We're in the mid-'60s when the trends amongst sportscar makers pointed towards a transition to the rear, mid-mounted layout. Lamborghini showed everyone the way in 1966 with the Miura but others had already dabbled with the idea, including small-time Italian company ATS. Others, including Ferrari, were already racing mid-engined race cars and Ford joined in on the fun with 1964's GT40. As history tells us, Mercedes-Benz wanted a seat at the table to kick back and relax away from the serious business of producing the world's best luxury sedans.

Mercedes-Benz's halo car that never was

Just like nowadays, the auto industry was evolving at a rapid pace in the '60s. New safety innovations were in the works and there were even new engine designs being looked at. German engineer Felix Wankel, for instance, had been working arduously to make his 'rotary' engine a viable option for mass-market automobiles. He'd first patented the design in 1929 but it wasn't until 1950, when NSU gave him a job and an office, that he could really build on his ideas.

Featuring a moving rotor instead of the pistons found inside the block of a classic internal combustion engine, Wankel's unit aimed to convert pressure into rotating motion and, in doing so, could brag with a more uniform torque curve and less vibration while also being lighter and more compact than piston engines.

Around that same time, Mercedes was cooking up what would later become the effortlessly gorgeous W113 SL-Class. An obvious departure from Rudi Unhlenhaut's unmistakable 300 SL, the so-called 'Pagoda' was an instant classic in its own right thanks to its clean and elegant design penned by Frenchman Paul Bracq together with Merc's safety guru at the time, Bela Barenyi, and Friedrich Geiger.

Bracq, who'd arrived at Mercedes-Benz straight after completing his military service in 1957, was the marque's chief stylist and went on to create other legendary designs such as the Mercedes 600 (W100), the Mercedes 'Stroke 8' (W114-W115), one of the precursors of the modern E-Class sedan. Bracq had readied one of the first full-body mockups of the W113 by 1961 although at that stage the car still lacked its trademark roof that gave it the 'Pagoda' nickname.

Knowing the design of the W113 was tame compared to the gull-winged sensation it had replaced, Bracq got busy drawing up sketches of a more serious-looking SL, something befitting of the marque's racing pedigree. That side of Mercedes' character hadn't been tapped on for years as the Stuttgart-based automaker pulled the plug on its ultra-successful race program in 1955 following the deadliest crash to ever occur during the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The accident, while not resulting from a mistake made by the Mercedes driver Paul Levegh, did claim the lives of many spectators and Alfred Neubauer, Mercedes' long-time 'Rennleiter' (head of the Competition department), was pressured by the management and ultimately retired together with the program at the season's end. It would take 34 years for Mercedes-Benz to return in full factory capacity at Le Mans and, in the meantime, the higher-ups frowned upon just about anything that was ostensibly sporty.

Apart from some high-output engines like the M100 6.3-liter V-8 that were meant to add even more refinement to the existing lineup of sedans, Mercedes tried to make sure no one mistook the SL for anything but a boulevard bruiser. Bracq, however, following in Rudi Uhlenhaut's footsteps, had been dreaming of a mid-engine car for a while and decided to cook one up.

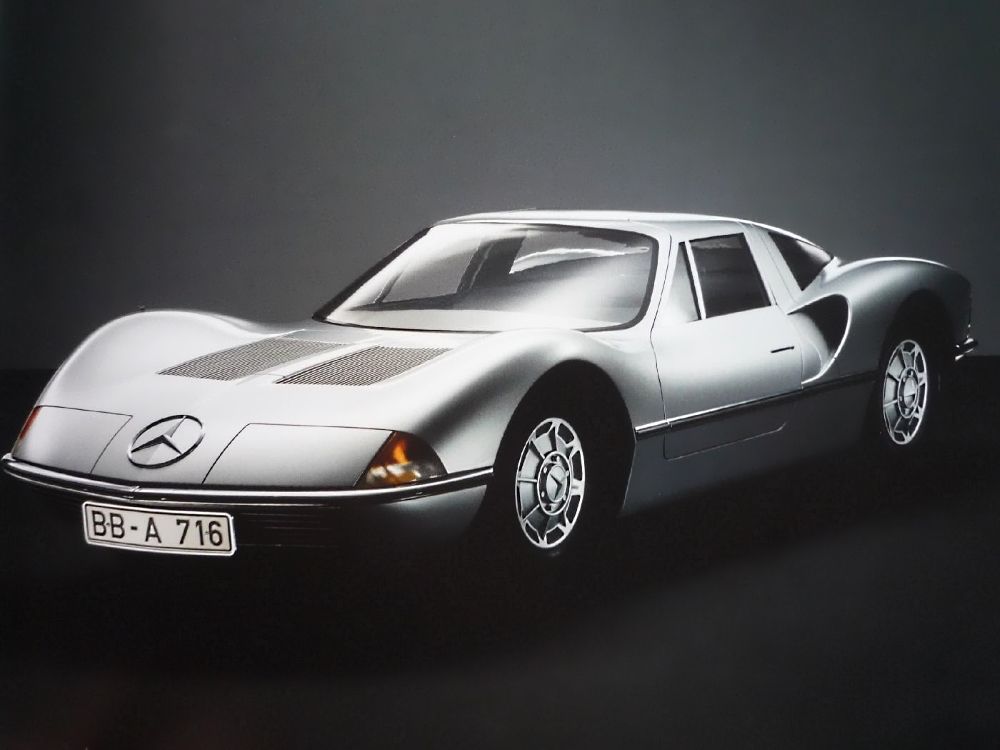

The first sketches for what would become the 'SLX' are dated May 1962 and showcase an elongated SL with a Gullwing-esque grille adorning the front fascia. A variety of other designs made it onto paper but never beyond as Bracq strives for the perfect look. A shooting brake model is also drawn up at a time when such two-door station wagons were making Chevy's Nomad especially proud.

With a low roofline and angled side windows, the shooting brake morphed into a mid-engined car, Mercedes' interests in this arena being confirmed by the acquisition of a Porsche 904, Zuffenhausen's first purpose-built, mid-engined racer. The sketches previewing the SLX showcase a decidedly Italian-looking car and that's no fluke as it was Giorgio Battistella (fresh from OSI) who aided Bracq in the design studio after joining Mercedes in 1964.

Sadly, before Bracq could think of the oily bits, the project was shelved. Fritz Nallinger, who had a leading role in the Daimler Benz Research and Development department at the time and who'd been with the company since 1922, retired at the end of 1965 and all of the pre-existing projects that were in development at the time were frozen until the new Head of R&D, Hans Scherenberg, could review them.

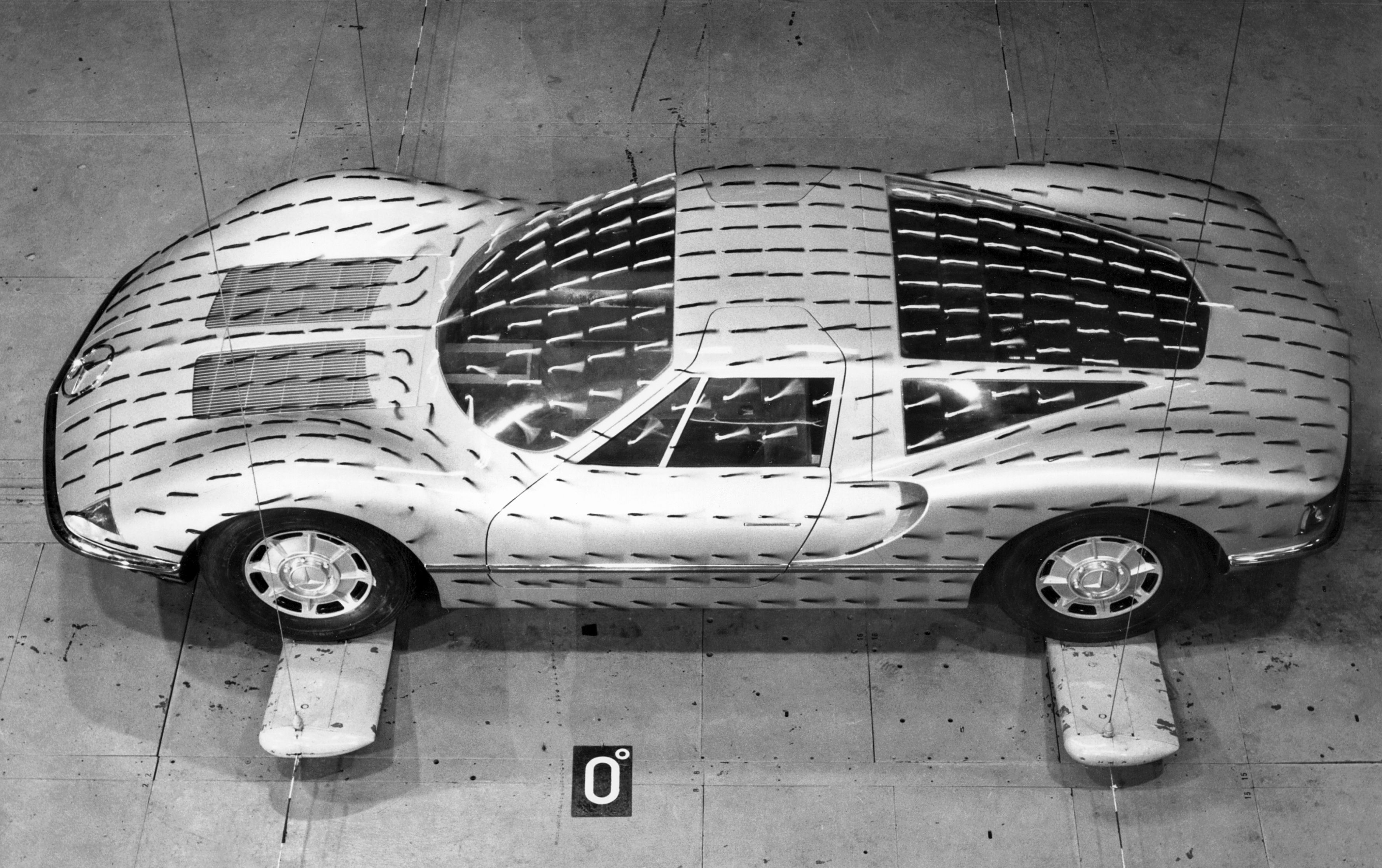

Apparently, a last-gasp attempt to help the board entertain the idea of a mid-engined halo car took place in 1966 when a full-scale wooden model was built. The model featured no interior and nor were there any details about an engine. Sadly, those in charge were less than satisfied with the appearance of the SLX and Bracq had to move on to bigger things, namely sedans. Perhaps the results of at least one stint in the wind tunnel didn't help either.

What happened next

While nothing came of the SLX, the elegant design study did influence a string of mid-engined sports cars that Mercedes would begin building towards the end of the '60s. Remember that Wankel license bought by Daimler in 1961? Mercedes tried to build its own Wankel engine with the initial iteration being placed in the W113 SL around 1968.

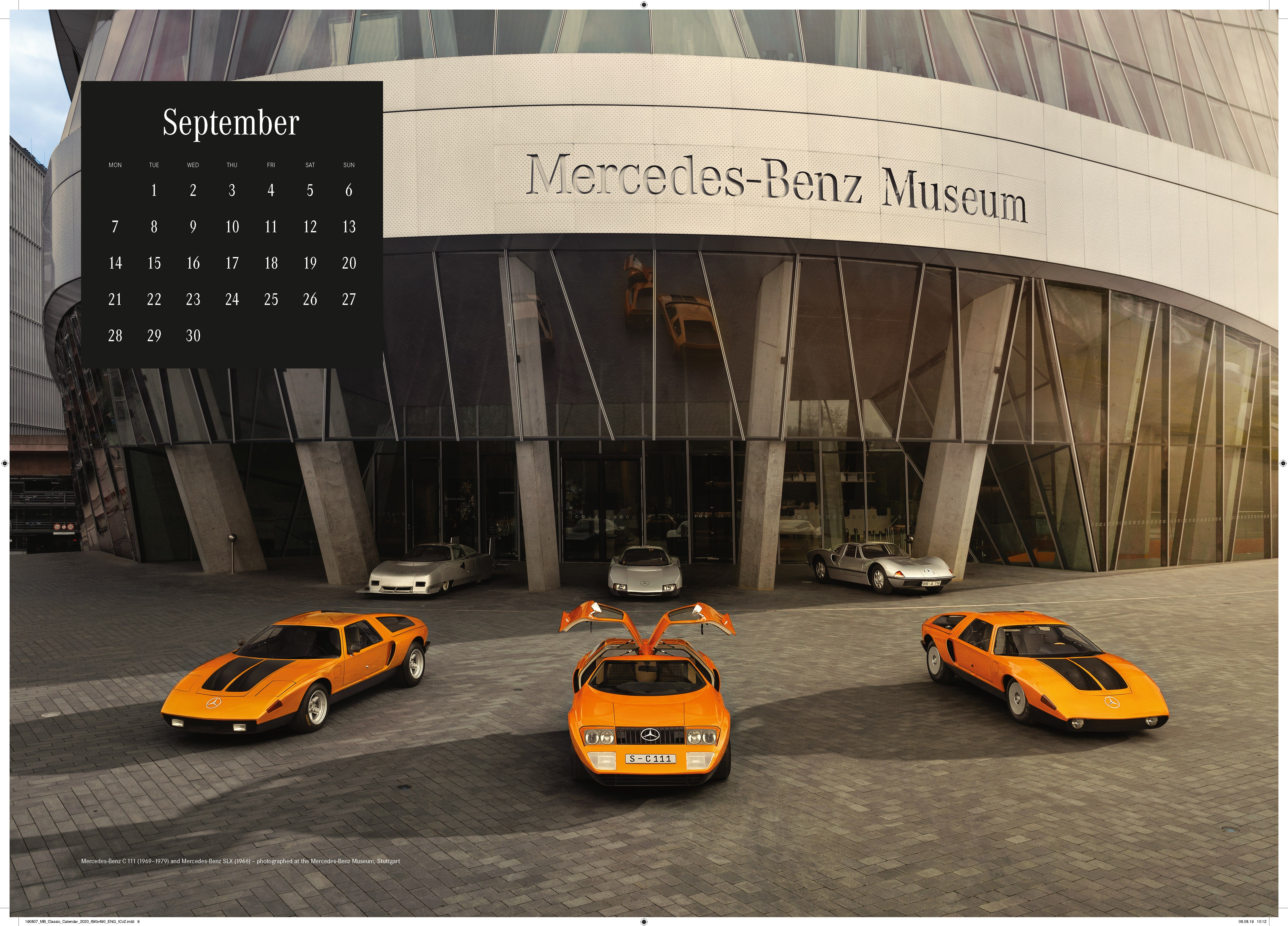

More work was needed as the unit barely developed 220 horsepower and thus the C111 program was born. Affectionately known as the 'Tin Box', the C111/1 was unveiled in 1969 and was the brainchild of Mercedes' team of engineers and designers at Unterturkheim. The design of the C111/1, as well as its two brothers, is largely credited to Bruno Sacco who was the company's No. 2 stylist after Bracq.

Sacco was perhaps inspired by the SLX, designed by Bracq and Battistella at Sindelfingen, but he did not have a hand in its design. In spite of what, in 2010, when Mercedes-Benz organized an exhibition revolving around its mid-engined design studies, the SLX was referred to as the 'Sacco Study'.

This shows just how little is really known about the SLX, a car so mysterious that even its parent company got its genealogy wrong at one point or another. In any case, Mercedes-Benz decided not to put the Wankel-engined C111 into production, nor would they budge at the sight of the C112, a spawn of Mercedes' involvement in the World Sportscar Championship almost 30 years after the birth of the SLX.

With the impending (we've said that a few times before already, haven't we?) arrival of the AMG One, Mercedes-Benz is set to finally amend its relationship with mid-engined sports cars and we hope, as ever, that the company's most ambitious sports car to date will also be the inspiration for a race car. After all, the SLX too should've seen the race tracks had it receive the green light.