The Chrysler Airflow was supposed to be Chrysler's forward-thinking hit that would re-write the book on automotive styling and, in the process, teach people that an aerodynamic car is the way to go. Only it didn't. All that the Airflow did do was to buck the trend and almost tanked Chrysler. With its steel body and fountain-esque grille, it shocked customers rather than appeal to them but now, 86 years since its release, it's universally accepted that the Airflow is among the very first mass-produced aerodynamic cars in the world.

A hard-selling slippery car

It was in the late '20s that Carl Breer, one-third of Chrysler's "Three Muskateers", the trifecta of brilliant engineers that effectively put Chrysler on the map from an engineering standpoint, began thinking about the possibility of building an aerodynamic road car. By then, a few engineers had given teardrop-shaped vehicles a shot but not even the genius that was Ferdinand Porsche could push his ideas onto the table of a major automaker and into series production.

Breer knew that just about the only thing that was designed to cut through the air with minimum fuss was an airplane so he and his colleagues, Owen Skelton and Fred Zeder, contacted aeronautics pioneer Orville Wright and asked him for help. With Wright's aid and the blessing of company owner Walter P. Chrysler, a rather basic wind tunnel was conceived and built in Ohio and that's where the shape of the Airflow was born.

A mule, nicknamed the 'Trifon Special', was ready by 1932 and, two years later, the production version of the Airflow was ready. As a semi-hatchback, full-size sedan, the Airflow stunned crowds at the 1934 New York Auto Show where in excess of 18,000 orders were taken for the breakthrough model.

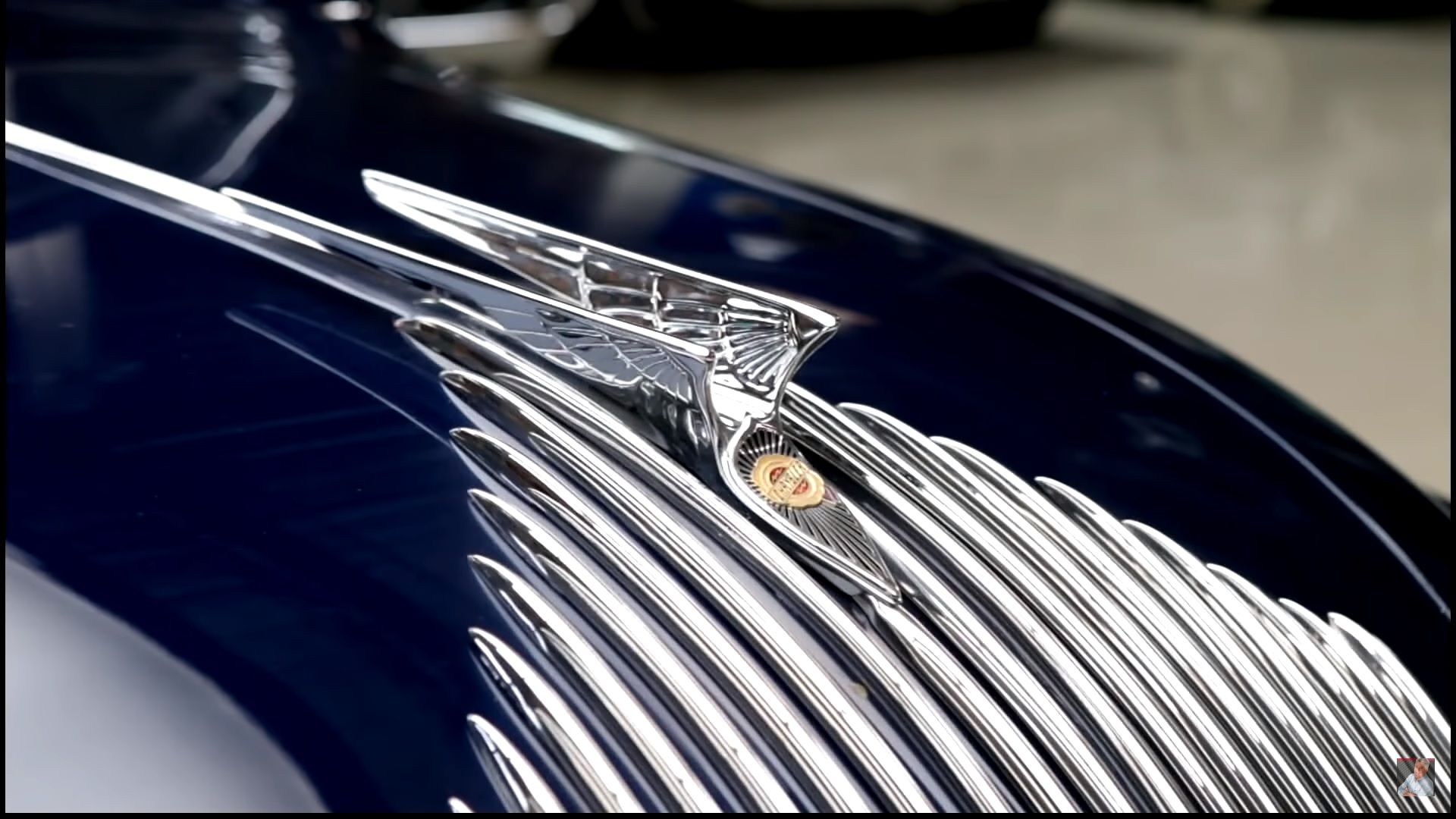

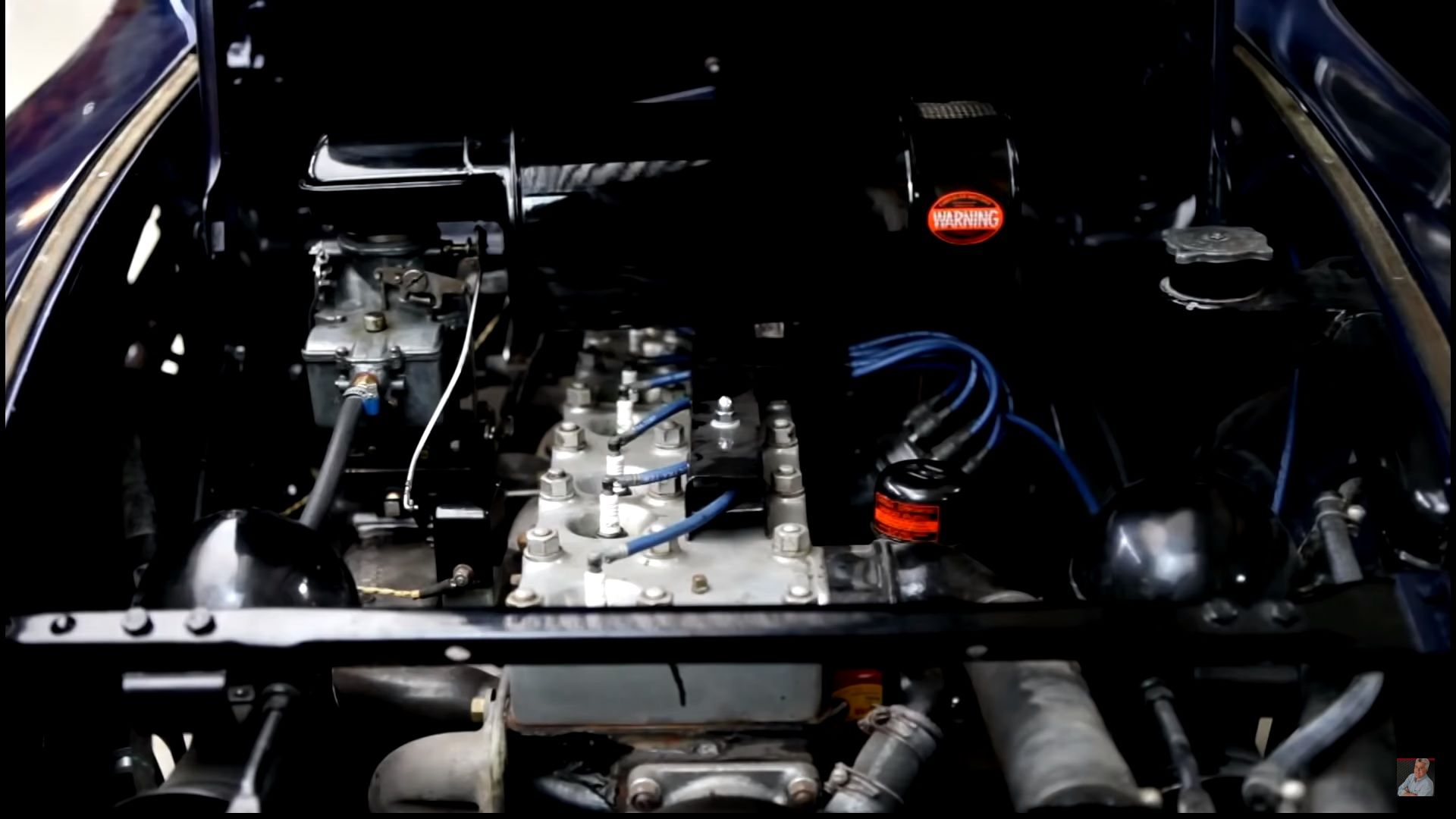

Bearing design strokes by Oliver Clark, the Airflow featured a huge, multi-bar grille as well as twin headlights that were incorporated in the fenders. Also taken from the 'Trifon Special' was the seating position with the seats in between the axles for added comfort and the position of the engine atop the front axle to increase interior legroom in the front and reduce heat transfer.

In spite of the Airflow's clever features and Walter P. Chrysler's conviction that it was the door-opener for "a whole new trend in personal transportation," things soon took a turn for the worse. Rumors spread about the unsafe nature of the car's all-steel frame and, to add insult to injury, this innovative structure caused delays in production that resulted in people canceling their orders and either purchasing the more traditional Chrysler Airstream or defect to other manufacturers altogether.

Chrysler offered the Airflow in four 'flavors', Jay Leno's example being the ultra-rare Imperial CX (one of three in the world, according to Leno), which was the second most expensive trim level and, as such, the second biggest Airflow available.

While the Airflow was heavier by several hundred pounds than the more traditional-looking Airstream models that were powered by straight-sixes (just like the DeSoto-badged Airflow models), it was capable of effortlessly reaching 90 mph.

The performance, however, didn't help increase the Airflow's mass appeal. If 45% of all new Chryslers sold throughout 1933 had been straight-eights, that percentage dropped to 31% in 1934 when the Airflow was introduced. Moreover, the six-cylinder Airstreams easily outsold the Airflow and rival company Oldsmobile recorded an impressive 128% sales gain across 1934 alone.

With a 146.5-inch wheelbase, the Airflow CX rivalled Cadillac's V-12 models and this was noticeable from the price point as well. For instance, the hand-built, range-topping Airflow Imperial CW with its 150 horsepower flathead sold for $5,145. $350 more than the comparable Cadillac at a time when you could buy a house for about $5,500. Little more than 10,000 Airflows were sold in the car's first year in production but that figure was down to 4,603 units in 1937, the Airflow's final model year.

Years later, with mileage and efficiency becoming increasingly stringent matters for each and every automaker, the issue of designing a car with a reduced drag coefficient became paramount - confirming Walter P. Chrysler's intuition that the Airflow represented the future. Chrysler's misfortune was, though, that it'd brought the future too soon for the people to fully embrace it.