In 1965, Ford won the World Manufacturer's Title in the GT ranks with the Cobra Daytona Coupe. But you wouldn't have found the aerodynamic Kamm-tailed endurance racer on almost any bedroom wall around that time. Instead, everyone was hooked on Shelby's new roadster - the Cobra 427. Sporting the 'side-oiler' big block 7.0-liter V-8 good for at least 500 ponies, the revised Cobra was five inches wider than the AC Ace-based examples before it, handled slightly better due to an all-new chassis with independent suspension, and was one of the fastest cars you could register in 1965. With a 0-60 mph time of four seconds flat and tires that would go alight at the lightest depressing of the gas pedal, the 427 was unruly but that's what made it a legend.

Think about what American cars you have loved throughout your life. It's almost certain that the Cobra 427 was (or still is) in amongst your favorites. With rounded, flared arches, a gaping mouth and a scoop on the hood, and a pair of racing stripes traversing the (usually) blue paintwork, the baddest Cobra found its place in the history books from the moment it entered production. It was as loud as a pack of lions - if lions were ever to attack in packs - and more unruly than a teenager who's going through a phase that's "totally not a phase". The first 50 cars made were Competition or Semi/Competition-spec while the other 260 copies built until late '67 were tuned to be more street-oriented, although even this can be considered a stretch. That's why probably no other car can boast with such a wide variety of replicas quite like the Cobra and, naturally, most try to copy the look of the Cobra 427.

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra

- Make: Array

- Model: 1965 Shelby 427 Cobra

- Engine/Motor: V8

- Horsepower: 450 @ 6000

- Torque: 480 @ 3700

- Transmission: four-speed manual

- [do not use] Vehicle Model: Array

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra Exterior

The Shelby Cobra is one of those cars that need no introduction. You can be an avid gearhead or just another passersby lacking even the slightest interest in cars, it doesn't matter, upon laying eyes on one you will stop in your tracks and look. And then look some more. It doesn't even matter if it's a dubious replica with oversized chromed rims with fake knock-offs. The reason is simple: the Cobra looks achingly good from just about any angle and the wide-fendered 427 is an even bigger visual delight, sending shivers down the spine of anybody whose heart is still pumping. Of course, you can argue that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but we're yet to see someone fault the Cobra's styling.

It all began in 1961, shortly after Carroll Shelby took the decision to hang his helmet up after years of racing at the highest level in both long-distance endurance races and Formula 1 despite suffering from heart problems since he was a child - that ultimately culminated with an angina pectoris diagnosis when he was busy wheeling Maserati's Birdcage for Frank Harrison.

Freed up from any racing commitments, and not eager to go back at any of his past jobs that included driving a dump truck, Carroll was ready to work towards a dream that'd been haunting him for years: that of building a car bearing his own name. Years later he'd often say that the only reason he picked up racing at all was to learn how a team works and what you need to do to end up with a winning automobile, lessons he'd later apply when he himself would start climbing the steep mountain towards success as an automaker.

He first moved to California to act as a tire distributor for Goodyear. From there, he started looking for a foundation that would be the starting point of his new car, the Shelby. It's unclear how Carroll, then aged 38, got the idea of stuffing an American V-8 in the lightweight chassis of a European two-seater, but he wasn't the first to put it into practice. Briton Sydney Allard outfitted his Allard sports cars with American V-8s as he reckoned local engine options were tepid and less reliable than American ones.

Shelby, however, was considering another British sports car for his hybrid of sorts: the Austin-Healey 3000. Launched the year that the Texan won Le Mans outright in a works Aston Martin, the Healey 3000 came from the factory with a 3.0-liter BMC C-Series engine good for 136 horsepower. This powerplant would become the disposable part as Shelby hoped to cram in the engine bay a 4.6-liter Chevy V-8. Zora Arkus-Duntov and other top suits in Michigan were always going to be against a carmaker buying GM units to power something that could outgun the Corvette so no hands were shook and Shelby had to regroup.

As luck would have it, he eventually found out that A.C. Cars of Surrey, England, was in trouble as its supply of BMW-derived Bristol 2.0-liter inline-sixes had been halted. The Ace, a 1,920-pound sports car proved mighty on both sides of the Atlantic in its day, winning the 2.0-liter GT class at Le Mans in '59 as well as a sleuth of SCCA divisional titles around that same period. But, by '61, the car was feeling a bit long in the tooth with its leaf-spring rear suspension and dual-tube chassis, never mind the antiquated engine that was, originally, a pre-war BMW design.

Using his natural business acumen, Shelby stepped in to help - both himself and AC Cars - by brokering a deal between the British low-volume automaker and Ford Motor Company who'd supply the engines. The Blue Oval was keen to be a part of the whole thing for a number of reasons, not least because here was a car that could snub the Corvette but also because, generally speaking, Ford was about to unleash its performance-focused plan that would see them eventually sell tons of Pony Cars and dominate international endurance racing by the middle of the decade.

By the time it had arrived, it was parked in Shelby's new shop that was once home to Lance Reventlow's gorgeous Scarabs. Former Scarab fabricator Phil Remington kept calling the Venice shop home and began working for Carroll. It's his hands that will be all over the first Cobras built Stateside and just about everything else that rolled out of Shelby American Inc.

In April, the prototype was shown to a drooling crowd at the New York Auto Show. Despite the ultra-positive first impression, the Cobra was never a seller - not that Shelby could put together that many cars anyway. Still, enough were ordered for Shelby to send paperwork across the Ocean to France for the FIA to give its approval over the car's compliance with the rules. By that time, the Fairlane 4.2-liter V-8 had already been replaced by the now-famous 4.7-liter unit with its 'thin wall' block casting that kept the weight down. When introduced, the Cobra was about 1,000 pounds lighter than a Corvette and it handled better due to the shorter wheelbase, the all-round independent suspension and discs (Corvettes and Ferraris still came with rigid rear axles), and rack-and-pinion steering, not recirculating-ball type like in the 'Vette.

But the S/C and full-blown Competition-spec Cobra 427s were all fitted with the actual 7.0-liter engine that would also end up in Ford's Mk. II and Mk. IV Le Mans winners. It's unclear why Shelby even created the Cobra 427 - as it was never eligible to race in the GT ranks of an FIA-sanctioned event - but, for all it's worth, Chevy first shoehorned a 7.0-liter V-8 of its own in the second-generation Corvette in '63 and this probably rose some eyebrows over at Shelby American.

As you'd expect, a real Cobra 427 is rare as only the first 100 road-oriented examples made actually came with the 427 FE Series V-8, alongside the racing cars, and the last few copies built in late 1967. The car you see here is as close to a Cobra poster queen as possible: it's got the correct 427 widened bodywork, the competition white Halibrands with polished lips, the S/C visual kit complete with a roll hoop and bolted-on overriders, and the 1965-era Shelby American livery finished off by the A-Production class badges on the sides. It looks like a replica but it's not. It's the real deal.

The Cobra comes with one light cluster at the tip of each fender with the round indicator below. When outfitted for night-time racing, a Cobra would receive up to four more additional light clusters attached to the nose for better illumination of the road ahead. The riveted hood is one of the few elements that's shared between the Mk. III Cobra 427 and the Mk. III Cobra 289, although the size of the hood scoop may vary. By following the line of the hood you can easily see how bulbous the front fenders really are as they rise above the line of the hood (hood scoop notwithstanding).

When new, this car came with a full-size windshield with a chromed frame as well as wind deflectors on either side (no side windows for the roadster, you could only get them if you ticked the optional hardtop). However, those 'amenities' were deleted as this car was turned from a street-spec 427 to a semi/competition-spec one. As such, all that's left today is a tiny wind deflector (and it's not even good at doing that due to its extra-low heigh) placed in front of the driver. The curved piece of glass barely clears the top of the wooden-rimmed steering wheel. The Cobra also lacks a passenger's side exterior rear-view mirror. Instead, there's only one mirror on the driver's side and another, in the middle, on the bodywork that cradles the dash.

Aft of the front wheels there's a small vent with four angled louvers. The all-important '427 Cobra' badge is located directly above while the roundel with the racing number is nestled between the door, the side headers, and this vent. The doors too are different compared to those on early, narrow-body, Cobras as those were larger due to the smaller (almost non-existent) flares of the original Ace design. Mind you, the 427 is five inches wider than the 289 variant.

The bulbous rear fenders feature an added flare, just like in the front. The fuel lid is placed in a caved-in area of the right-rear fender. The Cobra you see here still shows the surviving soft-top pins but, of course, they can't be used because, A) the car has no windshield to secure the soft top to, and, B) the black roll-hoop is in the way.

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra exterior dimensions

|

Width |

68.00 inches |

|---|---|

|

Length |

156.00 inches |

|

Wheelbase |

90.00 inches |

|

Height |

48 inches (w/ hardtop) |

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra Interior

The interior of the Cobra is as no-nonsense as the rest of the car. The driver's served with a bucketload of gauges, necessary to know how the car's doing, and that's about it. There's a passenger's seat and some space behind these seats, as well as a diminutive glove box and some room in the pouches sewed to the interior door panels, but that's about it. A Cobra's cramped and not too comfortable and if you expect anything else from it, you're in the wrong, not the car.

As you climb in (more or less jump in, actually), you are greeted by that beautiful three-spoke wheel with a wooden rim and perforated metal spokes.

Talking about short, the lever of the gear shifter is actually quite short ending with a black, round knob. That's because it's placed atop the transmission tunnel that's higher than the top edge of the seat pillows. Unlike the shifter, the handbrake is placed within the passenger's footwell. The dash, covered in black vinyl, is held in place via two support arms that connect the dash to the transmission tunnel.

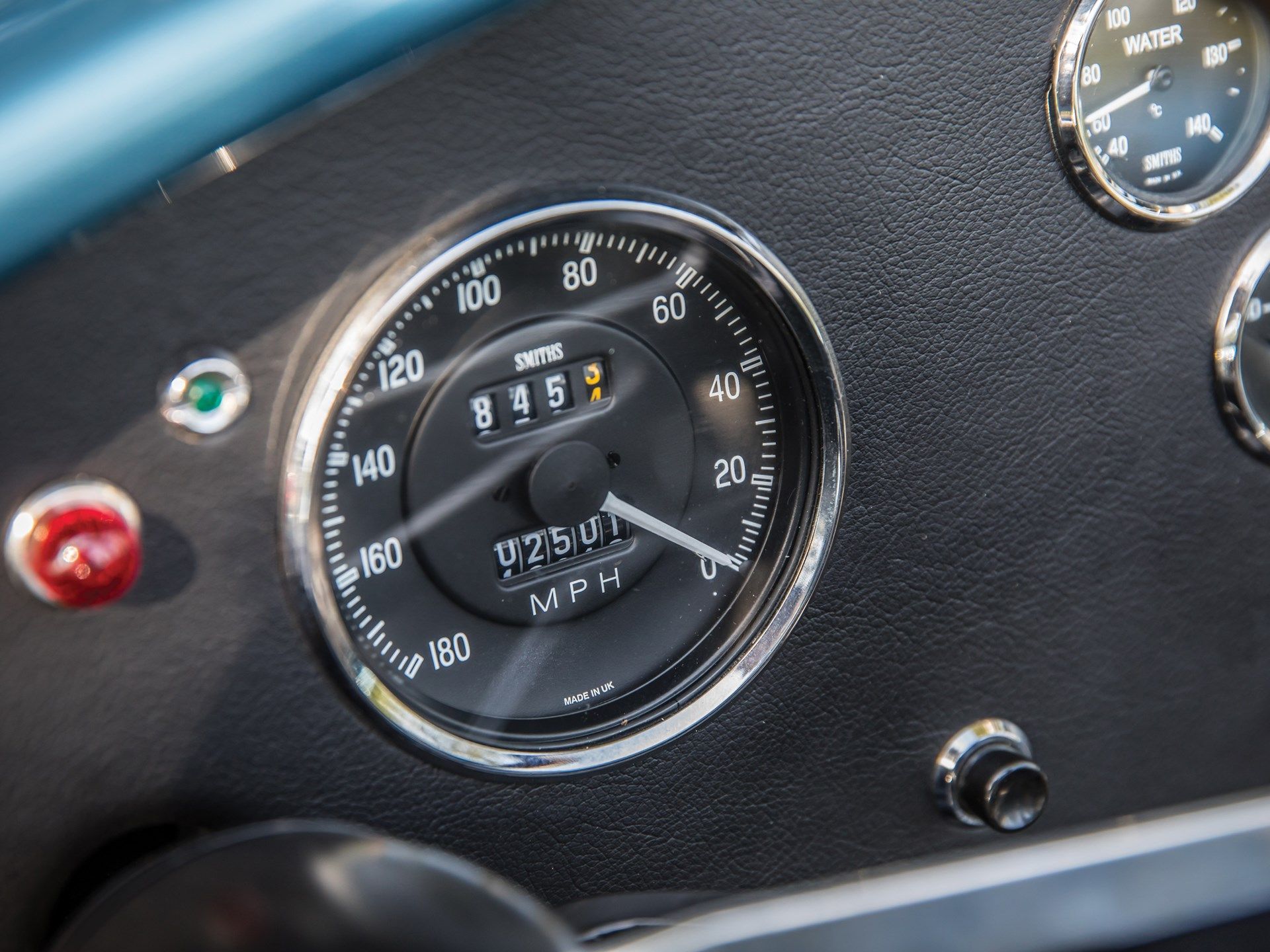

On the driver's side, you've got the tachometer (on the left) and the odometer (on the right) with three idiot lights in the middle - the rev light is the red one, of course. There are five more gauges in the middle of the dash organized on two rows (that's where you'll find your water pressure, temperature, oil pressure, and temperature) above a few knobs.

Driving a Cobra wasn't and, equally, isn't for the faint-hearted.

Then there's the fact that there are no features. You don't get a radio. You don't get a heater. You don't even get windows and nothing is adjustable. All you get, at the end of the day, is to drive it and, frankly, what more could you ask? If you want 'luxuries' of any kind get yourself a modern-day replica but we all know it won't feel the same, it won't break your back the same, it won't smell the same and, probably, it won't howl to the point of being unnerving either. We can't put into words quite how loud the 427 solid-lifter is but here's an account from Jenks who got a taste of riding shotgun in a FIA-spec Cobra 289, one of only five works cars built for the 1964 World Championship season that is.

"The juddering, noise and vibration when the engine is started has to be experienced to be believed," he wrote, adding that "there is no rising crescendo to peak rpm before the driver changes gear, there is just a shattering explosive noise and the engine is doing 7,000 rpm." The British journalist, who was well accustomed to being the passenger in some ludicrously fast cars (he famously co-drove to victory with Sir Stirling Moss in the 1955 Mille Miglia) said that "with his foot off the accelerator pedal there is comparative quiet, but he only has to prod it lightly and there is this shattering explosion of noise again and there you are at the next corner with little or no feeling of actual acceleration."

He also reflected on the car's handling, of which, he reckoned, wasn't much to speak of as you always have to add copious amounts of lock into and out of corners to keep yourself away from the weeds or whatever's residing next to the tarmac. "Because of the negligible cornering power the car possesses, a twisty road becomes a series of 'fits and starts' with the steering wheel kicking and juddering and the whole car alive with shaking and vibration."

Jenkinson's opinion is echoed by Bruce Ropner, who owned and drove an RHD example built by AC to FIA specs in 1964. "The Cobra was a hairy car to drive," Ropner said. "It was a rocketship in a straight line but you needed to be careful on the corners." Car & Driver, however, who road-tested a street-spec 427 in 1965, argues that a 427's got better road manners than the early 289s due to the chunkier tiers, coil-spring suspension, and beefed-up chassis rails. " handles properly, thanks to a completely new all-independent suspension system that is traceable to the deft hand of Klaus Arning, the Ford Motor Company genius responsible for the impeccable handling of the Ford GT," C/D writes before mentioning that "the old tubular AC chassis had considerably less torsional rigidity than the rail frame of a Model T," according to a Ford employee.

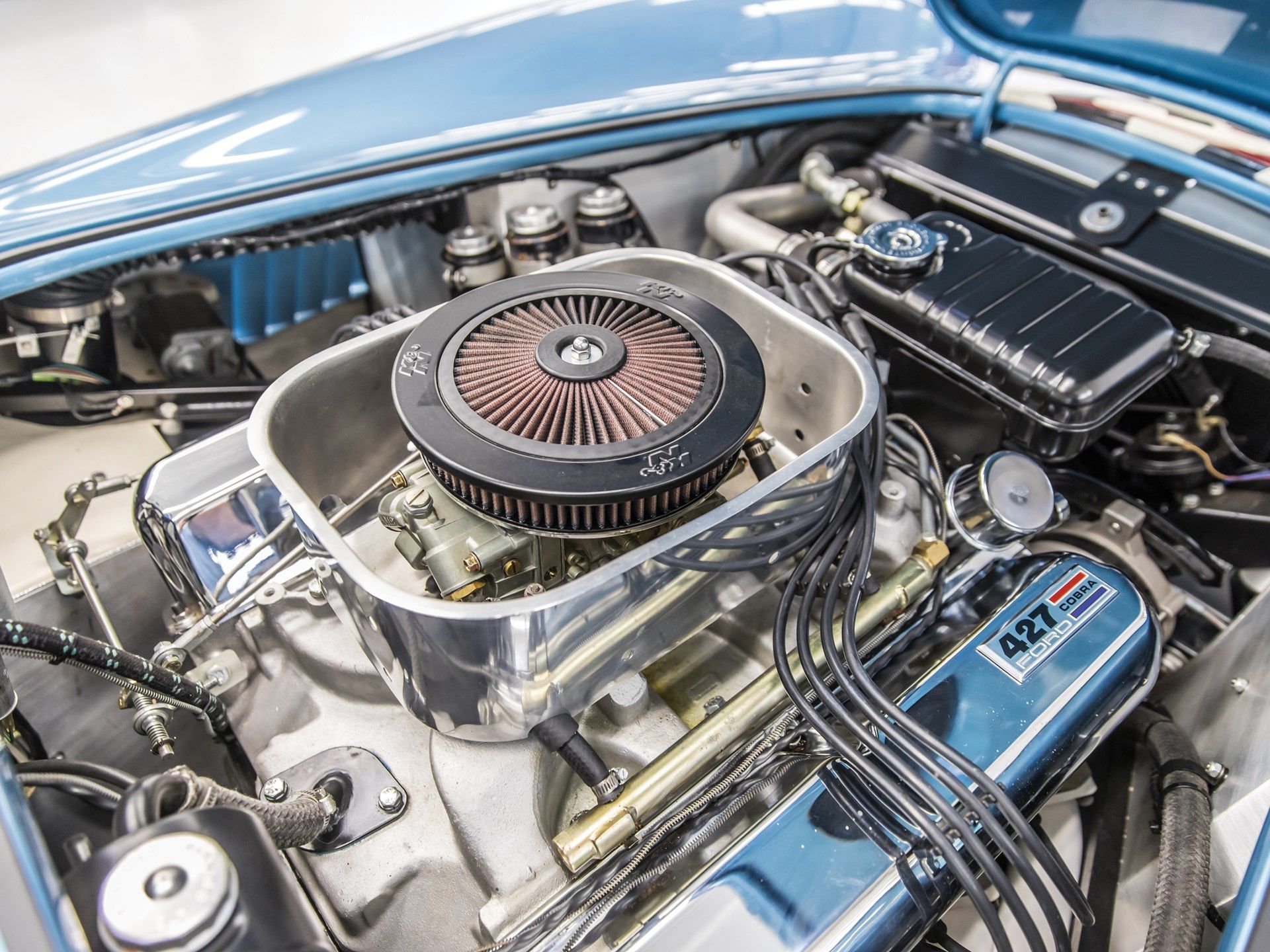

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra Drivetrain

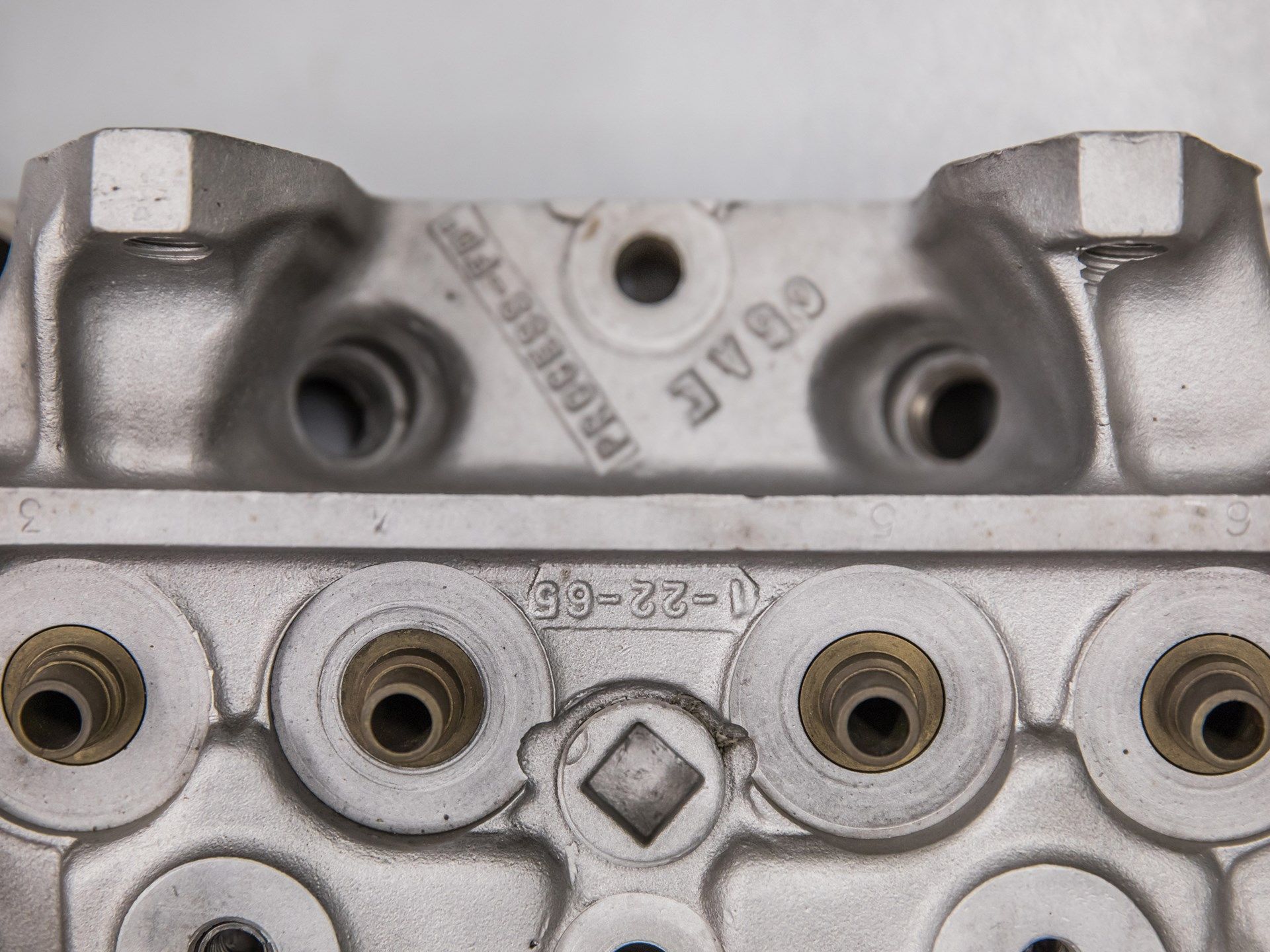

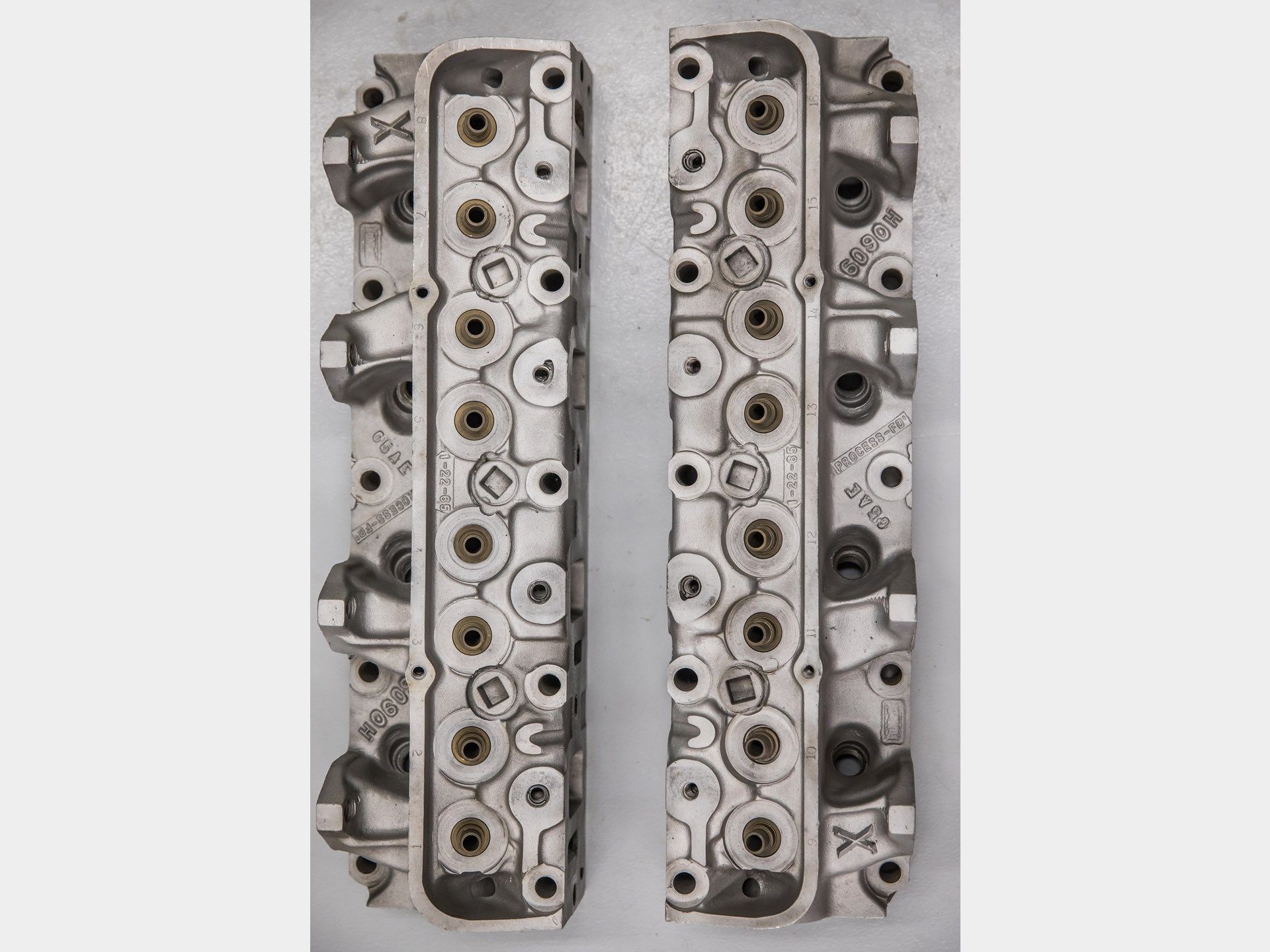

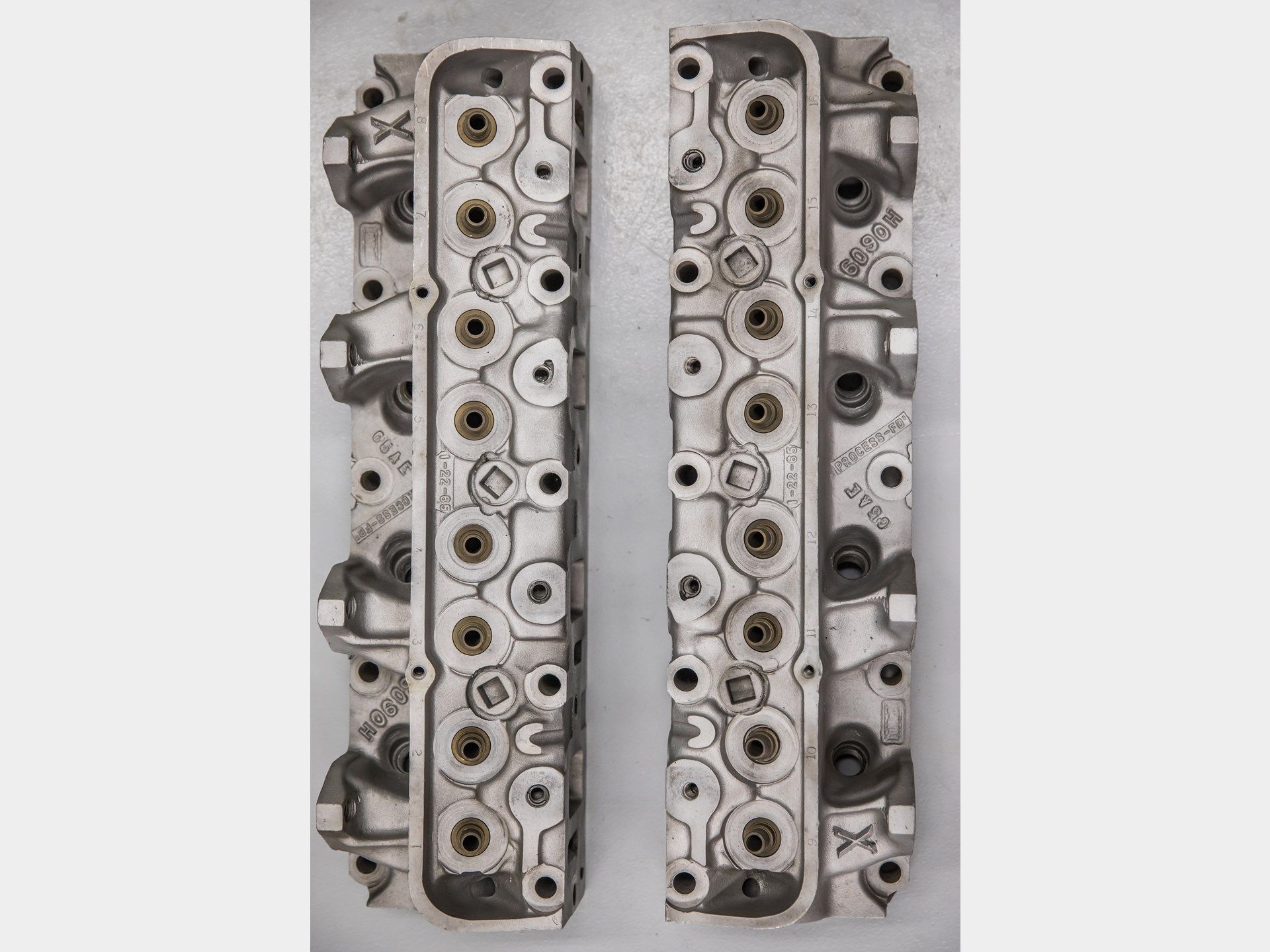

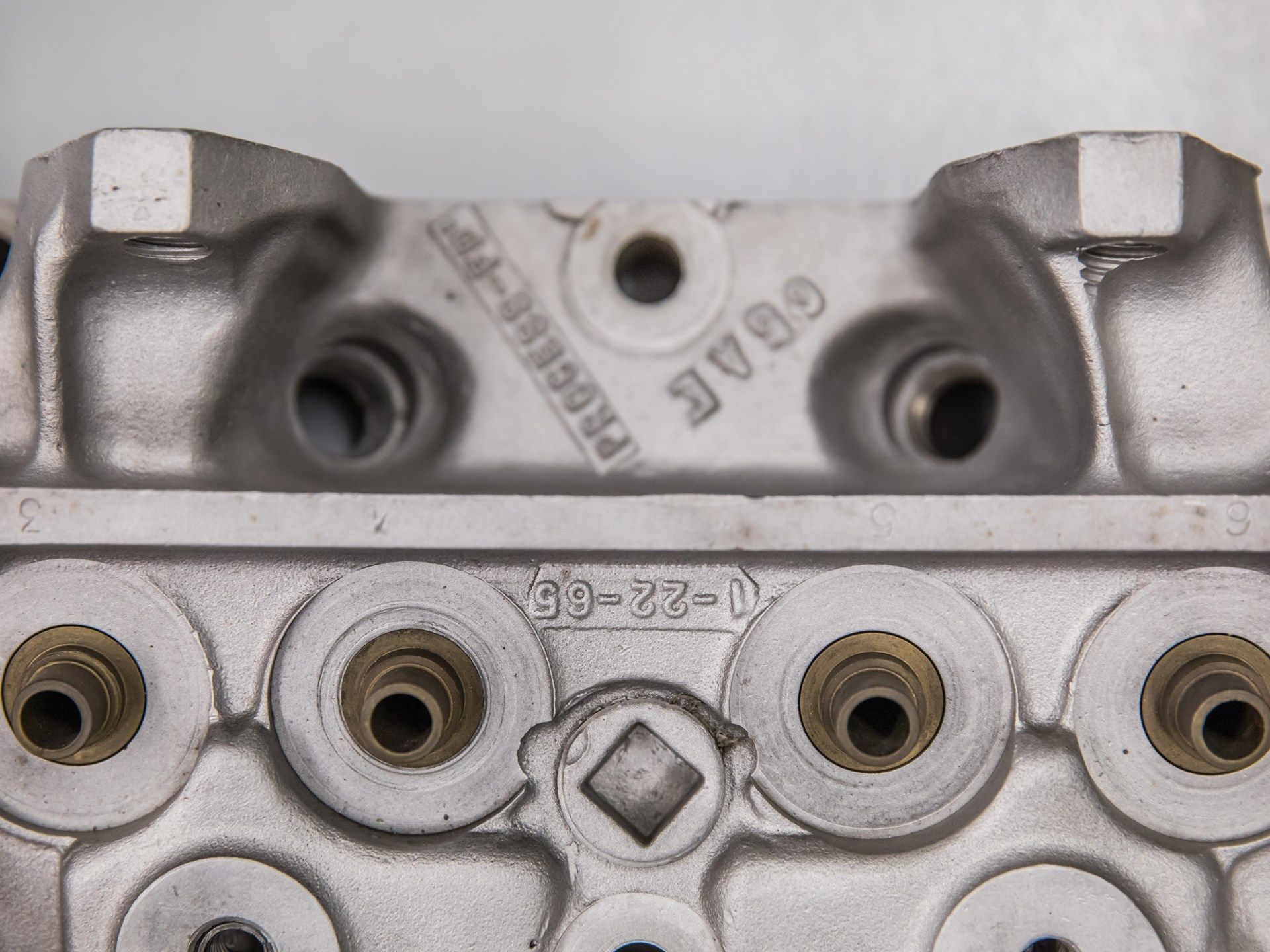

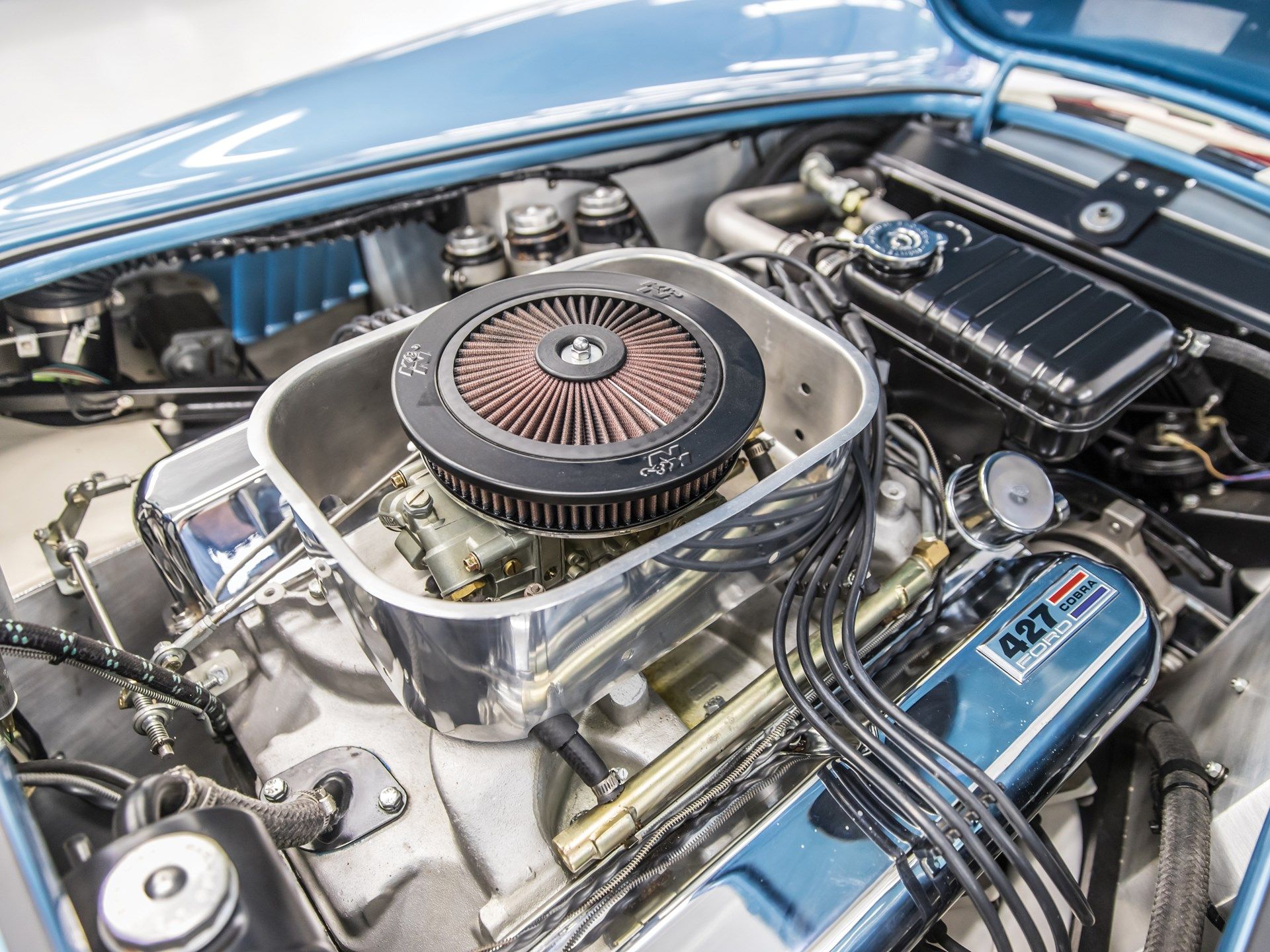

Introduced for the first time in 1963 for use in NASCAR competition and drag racing, the FE series solid-lifter V-8 with a displacement of 7.0-liters features cast iron heads and block. With a compression ratio of 11.0:1, identical to the 289's, the mighty 'side-oiler' puts out anywhere between 420 and 510 horsepower, depending on application. In a street-oriented 427, it usually didn't make more than 425 horsepower while Competition-spec cars enjoyed over 500 ponies. Max power is achieved at 6,000 rpm, 1,000 rpm before the redline. Max torque is about 480 pound-feet and, as with any American V-8, it comes in early. You've got all the torques at under 4,000 rpm to the chagrin of your rear tires.

But, in all seriousness, a Cobra 427 doesn't really need a four-carb setup. Already, when introduced, it became the fastest American road-going car, at least 100 horsepower clear of an Aston Martin DB5, 165 horsepower over what an E-Type 4.2 could muster and, more importantly, 125 horsepower more than a 250 GTO. The 'Vette, however, was a lot closer with its own 7.0-liter engine in place. In '66, with three two-barrel Rochester carbs, a Corvette C2 427 put out 430 horsepower and 460 pound-feet of torque. The following year, the Tri-Power V-8 topped out at 435 horsepower. But the Corvette was always heavier.

You see, despite all the strengthening done by Shelby American to keep all that torque and power from essentially tearing the Cobra into pieces (including thicker frame rails, thicker tubes placed farther apart and extra bars for rigidity), the Cobra remained light. The body was still made from aluminum and the change of suspension and steering didn't add too many pounds at all. A 427 weighed anywhere between 2,250 and 2,480 pounds depending on specification while a Corvette C2 tipped the scales at over 3,200 pounds any day of the week. Sure, Chevy offered a grand tourer, not a bare-boned roadster but we're talking weight saving here.

The gearbox is a four-speed manual with short throws that, with a 4.11:1 final-drive ratio, only allows the Cobra to reach 134 mph before hitting the engine's 7,000 rpm redline. With the common 3.54 final-drive ratio a top speed of 155 mph is possible, about 25 mph more than what a Cobra 289 could muster. The Corvette 427, however, could do 140 mph in top gear with the 4.11:1 final-drive ratio.

But no 'Vette can keep up with a big-engined Cobra on the drag strip. The car's acceleration is vicious, helping the Cobra to remain the fastest accelerating American car throughout the '70s and '80s as tight emission regulations stopped performance cars dead in their tracks. Still, a 0-60 mph sprint in 4.1 seconds is respectable to this day considering a 13-year-old Ferrari F430 needs four seconds (4.0) flat complete this task while aided by that clever semi-automatic transmission. A '66-'67 Corvette with the Tri-Power Big-Block under the hood was also tremendously fast for its day but still about 0.7 seconds slower.

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra drivetrain specifications

|

Engine |

7.0-liter OHV, FE Series, solid-lifter, naturally aspirated V-8 |

|---|---|

|

Output |

About 450/510 horsepower at 6,000 rpm |

|

Torque |

480 pound-feet of torque at 3,700 rpm |

|

Compression ratio |

11.0:1 |

|

Bore x stroke |

4.24 × 3.78 inches |

|

Fuel feed |

One four-barrel Holley carburetor |

|

Steering |

Rack-and-pinion unassisted |

|

Gearbox |

Four-speed manual |

|

Suspension |

Independent all around with double wishbones and coil springs |

|

Brakes |

Discs all around |

|

0-60 mph |

4.1 seconds |

|

0-100 mph |

10.3 seconds |

|

Top speed |

155 mph (with longer gearing) |

|

0-100-0 mph |

14.5 seconds (on road tires) |

|

Weight |

Between 2,250 and 2,480 pounds depending on specs |

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra Prices

Any original Cobra is expensive as not too many were made. Despite its huge success on track and popularity (over 60,000 replicas have been built since the original was introduced for the public in '63), Shelby American only assembled 998 units until 1968 of which most were leaf-sprung 260/289 Roadsters and only 348 were 427s with coil-spring suspension. Of those 348 units, not all survived with a fair few being lost in crashes (not unexpectedly).

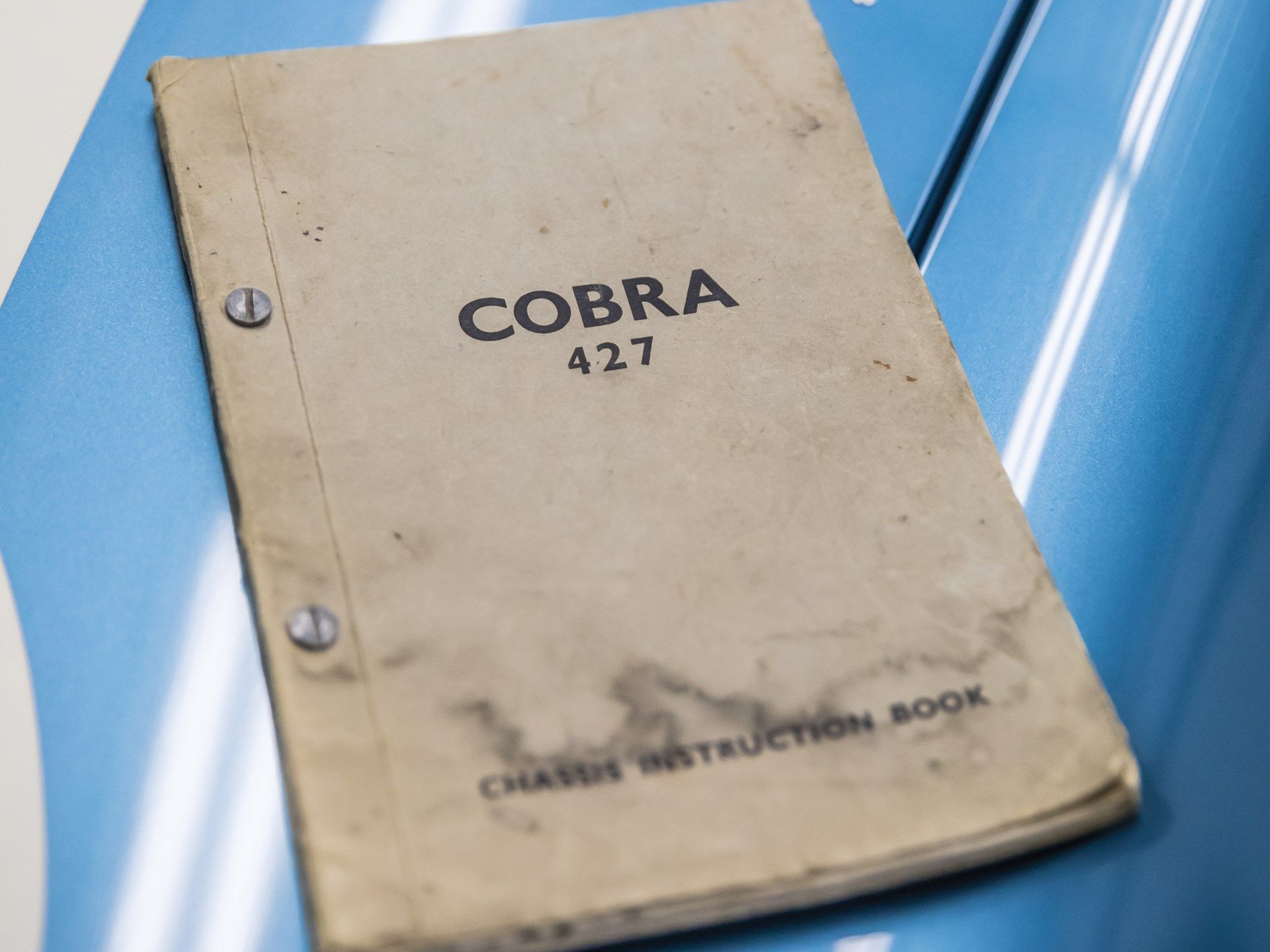

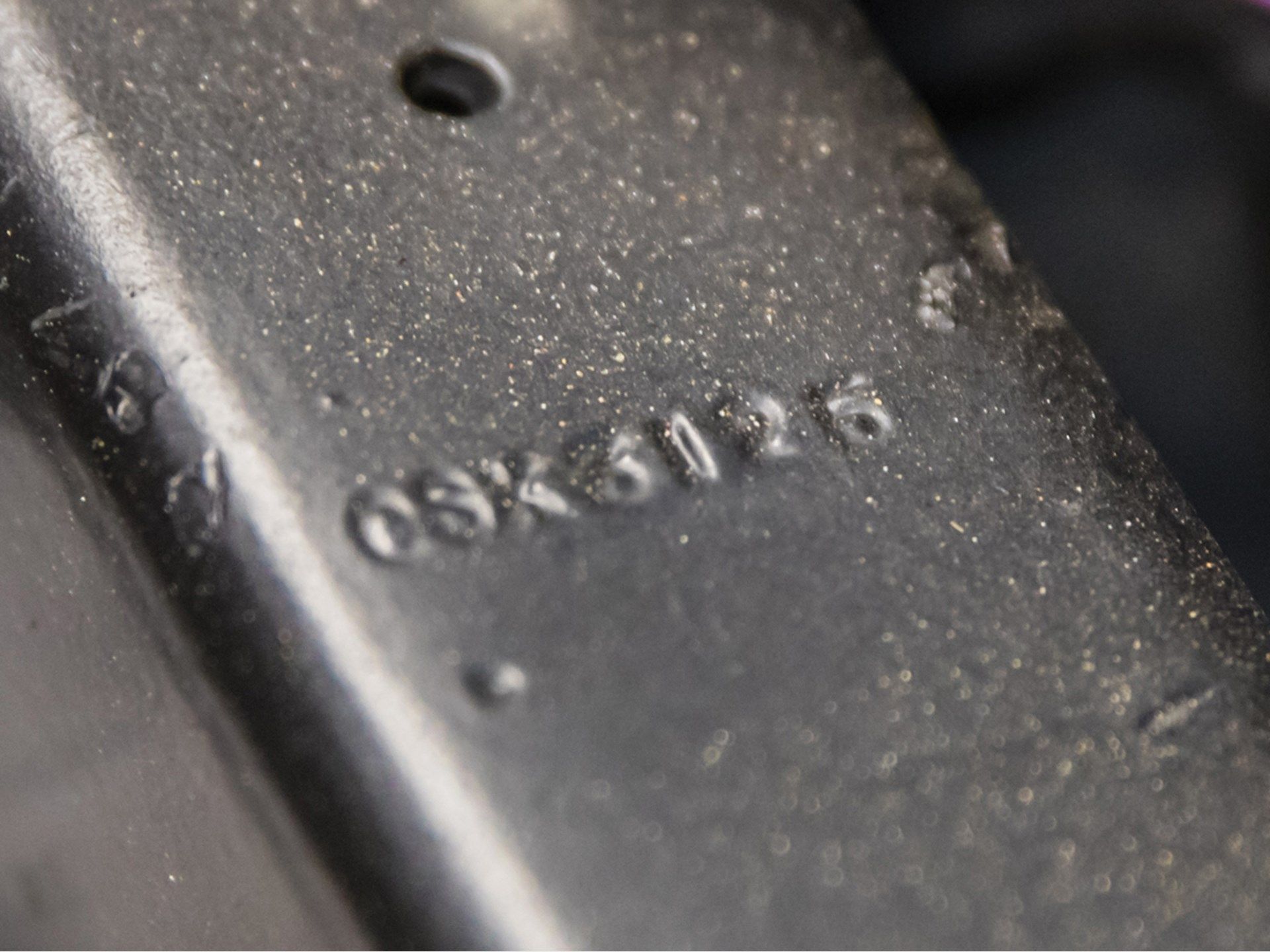

As such, what has survived the test of time has become the object of adoration and is only accessible if your pockets are almost bottomless. Gooding & Co. sold a 'barn-find' 1967 Cobra 427 with only 18,000 miles on the clock for little over $1 million back in 2018 and other cleaner examples have traded hands for anywhere between $1.3 to $1.5 million. This particular example, chassis #CSX3125, was tipped to fetch anywhere between $1.25 and $1.5 million at Monterey earlier this year.

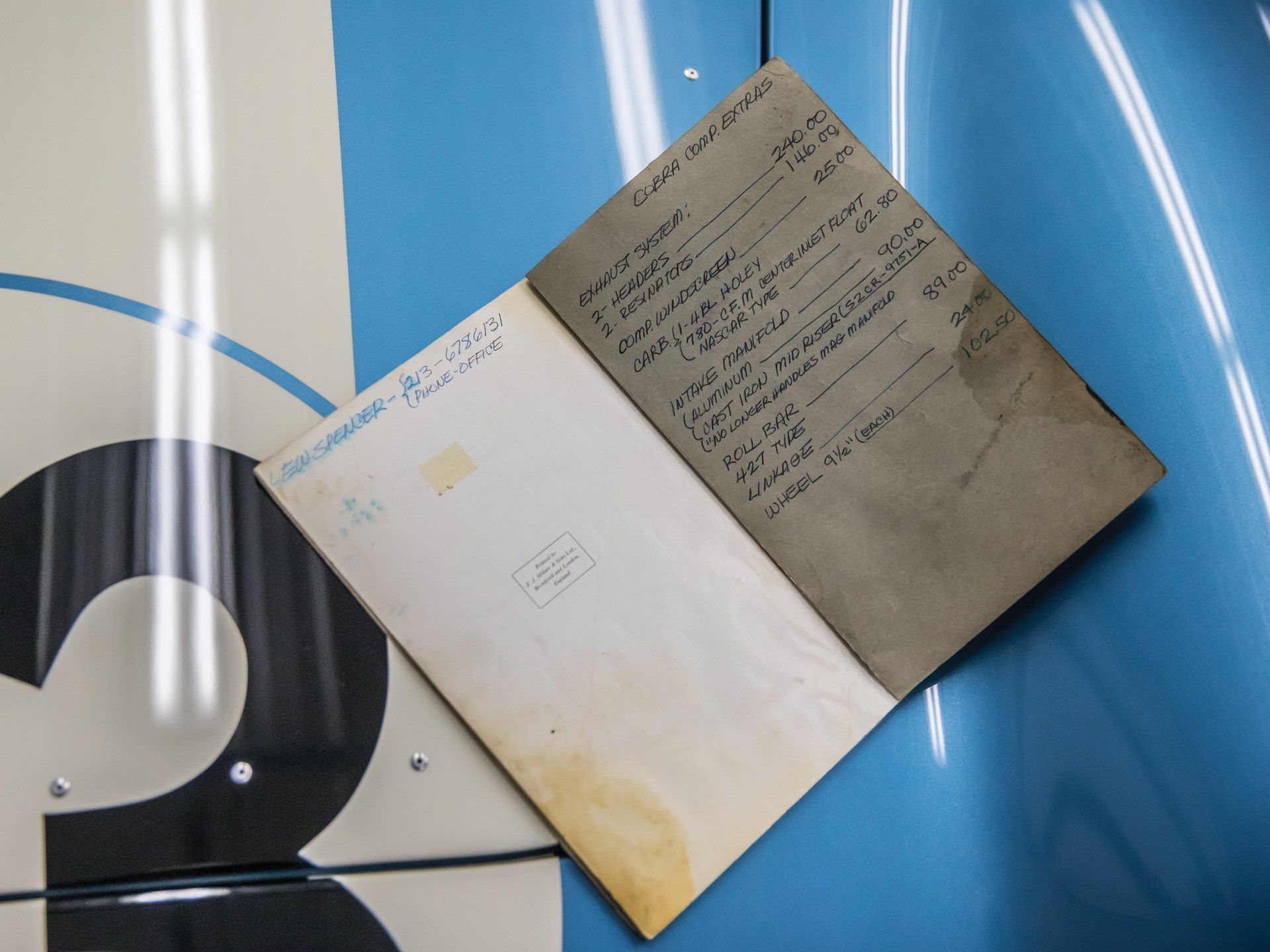

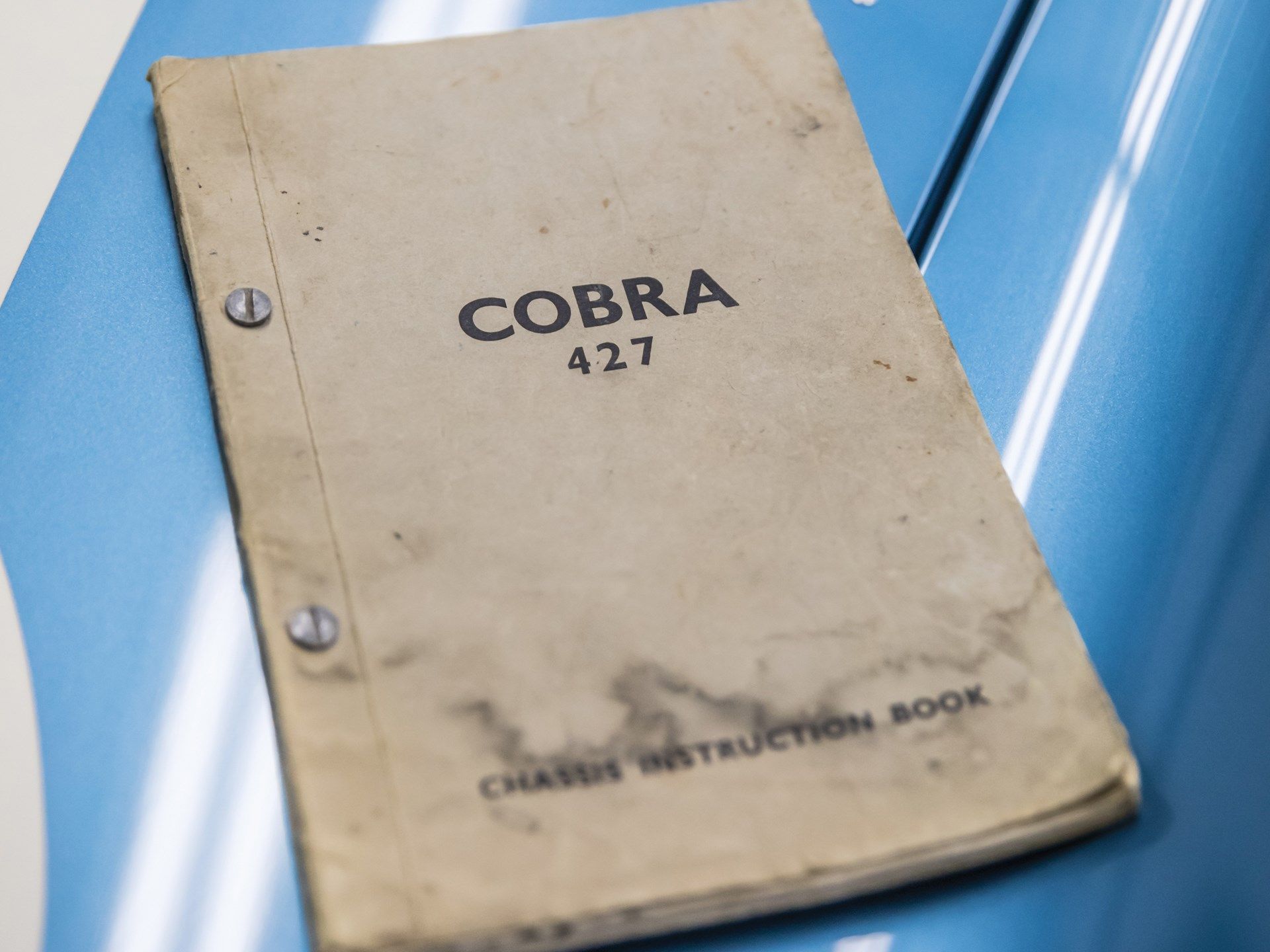

The car you see is the 25th street-spec Cobra 427 ever made (part of the first series of street examples) and it left Shelby's shop painted in white. In September of 1965, it was sold to its first owner in Texas who duly converted it to SCCA A-Production specification, maybe due to the fact that he couldn't get his hands on one of the few Competition models. He acquired all the parts for the conversion directly from Shelby and then raced the car for a while before selling it to infamous racer/escapee John Paul Sr. It was driven to a number of wins in 1969 by Paul before he too sold it on. Finally, in 1972, its period racing career ended and, by the time it was sold in London, England, a conversion to street spec was commissioned. Since then, however, the car has returned to S/C spec.

1965 Shelby 427 Cobra Competition

1965 Chevrolet Corvette 427

The futuristic second-generation Corvette, known as the Sting Ray (then the two words were brought together), brought the Bowtie's sports car to new heights of performance that seemed, previously, impossible. Remember, after all, that the C1 debuted in 1953 sans a V-8. Fast-forward to 1966 and a 7.0-liter big-block V-8 became available and it was quite the monster, shaming most European sports cars at the time.

The 427 first arrived with as much power as the high-compression 396 (6.5-liter) V-8 but it offered 45 more torques (460 pound-feet versus just 415 pound-feet). Having said that, power outputs were sometimes understated/overstated by manufacturers and, in hindsight, the 396 probably lacked 20 ponies compared to the 427. In 1967, the L88 became available and this was the engine to go for if you wanted to go racing with your Corvette. It featured lightweight heads, bigger ports, an even hotter camshaft, insane 12.5:1 compression, an aluminum radiator, and a small-diameter flywheel, as well as a four-barrel Holley carb like in the Cobra. While, officially, it made no more than 435 horsepower, many say the real gross rating was closer to 560 horsepower at 6,400 rpm - but it required 103-octane fuel. An L88 Corvette cost you at the time an extra $1,5000 over the $4,240 MSRP of a Corvette for a total of $5,740. Not much when you consider that, four years earlier, a Cobra 289 Roadster advertised for $5,995.

Read our full review on the 1965 Chevrolet Corvette 427

1963 Ferrari 330 GTO

For 1962, the FIA decided to switch its focus from purpose-built prototypes and, instead, allow the World Endurance Championship to be won by GT cars. Ferrari answered the call for GTs by creating the legendary 250 GTO and, while the GTO has become one of the most successful race cars of its decade and is, nowadays, the most expensive automobile ever to be sold at auction, Ferrari also built a GTO with a bit more oomph at the time.

Known as the 330 GTO, this big-engine GT was actually entered as a sports prototype due to the fact that only three copies were ever made. Making the best out of a rule that allowed manufacturers to enter prototypes powered by engines with a displacement of up to 4.0-liters, Ferrari took the engine off the 400 SuperAmerica and made it fit within the chassis rails of the 250 GTO.

The job in itself wasn't a daunting one and, in fact, the proportions of a 330 GTO almost echo those of a 250 GTO, although the 330 GTO is slightly longer. But the surprise is under the hood: instead of the Tipo 168/62C 3.0-liter Colombo V-12, the 4.0-liter V-12 with its longer stroke was nestled under the hood that now needed a bigger scoop to clear the taller unit (compared to the 250 GTO). Chassis #3673LM debuted in the Nurburgring 1,000-kilometer race in 1962 where Willy Mairesse and Mike Parkes finished second overall winning the Prototype 4.0-liter category behind a Sports 3.0-liter-entered Dino 246 SP.

Then, in 1963, Ferrari further modified the chassis of the 330 GTO extending the wheelbase to 98.4 inches, the base actually being the 250 GT Lusso's underpinnings. The new rear end, part of a special bodywork devised by Pininfarina, also mirrored the Lusso's design with special plates put in place to clear the tall rear wheels. The changes were deemed successful when Pierre Noblet's 330 LMB was able to exceed 186 mph during the test day before the 24 Hours of Le Mans. All of the three LMBs were entered in the 1963 edition of the twice-around-the-clock race with one car for N.A.R.T., one for Colonel Ronnie Hoare's Maranello Concessionaires, and the latter for Noblet. They were all fast qualifying in seventh, ninth, and 11th overall respectively but only the Jack Sears/Mike Salmon British entry finished in fifth overall although that was enough to win in the Prototype +3.0-liter class.

Thereafter, the 400 horsepower coupes didn't race for much longer. Lorenzo Bandini won his class with one in the Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch but he only finished eighth overall and, later, Dan Gurney scored third outright in the Bridgehampton 500 Miles race. Come the end of '63, Ferrari moved on and focused solely on racing mid-engined cars and the 250 GTO/64 in the Grand Touring ranks leaving the 330 LMB to rest for forever in the shade of the less muscular 250 GTO.

While it's hard to compare this with the Cobra 427 as the 330 GTO/LMB was conceived for racing purposes alone - albeit with street use possible due to the way the rules were laid out at the time -, we think it's the only GT-esque big-engine Ferrari that could stay close to the Cobra 427 although it won't match it in terms of acceleration/braking but will surpass it given a track composed of massively long straights such as the Circuit de la Sarthe in Le Mans or Reims. Also, as expected, if a 330 LMB is to appear for sale publicly, it will most likely trade hands for more money than even the $5.1 million Super Snake because that's what the allure of the Prancing Horse can do.

Conclusion

Carroll Shelby's Cobras put his company on the map and, on top of that, put America on the map in international GT racing. The lightweight and massively fast roadsters outpaced anything from Jaguars to Porsches and from Ferraris to Aston Martins with apparent ease. They won just about anywhere - but for Le Mans, due to the lack of top speed - and, in street trim, were the fastest cars money could buy for many years.

As such, the Cobra 427 can only be seen as an improvement to an already potent breed. It delivers on the promise of more power, as if that was really needed, but it does a lot more than just that with the beefed-up and recalibrated chassis, better suspension components that allow for better balance mid-corner, and, also, a quicker steering rack. With such performance claims as a 0-60 mph sprint of 4.1 seconds 54 years ago, it's not easy to see why the Cobra 427 became the dream machine of many and the golden standard for many, many American open-top sports cars that came after it.

Its rarity only adds to the legend and so do the myriad of replicas that help to boost the prices of authentic, period-made (Shelby American itself also built a number of 'continuation' cars throughout the years) examples. That's why you'll pay vintage Ferrari money for one but what we can guarantee is that no vintage Ferrari will offer you the kind of thrills and spills a big-block Cobra's got in store for the driver that's prepared to push the envelope!