Mercedes is certainly no stranger to motorsports. The German brand has been at it for the better part of the last 100 years. The company was involved in Grand Prix as early as 1923, with their teardrop-shaped Benz Tropfenwagen and then there was LeMans incident from 1955 where a 300 SLR crash-landed into the stands. Mercedes dominated the FIA GT1 class in the 1990s, but that was followed by some interesting developments with their Mercedes CLR, which apparently acted more like an airplane rather than a car. As a result, it managed to flip, and not just once.

What is the Mercedes CLR?

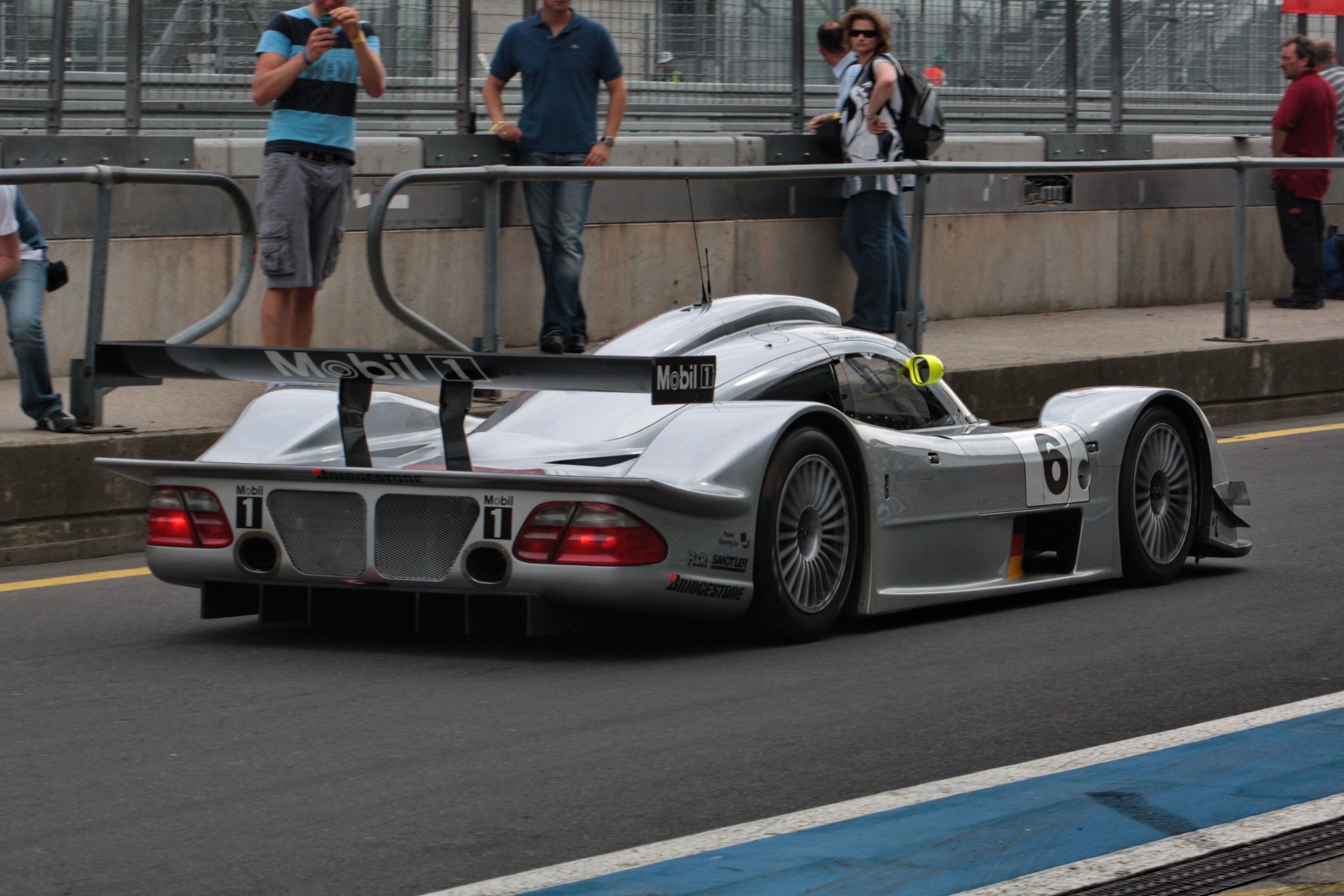

The CLR is a successor to the Mercedes CLK GTR, which enjoyed great success in the FIA and LeMans GT1 class. The car was built by HWA RACELAB – a well-known manufacturer of AMG components, also based in Affalterbach. The Mercedes CLR was designed specifically for the LMGTP (LeMans GT Prototype) class. LMGTP cars were loosely based on road cars – in this case, the Mercedes CLK – but were too radical for road use.

LMPGT was unique in that they were specifically designed for the LeMans race and did not need to consider a wider championship. The Mercedes CLR was essentially an even more radical CLK GTR, dedicated to racing at the LeMans racetrack.

Why Mercedes developed a LeMans-specific car?

Mercedes took great pride in their racing heritage. Despite dominating the FIA GT1 class, they experienced severe technical difficulties during the 1998 LeMans race, which resulted in all of their cars being retired relatively early in the race. For the 1999 race, they came up with the CLR – an evolution of their CLK GTR.

It flipped on three occasions

The first flip happened on a Thursday, during qualifications. Mark Webber was driving a number four CLR.

Three Mercedes CLR cars managed to get into the top 10 of the starting grid. Position four was the CLR driven by Pedro Lamy, Bernd Schneider, and Franck Lagorce. Position seven was taken by the car driven by Nick Heidfeld, Christophe Bouchut, and Peter Dumbreck. Position 10 was taken by the AMG Mercedes car driven by Marcel Tiemann, Mark Webber, and Jean-Marc Gounon.

Maybe there was a behind-the-scenes dialog between Mark Webber and the engineers, in which Mark said “I want to fly over the circuit”, to which the engineers replied, “We can make that happen”.

Despite the obvious problem, Mercedes still entered the race. Five hours in, on lap 75 Peter Dumbreck in the number five CLR flipped while chasing a Toyota TS020. There is a video showing how the car flips three times, then landing in the threes just outside the racecourse. It’s worth noting that none of the “take-offs” caused any serious injuries to the drivers. Peter Dumbreck’s “flight” finally persuaded Mercedes to retire from the race.

What caused the CLR’s desire to fly?

Mercedes simply pushed the design of the car too far, causing the lack of aerodynamic stability. This the way a moving car reacts to changes in the air, caused by other passing vehicles in its immediate vicinity. There are a few design elements that contribute to the car’s aerodynamic properties that caused it to take flight.

Circuit de la Sarthe is a very demanding circuit, testing all aspects of the car – engine, suspension, brakes, and aerodynamics. A car designed to tackle this circuit must be slippery enough to achieve high speeds and produce enough downforce to handle the technical sections. A high speed requires low drag, but high downforce also comes with more drag. You can see how balancing the two can be tricky.

Large Overhangs

While the CLR was as long as legally possible, at 4,890 mm (192.5 inches), the wheelbase was shortened to 2,670 mm (105.1 inches). The idea was to maximize the car’s overhangs, on which they can add more aero. On paper, this means you can have bigger front and rear diffusers, as there is simply more bodywork to accommodate them.

This increases underbody downforce, which essentially adds much less drag, thus allowing the “Merc” to reach very high speeds on the straights. Long overhangs, however, make the car more prone to rocking backward and forwards.

Pitch-sensitive

In order to reduce the over-body downforce even further, Mercedes almost neutralized the pitch angle. Race cars usually run a negative pitch angle, which dictates how much lower the front is to the ground, compared to the rear. Doing so increases downforce, but also generates more drag. Most cars have a pitch angle of -2.5 degrees. Mercedes, however, reduced it to -0.7 degrees.

Doing so, resulted in the CLR’s front end losing downforce, which in turn makes it easier to generate front-end lift. Couple that to the short wheelbase, in relation to the full length of the car, and you get a very pitch-sensitive car. Under braking, the front would dive more, while under acceleration, the rear will be more prone to squatting. Moreover, terrain modulation and road imperfections would unsettle the pitch of the car, disrupting the airflow.

The Indianapolis corner

Webber’s crash happened at the Mulsanne straight, on the way to Indianapolis corner. The section was known to be notoriously bumpy, but that wasn’t the whole reason for the flip. Webber’s CLR was in the slipstream of the car in front, which would have disrupted the CLR’s front-end downforce. Combined with the bumps on this section, the car became even more pitch sensitive. As the pitch angle changed to +2.0 degrees, due to the rocking, the car not only had close to zero downforce, but it had actually started generating lift.

On top of that, the cockpit of the car had a lift-generating shape, which the rest of the car was supposed to counter. This moves the air pressure center towards the front and at one point the generated front-end lift becomes more than the rear downforce. A +2.4-degree pitch angle was the breaking point at which the car flipped. What aided the car’s take-off was that it happened on the crest of a hill, while following the car in front, thus dramatically changing the car’s pitch angle in relation to the road.

The CLR’s airplane-like behavior brought changes

After the third flip, Mercedes withdrew from all its 1999 racing programs. The brand is yet to return to LeMans. A.C.O. (Automobile Club de l’Quest) – creator and organizer of LeMans, decreased the maximum allowed overhang length, for LeMans entries, and decreased the hill on the Mulsanne straight by eight meters (26.24 feet). They also smoothed out the bumpier sections, to reduce the risk of front-end lift.

Although spectacular to look at, it’s hardly a treat when you’re in the cockpit of a race car that suddenly wants to become an airplane and fly into the French skies.