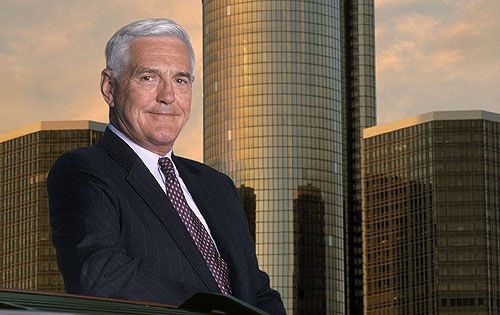

Bob Lutz was interviewed yesterday by the Detroit Free Press. He expanded on his view of GM and its future. Lutz said pretty much the same things he’s been saying for the last several years.

With one exception, and here’s that exception:

“We’re charging full-speed ahead before we know exactly what the investment is going to be, before we know whether or not we can make any money of it or not, before we know how many we’re going to sell. This is unusual. This is different from anything I’ve ever seen in my 40 years in the automobile industry.”

By way of background, Lutz told the newspaper that GM’s position in terms of product, reputation, and costs was the best it had been in 20 years. He said that both the upcoming Chevy Volt – which he promised as a 2010 model, albeit with a front end more traditionally Chevy than that of the show car – and the new Malibu were examples of GM’s new no-excuses product attitude and its engineering and manufacturing power. He called the current situation “potentially the dawning of a new era,” but said the company wasn’t there, yet.

Still, his comment was remarkable. Most companies build a product to fill a known market. Few build a market and a product simultaneously. Those who do are remarkably successful, but take remarkable risks in the process. Many who try, fail. But it is that approach which served GM well in its halcyon past, when it could set a style and create a market merely because it produced a product that created the demand.

Lutz followed up his remark by explaining his own role: “That’s why I was brought in. It’s the unleashing the engineering and manufacturing power of General Motors.”

That comment, however, omitted one important element: sales.

It takes three vocations of people for a car company to succeed: engineers, accountants, and sales people. No car company can succeed without all three. Salesmen must have something to sell, and that requires engineers to design and build it and accountants to make sure that it can be produced at a price that allows selling it for a profit.

But, it still takes someone to sell that product.

At GM, one of those three elements – engineering, finance, or sales – has always dominated the other two. Which element has been dominant has changed over time. The dominant element has, of course, tended to perpetuate its control of the company’s direction – until that element’s focus has run the company into trouble, at which point a new element has become controlling.

The pattern then repeats.

In its earliest years, of course, GM was dominated by manufacturing people, because building cars was a technological challenge. As that became less of an issue and Alfred Sloan developed the multiple brand strategy that served the company for decades, the focus shifted to sales. The 1950’s saw the company controlled by salesmen – such as Buick’s Harlowe Curtice - and the company’s success in that era is still iconic. But, the salesmen missed the economy car and, anyway, selling more wasn’t useful because anti-trust regulators were breathing down the company’s neck.

So, the company turned to engineering to get it out of the economy car hole: Ed Cole took over the GM presidency. The result was the Pontiac Tempest featuring a transaxle, the aluminum V-8 in the Buick Skylark, and the rear engine in the Corvair.

These were cars that GM’s sales people didn’t know how to sell, and that were, in many ways, solutions to the wrong problem. They were miniature cars, not economy cars. When they didn’t really solve the problem, but actually created more problems because they were not reliable, GM called in the accountants. It put Frederic Donner and James Roche into the presidency for over a decade and created one of the all-time corporate disasters: putting private investigators on Ralph Nader’s tail and having to apologize for it before a Congressional Committee. The bungling of a finance man brought down on Detroit the era of federal regulation that still threatens its extinction.

Oddly, not only were the finance men disasters as managers, they did a terrible job of tracking costs, too. At one point, GM was losing $1500 on every Lumina it built – and didn’t know it. GM bounced around looking for leaders, eventually getting to the point that it was technically insolvent.

So, what did the company do?

The same thing Ford and Chrysler have done recently: it brought in an outside guy. In this case, it was a soap salesman, John G. Smale, formerly of Procter & Gamble. If his name is unfamiliar, there’s a reason: he didn’t do much to change things at GM. He succeeded merely by keeping the company from going under. There wasn’t enough time to create a culture change.

When Lutz speaks of “unleashing the engineering and manufacturing power” of GM, he speaks of his own background and expertise. He is correct when he says that’s what he was hired to do. Lutz’ established genius is designing a car which can be manufactured at a competitive cost and will still turn out looking good. It’s no accident that Lutz’ introduction of the Malibu emphasized the cut-line on the hood. It’s his reflex.

If, however, GM is to succeed – with the Malibu, with the Volt, or overall – it is going to take more than a better mousetrap. It is going to require someone to sell that mousetrap.

It is not clear that GM has made that commitment. Devoting $150 million to an ad campaign is not the same as really selling a car. GM does not start even with the competition. Surveys have shown that most new passenger car buyers don’t even think of visiting a Chevy showroom. To change that mindset, GM needs to do more than say it has a car you “can’t ignore.”