The BMW M1 remains the only true supercar built by BMW and, thanks to the Procar Series that celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, it enjoys an aura quite like no other supercar. Harald Ertl, the mustachioed Austrian journalist who split his time between writing and racing, decided he liked the sound of "Harald Ertl the Land Speed Record holder" and prepared for the job of creating the most insane M1 seen outside of the racing circuits.

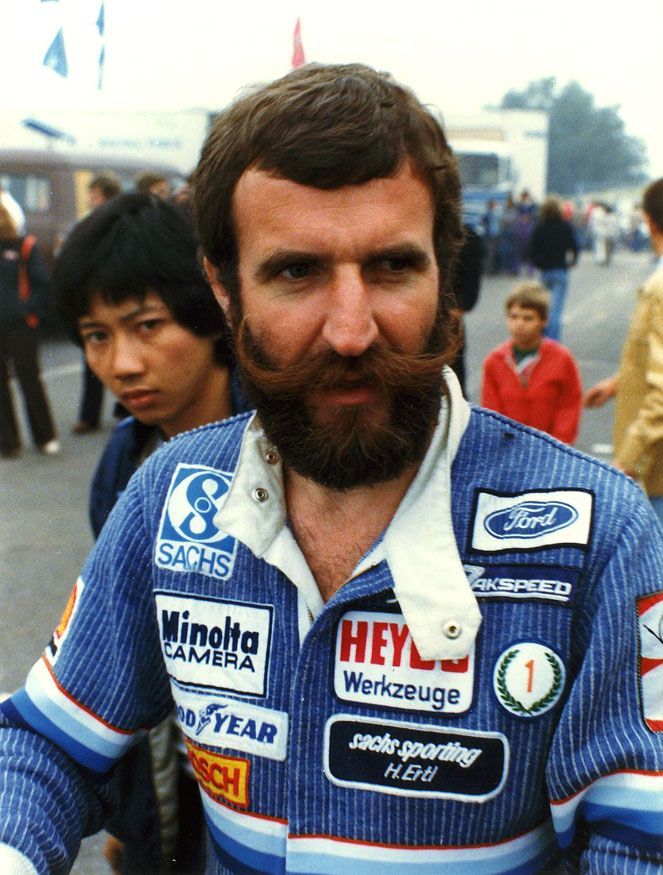

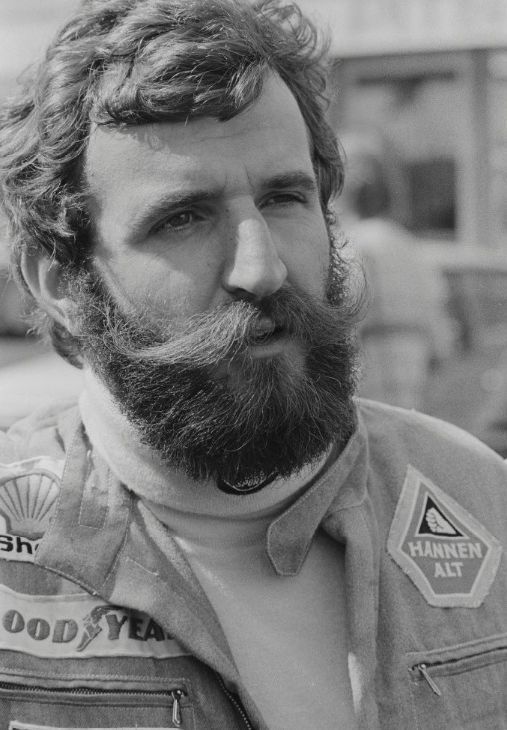

Ertl. Does this name ring any bells in your head? If you are, by chance, or at least used to be a model car aficionado, you might remember the venerable Ertl plastic and die-cast kits. Well, this Ertl has nothing to do with the American toy company because Harald Ertl was Austrian, born on the last day of Summer in 1948 in Zell Am See, a picturesque town in the state of Salzburg. By trade, he was an automotive journalist but, as time wore on, he became more and more involved in racing cars rather than merely testing and writing about them - a bit like Frenchman Paul Frere. Ertl established himself throughout the '70s as an easily adaptable semi-professional driver who could tame anything from an F2 single-seater to the menacing Zakspeed-built Ford Capri III.

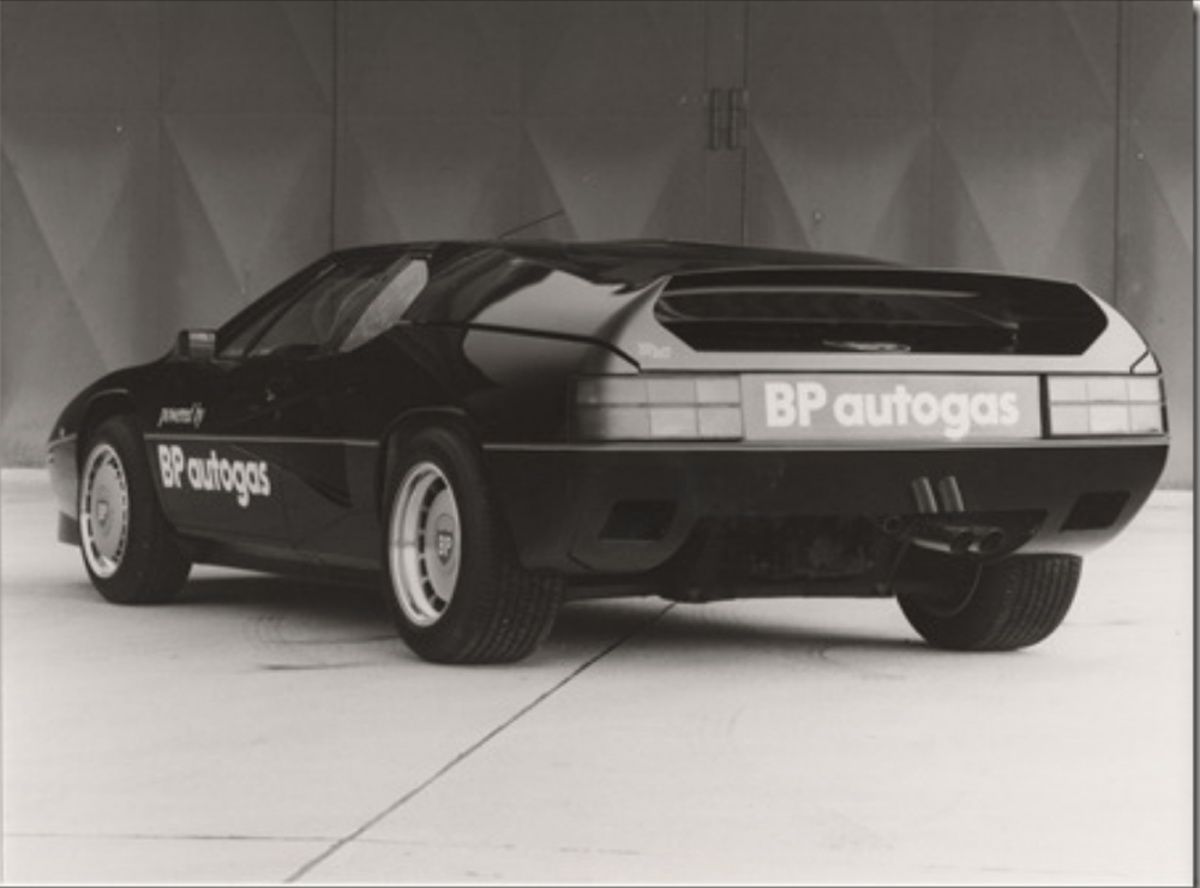

In 1981, he took a sabbatical away from racing and, instead, focused on getting his name carved in the history books as a land speed record holder. His weapon of choice? A twin-turbocharged BMW M1 with a bespoke widebody and about 400 ponies at the crank. Due to the lightness of the thing, the same output you'd find hiding under the body of a Genesis G80 propelled Ertl to a top speed of 187.3 mph. The trick up Ertl's sleeve was to be found in the tank of the M1. You see, the car was made to run on liquid petroleum gas (LPG), also known as Autogas. No one before Ertl had gone that fast in an LPG-powered car and, in a way, it's fitting that the current fastest LPG-powered car is also a BMW, only one that tops at almost 207 mph.

BMW, a brand much bigger now than it was 40 years ago

BMW is one of the world's leading premium automakers. Today, the Munich-based company employs some 11,000 people in the United States who build the growing number of SUVs part of the X series. As of 2015, over 400,000 vehicles with the white, blue, and black roundel on the hood were made Stateside and, currently, BMWs are being sold through 300 different suppliers in the U.S. alone.

Why is all of this relevant? Well, I'm trying to paint a picture that depicts BMW's size as a manufacturer, a manufacturer that sold over 310,000 cars in 2018 in the U.S., being edged out in the end by Mercedes-Benz by the slimmest of margins - there are some 4,000 cars more in Daimler's bucket thanks to record sales of the GLC. But, BMW wasn't as big in the '70s. Take 1976, for instance, when BMW sold little more than 26,000 cars over here. At that time, only 0.2% of the American population was buying a BMW despite the fact that the company was already established for its well-built, fast, and good-looking models that had an edge on Mercedes-Benz when it came to performance.

In spite of this, BMW was solely known for making sedans and the odd convertible. They were not known for making sports cars until that same year, 1976, when the 6 Series entered production. Truth be told, at the time, the really fast two-seaters were solely coming out of Italy with Maserati, Ferrari, or Lamborghini being the ones immortalized for teenagers to have something to adorn their bedroom walls with.

How the M1 came to be and why it failed at its job

Jochen Neerpasch, fresh from his tenure as the Head of Motorsports at Ford Germany in Cologne, joined BMW in 1972 with a plan: to create a racing division at BMW too, one that would be bigger and better than what he'd masterminded at Ford.

The E9-based CSL proved to be a reputable racer and, in its first year of competition, the German steamroller crushed even Frank Gardner's Camaro that was usually the ruling force in the British Saloon Car Championship (BSCC) as Derek Bell and Harald Ertl both won their respective heats in an Alpina-entered CSL to conquer the legendary Tourist Trophy at Silverstone at a record pace. You'll see further along in this story that this victory had an effect on Ertl but, first, on with the M1.

At that point, Neerpasch realized that a replacement for the CSL was badly needed, and it had to be something quite special to take on - and beat - Porsche. The problem was, he didn't have a car. The Group 5 CSL was homologated and raced thanks to the fact that BMW made enough road-going CSLs to enter the Group 2 version in '73.

Neerpasch found Bracq's mid-engine concept collecting dust at BMW's headquarters and thought this is the way to go. After all, Porsche was battling hard with its rear-engine configuration, and a mid-engine car would be superior from the get-go to anything Porsche had up its sleeve. But BMW didn't have any knowledge in building a car with the engine positioned behind the cabin, so Lamborghini was hired to help with the project. As Car & Driver puts it, "Lamborghini’s financial problems postponed the start of production beyond the original 1977 deadline," and this saw BMW return to its line of sedans in search of a new contender in Group 5 as the CSL had to be put out of its misery. The unassuming E21 was considered worthy enough to be transformed into a Group 5 warrior. Again, most were fitted with the legendary inline-six unit while only a select few received turbos (like the one raced Stateside by David Hobbs which had its engine tuned by McLaren).

Sadly, this process didn't progress as quickly as BMW hoped and, in July, Neerpasch announced that BMW struck a deal with the Formula One Constructors' Association (FOCA) to stage a single-model support series prior to each Grand Prix beginning in 1979. The series became known as Procar and almost all of the F1 drivers on the grid at the time - as well as some BMW devotees outside of F1 - raced in the series, minus Ferrari's Jody Scheckter and Gilles Villeneuve who didn't receive the green light to battle the rest of the guys in - not 100% - identical machinery from The Drake.

As exciting as the series was, it only lasted for two years by which time BMW was still not done building those 400 road-going M1s to homologate the racing version. Neerpasch's dream to take on Porsche at Le Mans and beat it at its own game turned into a bit of a fiasco as the boys from Zuffenhausen packed their bags and left the World Manufacturer's Championship at the end of 1978. Still, the 935 remained relevant, and it even won the 24 Hours of Le Mans overall in 1979.

That same year, Lancia, who managed to react quicker than BMW, debuted the Beta Monte-Carlo Turbo which went on to become what the M1 should've been - a world-conquering, 935-beating race car with the engine in the middle. In fact, the Beta won the World Manufacturer's Championship three years on the trot: once in the secondary division of Group 5 for cars with engines up to 1.5-liters and twice overall.

Around the time the first M1s started to compete outside of the Procar series, an Austrian with a flamboyant mustache full of wax that complemented a full beard started to draw up plans for a daring attempt: to beat an under-publicized land speed record, one for cars powered by LPG. The man was Harald Ertl, the same Harald Ertl that had won the Tourist Trophy in 1973 aboard a Jagermeister-sponsored CSL.

Who was Harald Ertl?

I hear you asking, "Why Ertl?" What was it about this throwback-looking Austrian that made him fit for the job? Well, it was his idea, to begin with, and he also had the means to fund the whole gig. He also knew his way around a fast car since he'd driven a few F1 cars in his career as well as some Group 5 BMWs and Fords.

According to GP Rejects, his 1975 season wasn't stellar but he racked up one podium finish, and this was enough to motivate Ertl to move up to F1. But even then it wasn't easy to get into the World Driver's Championship and he asked former F3 rival James Hunt for an opinion on the matter. Hunt suggested a second season of F2 would be the best idea but Ertl had none of it. He tried to buy a car from Surtees, then from Williams and, later, when "the 308’s price was hiked after Hunt’s Dutch Grand Prix win," he decided to ring Bernie Ecclestone's doorbell. The future F1 supremo was open for business, and he duly sold Ertl a Hesketh 308 with the condition that he'd pay for it in cash which he did since he'd struck a sponsorship deal with German beer maker Warsteiner.

Mattijs Diepraam wrote the following for 8W about Ertl's tenure in F1: "As far as his F1 record is concerned, three abysmal years with a Hesketh team very much on the decline made him into the Piercarlo Ghinzani of the seventies."

All this would have you think Ertl was mediocre at best and, indeed, he was no professional having started out as a journalist right after graduating before he even sat in a racing car. He kept writing about cars and racing throughout his career, and he never earned a living by putting his helmet on and buckling up in a race car. Having said this, very few drivers were able to make ends meet just by racing in the '60s and '70s. But, if you want to see the best Ertl had to offer, you have to look at his GT and touring car record.

He consistently switched his attention between F1 and other forms of racing and even shaved his signature beard after winning the Tourist Trophy in 1973 - although no images exist of a clean-shaven Ertl. The victory awarded him a factory drive in 1974 but his attack on the ETCC that year didn't amount to anything.

He competed in Division II with a Rodenstock-sponsored BMW 2002 Turbo until the team struck a deal with Toyota Deutschland who was eyeing the series for a while and had a Celica TA22-based Group 5 car ready for Harald to drive. He duly won the non-championship ADAC Trophy in Zolder but the car was troublesome and didn't finish too many races. In 1978, with backing from Sachs Sporting who'd been with him in F1 as well, he raced a BMW E21 Turbo. With five wins under his belt in Division II, he took home the title. What's interesting is that the Division I folks racing in Porsche 935s and other more powerful Group 5 machinery ran in separate races to the Division II gang, but the whole bunch was fighting for one overall title which makes Ertl's achievement that much more impressive. It wasn't until 1980 when Hans Heyer won the title in a Fruit of the Loom-backed Lancia Beta Monte-Carlo Turbo that a Division II driver won the title in DRM. Charly Lamm, the late great Schnitzer team boss, then only a student, helped mastermind Sachs Sporting 1978 campaign.

In 1979, the Sachs Sporting team updated to a Zakspeed-built Ford Capri III equipped with a 1.4-liter, inline-four with a single Borg-Warner turbocharger strapped to it. Ertl won two races and even experienced driving a wacky Lotus Europa-based Group 5 car that was no good. In 1980, he won four times and finished third overall in the DRM race held at the Donington Park track in the U.K. At the end of the season, Ertl decided to focus solely on his journalism work but, in fact, the plans to build a land speed record car were afoot.

The BMW M1 that was faster than a 1980 Formula 1 car

In standard trim, a BMW M1 sported a DOHC, 24-valve, 3.5-liter, inline six-cylinder engine that produced 277 horsepower at 6,500 rpm and 243 pound-feet of torque at 5,000 rpm.

Of course, setting a record would definitely raise awareness to the new product and this was exactly what BP was hoping to see happen as the M1 went through a serious makeover to be fit for the job. Gustav Hoecker's Sportwagen-Service took care of the engine which received two Borg-Warner turbochargers for a final output of at least 410 horsepower - about as much oomph as the Sauber-built Group 5 M1.

The body also received a Group 5-inspired widening kit apparently designed by former Formula 1 team owner Walter Wolf while new Sachs springs were attached to the chassis originally designed by Gian Paolo Dallara at Lamborghini.

There's a silver-lining to Ertl's record, though. As Hemmings reports, "Ertl’s record run came without FIA sanctioning or supervision, and thus never made the record books. Perhaps it was a dry run of sorts, with Ertl intending to back it up with an official pass later on, as long as the sponsorship money remained available." Sadly, BP soon quit the project and Autogas went on to fuel heaters and other home appliances.

Now in pure barn find condition, Ertl's land speed record M1 has spent its post-record years lacking the care it deserves. It was even damaged in 1988 when in the ownership of Dutch Alpina dealer Piet Oldenhof, the fender-bender proving quite serious since the M1's M88 engine had to be changed. That same year, Oldenhof sold the car to some Japanese inventors but, five years later, it appeared up for grabs in the U.K. That's when pharmacist Pummy Bhatia bought it. Bhatia died just two years later and his family had trouble taking care of his car collection, the BMW M1 often sitting outside at the mercy of the elements. Even the Midlands Motoring Museum, which borrowed the car from Bhatia's family for a while, kept the car out in the cold.

Yes, Harald Ertl is no Ayrton Senna, and he isn't even an equivalent of Paul Frere in the small world of journalists who turned to motor racing but he was no slouch behind the wheel, and he showed that he was fearless not only behind the wheel of the LPG-powered M1. He was also one of the four drivers who rescued Niki Lauda from his fiery wreck during the 1976 German Grand Prix and, in many people's eyes, this is Ertl's only claim to fame. If nothing else, I've tried to shed some light into Ertl's career with this article to prove that he was more than "the other Austrian who helped save Lauda's life".

Further reading

Read our full review on the 1978 - 1981 BMW M1.

Read our full review on the 1979 BMW M1 Procar Restored By Canepa.

Read our full review on the 2008 BMW M1 Hommage