twist, reality surpassed speculation and Peugeot will instead be back in full Works capacity, albeit a year later than originally suggested.

Peugeot previously looked at ways of getting back into the fray in 2017 but ultimately decided to direct its motorsport budget elsewhere at a time when Porsche was announcing its exit, closely following the end of Audi Sport Team Joest's involvement in the FIA WEC. Now, though, the pieces came together due, in part, to the FIA and ACO's push to deliver a cheaper top-tier class in place of the outgoing LMP1 category.

"Cost savings permitted by the WEC’s new 'Hypercar' regulations and the confirmation that the series will feature hybrid power units led the Groupe PSA Executive Committee to approve the Peugeot brand’s proposal to participate in the world’s premier endurance racing championship from 2022," said the company in a statement shortly after announcing its new global motorsport program. "The changes that the FIA WEC is introducing fit now with the transition we are undergoing ourselves with the electrification of our range and the launch of high-performance products, developed in close association with PSA Motorsport," said Peugeot Brand Director Jean-Philippe Imparato.

PSA Motorsport boss Jean-Marc Finot hailed the decision to re-enter sports car racing as "courageous" during DS Techeetah's FIA Formula E Championship launch event in Paris last week. "Everyone knows that the car industry is currently tricky but it means as a group we trust in our future," Finot added while also pointing out that "we will use the same skills for Hypercar project as has been the experience we have being getting in Formula E." While we will find out more about the project next year, we do know it'll be developed at PSA Motorsport's headquarters in Satory, once the home of the Citroen Racing WRC team.

Other privateers are set to take part too, with American Jim Glickenhaus announcing his 'Hypercar' program with Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus while Colin Kolles' ByKolles team is also developing a new car. Other manufacturers are understood to have taken a 'wait-and-see' approach, with McLaren and Koenigsegg often mentioned as possible entrants in the future.

It's undoubtedly clear that whatever path Peugeot chooses in developing its car, it has to be a contender right out of the box but things weren't always the same although each and every entry of the 'Lion' at Le Mans was met with cheers from the fans, always eager to urge on yet another French automaker and Peugeot's always been one of the big players in the hexagon. Oh, and the whole thing might just spawn a road-going hypercar too. The rules are a bit vague on whether or not each manufacturer has to build and sell 20 road-going examples of the vehicle they intend to race and it seems Toyota may only build one example.

Humble beginnings in the early days of the 24 Hours of Le Mans

Peugeot was no stranger to racing success by the time it decided to contest the fourth edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1926. It had previously conquered America by winning the coveted Indy 500 twice, first in 1913 with Jules Goux and again in 1916 with Dario Resta. Georges Boillot also came close to winning the 500-mile oval race in 1914 when he was the first to surpass the 100 mph mark in practice.

Peugeot also knew how to manage long-distance races, Goux and Boillot also driving in the early days in the French Grand Prix, the world's biggest motor race to be held on a circuit back then. Boillot was almighty and won two times on the trot, first in 1912 against the supremely talented David Bruce-Brown who drove for Fiat despite being an American, and again in 1913. But, by the '20s, Peugeot's star in top-level motorsports had arguably faded and the French company sensed Le Mans could be the stage of its comeback.

A pair of Peugeot Type 174S was entered that year, one for the duo of Andre Boillot and Louis Rigal and the other entrusted to Louis Wagner and Christian Dauvergne. Boillot, Georges' younger brother, was a skilled wheelman in his own right winning the 1919 edition of the Targa Florio as well as punching above his weight routinely in the early '20s in the French and Monegasque Grand Prix. But he could not turn the lackluster Type 174S with its 100 horsepower 4.0-liter, four-pot engine into a winner.

The pair of open-top sedans is able to stay with the Lorraine, Overland, and Bentley entries all throughout the night, battling for position until the early hours of Sunday when one car gets disqualified after being push-started to rejoin following a scheduled pit stop and the other is also shown the black flag after its windshield mounts break. After this disappointing outing, Peugeot decided against coming back in 1927 and, in fact, the world would not see a Works-backed Peugeot at Le Mans until 1991.

Privateer efforts and engine supply deals punctuate the early post-War era

In the decades separating the two World Wars, Peugeot briefly returned to Le Mans as a result of the ambition of Emile Darl'Mat. Darl'Mat was a Peugeot dealer in the Paris area and became known for his one-off creations based on the 201, 301, and 601 coupes and convertibles. Basically, people would show up at his shop with a standard Peugeot and then the Darl'Mat craftsmen would turn them into elegant Art Deco sculptures on wheels.

Collaborating with coachbuilder Marcel Pourtout, Darl'Mat captured the attention of Peugeot and its designer Georges Paulin who worked together to build a series of open-top sports cars that would wear the Darl'Mat badge. First based on the 302 and later the 402 chassis, these sleek two-door models were aerodynamically tested and featured some striking details such as the circular vents on the sides of each hood.

On the advice of driver Andre de Cortanze (who later became a race director at the 24 Hours of Le Mans), Darl'Mat set about building some special roadster to take to Le Mans. All sported an aluminum body, significantly lighter than the steel-bodied road cars that made use of stock Peugeot drivetrains, low-set driving lights below the headlights, and jack mounts for easy access during pit stops. They also lacked doors, the engines were updated with dual Memini carbs, and the stock gearbox was replaced with one from Cotal.

In 1937, all of the three Darl'Mat roadsters reached the finish line with Marcel Contet/Jean Pujol arriving home in seventh place overall, one spot ahead of team-mates Charles de Cortanze and Maurice Serre. The third Peugeot, also equipped with the 2.0-liter engine, finished tenth. In 1938, however, only one of the three 402 DS Darl'Mats entered finished the 24-hour race. Charles de Cortanze and Marcel Contet partnered for a fifth-place finish that year, Peugeot's best result until the '90s.

Peugeot would be back at Circuit de la Sarthe after the War with consecutive entries between 1952 and 1955 courtesy of Alexandre Constantin. The local tuner fitted the diminutive 1.3-liter inline-four engine of the Peugeot 203 with a compressor to boost its underwhelming output of just 45 horsepower and 59 pound-feet of torque.

Constantin's 203 was modified for the race, morphing from a four-door sedan into a two-door coupe. The car, painted in France's national racing color of light blue, retired 15 hours in after an off-track excursion. Undeterred, Constantin came back in 1953 with an even sleeker bodywork for his 203 including reshaped lower fenders and a sloping roofline. By finishing 25th overall, Constantin's Peugeot (that he shared with Michel Arnaud) became the first car featuring a compressor that finished the 24 Hours of Le Mans since the winning Bugatti T75C Tank of 1939.

For the 1954 edition of the race, one that would see flooding thunderstorms affect the running, Constantin was back with a hand-beaten sports car. The low-slung machine, christened as the 'Constantin Peugeot 203 Speciale Barquette', was underpinned by the same Peugeot 203 chassis and failed to finish due to gearbox maladies. The Frenchman appeared for the second and last time with his aluminum oddity in 1955 and, in what seemed like a deja-vu, he was forced to retired when transmission gave up during the ninth hour of the race.

It would be another 11 years before a Peugeot-engined car would re-emerge on the grid at Le Mans. Known as the CD SP66, the slippery prototype comes with an interesting - if convoluted - backstory. The initials that make up the name of this bizarre creation are those of Charles Deutsch, the man behind the whole thing.

Deutsch was the co-founder, in the days before the Second World War, of DB. The 'B' in the name is the initial of Rene Bonnet who bought Deutsch family's existing coach-building shop in 1932 and set about building sports cars with Deutsch. The first project was a race car based on the Citroen Traction Avant 11CV. After 1945, the two started developing bespoke spyders sat on Panhard chassis and with Panhard engines and gearboxes after making use of Citroen internals for their first creations like the DB2 and the DB4 (no relation with any Aston Martin model, of course).

Despite the small capacity of Panhard's flat-twin engine, the aerodynamic coach-works designed by Deutsch helped the DB-Panhard cars to be effective at Le Mans and on other fast tracks. For instance, a DB-Panhard won its class in the 1952 running of the 12 Hours of Sebring. The success DB achieved in the competition bolstered Panhard's reputation and, as a result, the two companies developed a close-knit partnership to the point that DB products would be showcased on Panhard's stand at the Paris Auto Show in the '50s.

It all came crumbling down in 1961 when Deutsch and Bonnet split following numerous disagreements over what the next step of the company should be. One of them was adamant that the rear-mid-engine layout was the future while the other was a firm believer in the FF layout. Deutsch quickly formed CD after the split and continued alongside Panhard the development of aerodynamic prototypes, establishing SERA-CD (Société d'Etudes et Réalisation Automobiles - Charles Deutsch, the Society for the Study and Creation of Automobiles) that same year.

With a low profile and clean surfaces, the CD LM64 was the first to feature a pair of high-rising fins on the rear deck, fins that, in theory, worked with the carefully shaped underbody to create some semblance of ground effects. It is unclear how much downforce (if any) the LM64 produced but it was a very efficient racer winning the Index of Thermal Performance award in 1964 that was awarded every year to the car with the best fuel economy during the race. After the CD LM64 (which was powered by a Panhard unit, Deutsch also experimenting with DKW power in 1963) came 12 months of hiatus that proved to be well spent by the designers and engineers at SERA-CD.

For 1966, they unveiled the CD SP66, a brand-new car with a chassis designed by Lucien Romano and Robert Choulet and styling by Daniel Pasquini. With a paltry 1.1-liter 103 horsepower Peugeot 204 engine (after heavy mods since the stock unit only put out 53 ponies), the SP66 boasted with a drag coefficient of just 0.13 enabling it to reach 153 mph on the Mulsanne straight. The tail fins were still present when racing at Le Mans but, at other venues, a finless tail section would be mounted. The five-speed box was also of Peugeot origin and it sent the power to the rear wheels that only had to move 1,631 pounds.

Three cars were entered in the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans, a race now (even more) famous after the release of the Ford v Ferrari movie starring Christian Bale as Ken Miles and Matt Damon as Carroll Shelby. But the CDs had no business doing battle with the 7.0-liter Ford Mk. II racers although they did compete on the same strip of tarmac for as long as the French cars lasted - none until the flag, that is. The story repeated itself in 1967 when both of the CD SP66Cs retired. But it wasn't all frustration for Deutsch and his crew who were relatively successful in other French races such as the Reims 12 Hours and the 1966 Coupes du Salon at Linas Monthlery that ended with a CD victory in the SP 1.15-liter category. Thereafter, Deutsch threw the towel and became the director of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1969, a position he'd hold until 1980, the year of his death.

The fashion of two-letter manufacturer names didn't die with CD as, in 1967, the same year of CD's last Le Mans start, two other gentlemen got together to form another entity that would compete at Le Mans with Peugeot power. Their names were Gerard Welter and Michel Meunier, Peugeot designers by day and Societe WM bosses by night (and on the weekends).

The arrival of WM on the scene and the pursuit of pure speed

Just like Deutsch before them, Meunier and Welter started off in 1968 by racing a modified Peugeot 204 at Magny Cours and in other French national races. The first model to feature a unique, coupe bodywork was the WM P69 that was penned by Welter and featured a 100-horsepower engine tuned by Meunier. It's the result of no less than 900 man-hours and the duo took it to the Paris 1,000-kilometer race at Linas-Monthlery where, on the banking, the car topped out at 130 mph, 50 mph more than a Peugeot 204.

The following year, Meunier and Welter unveiled the much more radical WM P70. Looking a lot more like a proper prototype, the P70's steel unibody chassis is clothed with a composite body. The engine is a 1.3-liter that develops 120 horsepower thanks to a Meunier-designed camshaft and double Webers. Weighing in at just 1,212 pounds, the purposeful P70 could reach almost 140 mph flat out but it was its agility that was tested in the 1970 edition of the Tour de France, its first competitive outing.

After that, Welter and Meunier took the car to Le Mans, appearing at the test in April 1971 when it reeled in a 4:49.400, enough to allow it to compete in the three-hour race that same month. Clutch problems intervene, however, and the car never takes the start. All the experience gathered throughout 1971 sends Meunier and Welter back to the drawing board while the car is still campaigned up until 1972 by Philippe de Souza.

Busy with their day jobs and lacking the necessary funds, Welter and Meunier needed five years to return with a new car. Welter, for instance, was one of Peugeot's most prominent designers. Over the years, he proved instrumental in the development of some legendary models such as the 205. He also presided over the design of the Peugeot 405, the 406 Coupe, and, in the 21st century, the 407, the 908RC Concept and, lastly, the RCZ Coupe.

The WM P76 arrived one year before the Inaltera GTP and thus was perceived as an oddity. The reason is that it featured a closed-cockpit body at a time when sports prototypes in the World Endurance Championship were open-top two-seaters as per Group 6 rules. The P76 was entered in the new GTP class, one aimed at "two-seater coupes weighing less than 1,874 pounds and less than 43.3 inches, with a maximum consumption of 9 mpg," according to Automobilsport. The engine powering the P76, as well as other subsequent WMs wasn't 100% a Peugeot creation.

In the early '70s, Peugeot signed an engineering agreement with Renault and Volvo that led to the introduction of a number of jointly designed powerplants meant to be incorporated in the lineups of all of the three partners in the project. The Peugeot PRV 2.7-liter ZNS4 V-6 was frantically improved by WM over the course of a number of seasons with turbos also being added for the 1979 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Likewise, the basic design of the P76 was also refined and it spawned the P77, P78, P79, and the P79/80.

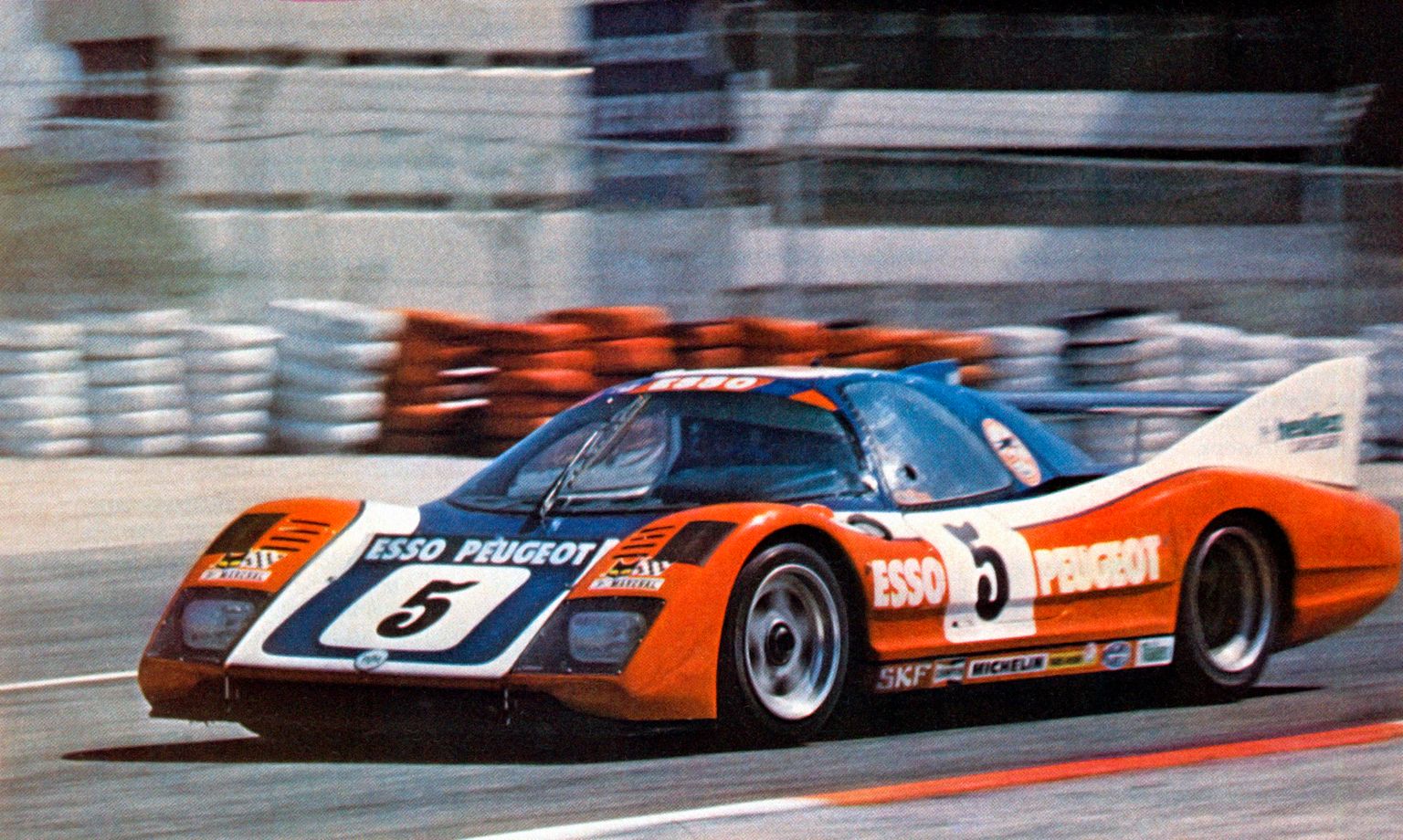

Always with a relatively narrow track and very aerodynamic body, WM kept coming back at Le Mans with a faster car year in and year out and by fast we mean faster down the Mulsanne straight. That's not to say Meunier and Welter ignored the aspect of reliability, something that can be attested by the performance of the No. 5 Esso-sponsored WM P79/80 which, in the hands of Guy Frequelin and long-time WM driver Roger Dorchy, finished fourth overall at Le Mans in 1980 after starting ninth overall. A class win had already been achieved in 1979 with a 14th place outright for Raulet/Mamers.

In 1981, a new-look bodywork debuted. The wing was now bigger and the rear deck now came down in line with the side skirts to cover the rear wheels completely. It was at that point that WM decided to focus on outright speed instead of resilience, although it never stopped employing quality drivers. The likes of Didier Pironi, Thierry Boutsen, Claude Ballot-Lena, and Marc Sourd all raced for WM and even Alain Prost was supposed to tackle Le Mans with a Meunier-Welter car in 1979.

The dedication to go faster than anyone else was first highlighted by Roger Dorchy's fighting opening laps in the 1984 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans when he took the lead from the all-conquering Porsche 956 but was denied of a longer spell at the top of the field when a faulty brake bias sent the car in the guardrails during the second lap. Still, the signs were already there.

While the older P83B reached the finish line on two occasions, in 1985 with Jean Rondeau among the driving talents, and again in 1986 (a 12th place overall for the same P83B that was now entered as a C2 car), WM was determined to develop a car able to reach and surpass 248 mph down the 3.7-mile long National Road 138 or, as we all race fans know it, the Mulsanne Straight. The P87 was the first car designed to reach this milestone. It featured side-mounted water coolers, together with the turbocharger intercoolers, all getting air via an ingenious system that required no snorkels that would've otherwise ruined the airflow over the bodywork and slow the P87 down.

"The P87 was clothed in body panels developed in a series of Peugeot-financed tests in the fixed floor St Cyr wind tunnel in Paris that took place each Sunday over a four-month period during the winter of 1986-87," according to Dailysportscar.com. Indeed, the decision to go for an apparently unfathomable speed record attracted the attention of Peugeot bosses that allowed WM to use its wind tunnel but funding from the factory was still negligible. With a narrow wheel track and a widened body (compared to the P86), the P87's wheels were almost fully concealed and, underneath, there were huge venturi tunnels to create downforce via ground effect.

"The drag co-efficient for the P400 cars was between 0.25 – 0.26 and the lift to drag ratio was 2.0. So it had exactly what we wanted – very low drag and not very high downforce. I don’t recall the precise figures but with larger tunnels and a shorter flat floor than the LMP cars have today the P400 cars had much better aerodynamic stability especially over bumps," said WM Engineer Vincent Soulignac.

Still fighting to survive on a shoestring budget - with unpaid Peugeot employees acting as team personnel in their free time - WM struggled to sort the electronic fuel management system and this plagued its 1987 record attempt. However, when it did run, Dorchy reached 221 mph on the Mulsanne Straight.

Before the 1987 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the P87 successfully attempted to break the public road speed record. A brand-new and unopened portion of the St Quentin – Rheims highway was used and cameras from French TV station TF1 were at the ready to capture it all (including from a chopper up above). Not even the team's awkward oversight of not bringing enough fuel for the attempt could stop P87 from reaching 258 mph in the hands of Francois Migault. The Frenchman was only there to watch the record attempt but, as main driver Dorchy was delayed in traffic, he duly took over driving duties.

An engine failure caused by a faulty batch of fuel from the ACO as well as a weird radar glitch in practice saw the team go back to its shop empty-handed after the race weekend in '87. But WM was back in 1988 with the P88 that, with a 3.0-liter version of the same engine, was said to crank out 900 horsepower at full boost. Again, the ACO's official radar stood in the way.

"During practice, according to the ACO radar, we never reached a speed higher than 240 mph,” recalled Soulignac. "The ACO radar system was from Metstar, a French company that supplied police radar systems. The model that was used in practice was the Metstar 206 which was sold as being able to measure speeds of up to 261 mph but we found out that it was badly affected by the vibrations caused by the high noise levels of racing cars. During the two practice days, we had discussions with Metstar about this and as a result, they told us that for the race they would bring a new type of radar system – the Metstar 208." With the new radar in place, Dorchy was free to go for the record.

First, however, the team had to effectively rebuild the car in the box because the brittle bodywork almost collapsed upon itself in unison with the engine after just a few flying laps. Three hours and 20 minutes later, Dorchy went out. He got warmed up by flying at about 247 mph down the Mulsanne Straight before finally pushing the boost all the way up for a total of 910 horsepower that translated to a top speed of 252.89 mph. In the press ads that followed, however, Peugeot boasted with a speed of 405 km/h or 251.65 mph in a bid to direct attention to the newly introduced Peugeot 405.

WM was back with the car in 1989 when Mercedes-Sauber almost nabbed the record from under the nose of the Frenchmen but the C9 could do no better than 248 mph. Soulignac thinks, though, that a higher top speed was possible with longer ratios and less downforce. After succeeding in the quest to reach 400 km/h down Mulsanne, WM again took a healthy sabbatical and only returned in 1992.

By then, Meunier had left the project and WM became WR or Welter Racing. The prototype Welter entered in '92 was heavily based upon the Peugeot 205 Spider, a lithe open-cockpit racer designed by Peugeot for its single-make series. The 205 Spider acted as the foundation for all of the WRs that followed until that faithful day in 1997 when Sébastien Enjolras was killed following a freak accident on Mulsanne caused by the single-piece bodywork becoming loose at speed.

The World Sports Car-spec WR cars were among the fastest cars ever produced under this ruleset, sometimes upsetting the established Rileys and Ferraris in the battle for pole. WR locked out the front row at Le Mans in 1995 but reliability woes, often caused by the 2.0-liter inline-four turbo engine were only solved in 2000 when WR introduced the LMP model created for the new LMP 675 class for prototypes that weighed no more than 675 kilograms or 1,488 pounds. WR kept coming back with improved versions of the LMP model but could never finish better than 19th.

The last Peugeot-engined WR was the WR LMP2, effectively a hybrid LMP 675 model modified in some key areas (such as the diffuser, the rear wing, the roll hoops, and the splitter) to comply to the new-for-2005 LMP2 rules under the 'hybrid' derogations that allowed older LMP 675 and LMP 900 cars to be grandfathered on if modified accordingly. WR did return one more to Circuit de la Sarthe, in 2010, but the WR-Salini LMP 2008 was powered by a Zytek ZG348 3.4-liter V-8.

Peugeot finally returns in full capacity and wins

It's September 23, 1990, and 1982 Formula 1 World Drivers' Champion Keke Rosberg slides aboard the sleek Peugeot 905 dressed in the unmistakable white livery made famous by the Peugeot 205 T16 Group B car. At the helm of Peugeot Talbot Sport, the Works outfit running the show, is the same man that steered Peugeot towards World Rally Championship glory, former rally co-driver Jean Todt.

Rosberg was partnered by Frenchman Jean-Pierre Jabouille making for a duo of former Grand Prix stalwarts. The 905 was one of the few cars powered by a naturally aspirated 3.5-liter engine, the others being a host of Spices fitted with the Cosworth DFZ V-8 mill. Peugeot merely took part in the final two rounds of the 1990 World Sports Car Championship as a general rehearsal prior to its full-blown assault on the 1991 season, the first to mandate the usage of 3.5-liter N/A engines derived from the ones used at the time in F1.

The FIA's decision to push for a new, more expensive, ruleset has been discussed time and again by fans and pundits alike because it triggered a knock-down effect that ultimately led to the death of the championship and the Group C formula as a whole amid the financial woes of the early '90s. Officially, the FIA tried to attract some of the manufacturers competing in the burgeoning WSPC to join F1 and thought that a good way to do it would be to impose the usage of F1 engines in place of the existing turbocharged engines and the odd large-capacity N/A ones. The existing turbo cars could still compete, but in 'Division 2' with more limitations on the maximum amount of fuel that could be used in a race and even limitations in terms of max boost pressures.

Peugeot, as a French automaker, pushed for this switch and, when it became apparent that the switch would happen, duly pieced together a program around the 3.5-liter Peugeot SA35-A1 V-10. If you remember Peugeot's tenure as the engine supplier of McLaren after Honda's sudden departure you know the Pug powerplant was far from impressive in Grand Prix terms but, in the WSPC, it was more than capable when coupled with a cleverly designed car.

The 905 in its original form wasn't that car. While it won the first race of the 1991 season, the French car was subsequently swamped by the far superior TWR/Astec-developed Jaguar XJR-14 and played second fiddle even to the finicky Mercedes C291. The first participation for Peugeot in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in an official capacity since 1926 yielded a double DNF. But, in August, at the Nurburgring, Peugeot debuted the 905 Evo 1 Bis with a completely revised aerodynamic package including a massive wing glued to the nose and a two-step rear wing akin to that used by the XJR-14.

With about 700 horsepower extracted from the V-10 engine, the new 905 (effectively, only the canopy was carried over from the original design) qualified on the second row at the 'Ring but retired. Then it scored a pair of 1-2 finishes at Magny-Cours, on home soil, and on the Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez in Mexico City. Keke Rosberg and Yannick Dalmas won in South America as Tom Walkinshaw packed his bags that contained the trophy awarded to the World Champions and announced Jaguar's exit from the series.

Mercedes too abandoned the C292 prototype slated to debut in 1992 and called it a day. Thus, Peugeot entered its second full season of competition with a reliable car and no notable competitors to speak of. Then, out of the blue, Mazda, spurred probably by its unexpected win at Le Mans, entered a Jaguar XJR-14-based prototype in the MXR-01, a car powered by a Mazda-labeled Judd MV10 engine. Toyota was the second Japanese automaker to commit to the 1992 season with the TS010, the first prototype built in TMG's base in Cologne although still run by Team Tom's. There were also some Spices, ALDs, and a pair of white Lolas to make up the numbers ut, overall, the 1992 grid was paltry. So paltry, in fact, that the championship collapsed under its own weight shortly after the 24 Hours of Le Mans, a race won, just like all others that year, by Peugeot.

In spite of the championship's disappearance, Peugeot pushed the ACO to allow for Group C cars to compete at Le Mans in 1993 as well, in order to race the 905 once again. The ACO agreed and, against a trifecta of Works Toyotas as well as some ancient Porsche 962s, Peugeot once again stole the show. it didn't even need to deploy its secret weapon, the ludicrous 905 Evo 2 dubbed the 'Supercopter' due to its UFO-like aerodynamics. Peugeot's message was now clear and, just like Matra-Simca before it, the French giant refused to build a car for the new WSC rules and quit. No privateers ever got to run the sci-fi 905 during its three-year tenure as the car to beat in the World Sports Car Championship, one so dominant that you can't help but draw parallels with Dan Gurney's AAR Eagle-Toyota Mark III that was virtually unbeatable throughout 1992 and 1993, the final two seasons of the GTP class.

Henri Pescarolo goes Le Mans racing with Peugeot power

Frenchman Henri Pescarolo needs no introduction in sports car racing circles. He'd been active in everything from touring cars to Grand Prix cars and prototypes but never put on the hat of the team boss - until 1999, that is. Previously, he'd won the 24-hour race four times as a driver as well as grabbing the French F3 title, running at the front in both F1 and F2, tackling the Paris-Dakar Rally 14 times, and becoming French helicopter champion when he wasn't flying around the world in piston-engined aircrafts looking smash some records, which he did.

In short, there was little Pescarolo hadn't done by the time he decided to run his own team, at first known as Pescarolo Promotion Racing Team, as an offshoot of Yves Courage's team. Pescarolo had previously driven Works-entered Pescarolo cars in the mid-'90s as well as being the veteran in the Elf-sponsored 'La Filiere' (FFSA Academy) Courages. He'd done most of the development work on the C41 that debuted in 1995 and this made it easy for him to get his hands on a C50 (essentially, an updated C41) for the '99 running of the race.

That first year, Pescarolo opted for the tried and tested Porsche flat-six engine, the same 935-76 3.0-liter mill with two turbochargers strapped to it that'd been around since 1976. A ninth-place finish was satisfactory but the big players began to notice Henri's efforts the following year when the trio of Sebastien Bourdais (the future CART champion and Le Mans winner), Emmanuel Clerico, and Olivier Grouillard finished a fine fourth - beaten only by the Audi steamroller. This time, the car, a Courage C52, was powered by the Peugeot/Sodemo A32 3.2-liter, twin-turbo V-6. The reliability of the French unit coupled with Pescarolo's inherent patriotism saw him stick with Peugeot power at a time when the factory Courage cars featured Judd engines.

In 2001, Pescarolo took delivery of the new C60, a clean-sheet design by Paolo Catone. Weighing in at 2,032 pounds, the C60 was quick although the Peugeot engine made o more than 550 horsepower at 6,500 rpm and 485 pound-feet of torque at 5,000 rpm due to the presence of two air restrictors. In its first year with the C60, Pescarolo undertook a grandiose program that included an entry in the 12 Hours of Sebring as well as racing in the first season of the European Le Mans Series and the FIA's Sports Car Championship. While things didn't go that well at Le Mans with only one car finishing in 13th (a second chassis was dispatched to Pescarolo Sport in time for the race in June), Henri ended the year on a high with victories in the Estoril 1,000-kilometer race (ELMS round) and the FIA Sports Car Championship round at home on France's Grand Prix track.

The following season, Pescarolo returned to the FIA Sports Car Championship with a redesigned Courage C60 that now sported a radical new look with elongated headlights a tall, bulky nose in between the fenders and openings for the brake ducts located on the inside of the wheel wells in some never-before-used low-pressure zones. Andre de Cortanze was behind this redesign and he created the Evo specifically for the Pescarolo team as the factory Courage outfit continued to run the '00 bodywork up until 2003.

Sadly, the lack of proper funding started to affect Henri's hard-working crew and the team could do no better than runner-ups in the Team's Championship of the FIA Sports Car Championship in '02 and '03 while, at Le Mans, a double finish at the bottom of the top 10 was all that was on the cards in '03. At the time, Pescarolo knew that catching Audi was hard but he could promise his sponsors a decent level of consistency in results as Pescarolo was probably the top privateer outfit along with the Dutch Racing for Holland team running the Japanese Dome S101s.

In '04, Pescarolo became the only team to try and conquer the world with the C60 chassis as the factory-backed Courage Competition stepped down to the LMP2 ranks to run and perfect the C65, a new LMP2 car heavily influenced by Catone's LMP900 design. For 2004, the denominations changed. Thus, LMP900 became LMP1 and LMP675 became LMP2. While the '04 Pescarolo C60 as it was commonly known was a further improvement from last year's car, the big difference was in the engine bay as the Peugeot engine was taken out and Judd V-10s were instead fitted.

Between 2004 and 2007, with Judd power, Pescarolo enjoyed its 'golden era': The blue/green cars with their unmistakable sweeping headlights and tall noses finished second outright in 2005 and, again, in 2006, Sebastien Loeb was part of the three-driver crew that almost beat Audi's new diesel R10. On both occasions, but especially in 2005, Pescarolo could've and - many argue - should've won the big race, giving Henri an overall win as a constructor (by now, the cars were known as Pescarolos, not Courages, due to the countless differences between the original Catone design and the updated versions that followed). Driver error and some small mishaps and mechanical gremlins stood in the way and the arrival of Peugeot in 2007 only made things harder for Pescarolo that unveiled the 01 LMP1 prototype that year, a new car for the P1 rules that was powered by Judd.

A third-place finish was the best Pescarolo could muster and things would never get better with the story ending bitterly in 2012 after the team had evaded bankruptcy once before in 2010. Peugeot might've disliked losing Pescarolo as a top-level customer but the French automaker's 'second coming' in the modern era was all that was needed to bring Peugeot back in victory lane.

The third coming of the factory is spurred by diesel fumes

Diesel had been considered for decades as a 'dirty' fuel meant for trucks, buses, or farming equipment. But, in the year 2006, our perception of the diesel engine changed. On the one hand, Audi debuted its staggering R10 TDi, a car so quiet you could hear the tires hurdling over the concrete slabs at Sebring when driving at full chat. It was also a car with well over 800 pound-feet of torque that proved effective straight out of the box. Then there was Andy Green's JCB Dieselmax, a record-breaking single-seater built to take the Diesel Land Speed Record over 300 mph. Green managed to do just that when he reached 350 mph average on August 23 2006. By then, Audi had already bagged the first win of a diesel in the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Peugeot was also preparing a diesel-powered car, the project having started in earnest in 2005 when Bruno Famin was tasked with assembling together a design team. Ex-Courage designer Paolo Catone was the Chief Designer and he, along with aerodynamicist Guillaume Cattelani, decided to go for a closed-cockpit car. The first prototype of the 908 HDI Fap was unveiled at the 2006 Paris Auto Show in September of that year, three months after the V-12 mill was showcased in the paddock at Le Mans.

Peugeot knew it'd missed the start in its duel with Audi and, as a result, the learning curve would be almost vertical given Audi's years of experience gathered while racing the R8 compared to no experience for Peugeot Sport that'd been out of the sport for the better part of 15 years. When all was ready, the Peugeot emerged as the quicker car with as much as 50 extra ponies to work with. But, of course, power is nothing without efficiency and, after all, the move towards diesel propulsion had all to do with efficiency. Audi and Peugeot realized that by making fewer stops they'd end up with a higher average speed in the 24-hour race. The key to making fewer stops, they thought, would be fielding diesel cars that weren't banned but nobody had tried to race such machines before 2006.

Peugeot's debut season was almost perfect. It won all the races of the European Le Mans Series but didn't win at Le Mans, the only race where Peugeot and Audi met that year. A P2 overall was nowhere near enough and the team came back in '08 looking for revenge. All seemed to be going blissfully for Peugeot until the rain hit. With the showers came visibility issues for Peugeot's drivers who had a hard time defogging the windows of their closed-cockpit 908s.

The Audi drivers, while drenched, had no inherent visibility problems in their open-top R10s and romped away. It must also be said that the 908 always seemed to be hampered by a narrower ideal operating window than the R10 or, indeed, the R15 and R18. In other words, it was a car that was much more sensitive towards changes in track temperature, wind, and so on and so forth. To add insult to injury, Peugeot also missed on the ELMS crown despite winning all but one of the races that season. The title slipped from under Peugeot's nose after a horrendous showing at the Sebring 6-hour season finale. Oh, and the 12 Hours of Sebring victory also eluded Peugeot that had to live with the fact that Penske beat them with a gas-powered Porsche LMP2 car.

During the Silverstone meeting in '08, Peugeot unveiled the first iteration of the hybrid-powered 908. The 908 HY, as it was called, featured a 60-kW electric motor that produced 20 seconds of power to conserve fuel on pit lane as the car would roll propelled by KERS only. Finally, in 2009, Peugeot climbed back on the top step of the podium at Le Mans. What is more, the 908s squashed Audi's new challenger, the R15 prototype, relegating it to the third and last step of the podium. A 908 also won the Spa 1,000 Kilometers but, once more, the 12 Hours of Sebring was a battle Peugeot Sport lost.

A double at Le Mans was very much on the cards in 2010 when ORECA ran a fourth 908 HDI Fap alongside the three works cars. Previously, Pescarolo had run an '08-spec 908 in 2009 but Henri's men didn't fair too well. The 2010 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans must still be a dark memory for Team Boss Olivier Quesnel. All four 908s retired with problems, three retiring in succession with seemingly identical engine failures. Hugues de Chaunac, ORECA's boss, cried tears of disbelief but he managed to better restrain himself in 2011 when, again, Peugeot was defeated.

Introducing a heavily modified version of the Peugeot 908, based on the 90X prototype, was the dominant force throughout the 2011 season of the Intercontinental Le Mans Cup (the forerunner of the FIA WEC). Powered by a 3.7-liter, diesel-fuelled V-8, it featured bigger front tires as per ACO's rules and a fin across the engine cover. But it wasn't one of these new cars that parked in Victory Lane after 12 grueling hours of racing at Sebring. Instead, ORECA's older 908 came home victorious making for quite the upset.

Then, at Le Mans, two of the three Audi R18s exited the race stage left after particularly big crashes (but both Allan McNish and Mike Rockenfeller miraculously avoided injury) leaving one R18 to fight four 908s. As night fell, the colder temperatures gravely affected the 908s pace that lost chunks of time up until dawn. Sadly, Peugeot could never make up the deficit and the lone surviving Audi won. Again, Peugeot went home with the ILMC title and many wins but no Le Mans.

But Peugeot Sport's engineers left frustrations behind and quickly began working on a new 908 hybrid, the 908 Hybrid-4. The car, still powered by the 3.7-liter engine V-8 (which was down about 150 horsepower compared to the original 5.5-liter, twin-turbocharged V-12), was unveiled at the Geneva Auto Show in 2011 and subsequent endurance tests yielded positive results. The KERS now delivered an 80 horsepower push out of corners, arguably enough to stay with Audi's R18 E-Tron Quattro and its 500 kJ flywheel accumulator system designed by Williams Hybrid Power. However, the duel never happened.

After reporting losses of about $440 million at the beginning of 2012, Peugeot decided on the spot to end all of its big-dollar motorsport programs and, obviously, the biggest spender was the FIA WEC program. The move was so sudden that the drivers were informed of the decision as they were flying to Sebring in Florida to test shortly before the opening round of the season, that year's 12 Hours of Sebring. Audi thus remained the only manufacturer in the P1 class and only at Le Mans did Toyota debut its TS030 prototype.

Since its unexpected departure from top-level sports car endurance racing, Peugeot has been tipped to rejoin a number of times over the years with the ACO particularly interested in the return of the only French manufacturer that seems to still be interested in the 24 Hours of Le Mans but the pieces of the puzzle only came together now with last week's announcement. Let's hope Peugeot's new program will herald a 'golden era' filled with battles with Toyota, Aston Martin, and the rest of the teams running hypercars.