Buried deep into the Brazilian jungle sit the remains of what was once Henry Ford’s utopian city. A place where one of the richest and most influential men on the planet wanted not to make money, but to - quote - help develop that wonderful and fertile land.

And I can tell you right now that Henry Ford definitely didn’t make any money out of his dream city. In fact, it turned out to be one of his biggest failures - but we’ll get to that later. So keep reading to find out the story of Fordlandia, an American attempt at making an American rubber factory and an American-style community in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon.

Ford Created A City To Cut Costs

It’s the early 1920’s and Britain’s stronghold on global rubber is still alive and well, after holding a monopoly for decades with its plantations in the Far East and fixing prices at a high level.

But even so, Henry Ford’s automotive business is booming, and he needs a lot of rubber for his cars, and as cheap as possible, for making tires, gaskets and valves.

In fact, it’s estimated that three quarters of all the rubber imported into the United States at this point was used in the automobile industry, so Henry Ford set out to find a way to cut costs and provide a steady supply of natural rubber for his business.

And apparently the answer to all of this was simple: build an American rubber plantation on a one-million hectares piece of land in the Brazilian rainforest that would be called Fordlandia.

Henry Ford Never Even Stepped Ford On Fordlandia

So in 1927, with high spirits and overwhelming positive news coming from the Brazilian press, Henry Ford announced that he would embark on a tour of South America that included the site of the plantation. But this would end up to be the first misstep, because the tour never happened. In fact, Ford never set foot on the utopian city he envisioned.

Ford Didn’t Do Its Homework

At this point, you should know that Brazil used to be the number one source of natural rubber for the whole world, but its spot as the leader was taken by the British, who started producing its own rubber in the Far East, where pests and plant diseases that were the usual suspects for rubber tree deaths were non-existent. So their plantations thrived, whereas Brazil was left behind.

Another thing you should know is that Henry Ford, as witty as he was, had no clue about how to grow rubber trees and no idea about how the local population was living. And he really had no trust in experts and advisers that tried to warn him about the potential failure Fordlandia could become.

The Worst Scenarios Possible, Almost On Purpose

So the plan went ahead, and in August of 1928, two ships filled with everything from door knobs to clothes set sail for the Amazon to establish a settlement. Work began to clear the jungle in order to make room for the buildings that would be erected, but progress was slow, partly because the settlement’s first manager, the Danish sea captain Einard Oxholm, had no agricultural experience.

The fact that the site of Fordlandia was on top of a rise didn’t help with the construction effort either, because it was too far inland for cargo vessels to haul materials on the rocky Tapajo river before the rainy season. Because of this, food supplies were dwindling fast, and the crew assembled at the future site of the city revolted in late 1928. It would be just the start of local uprisings at Fordlandia.

By 1929 Fordlandia Started to Grow

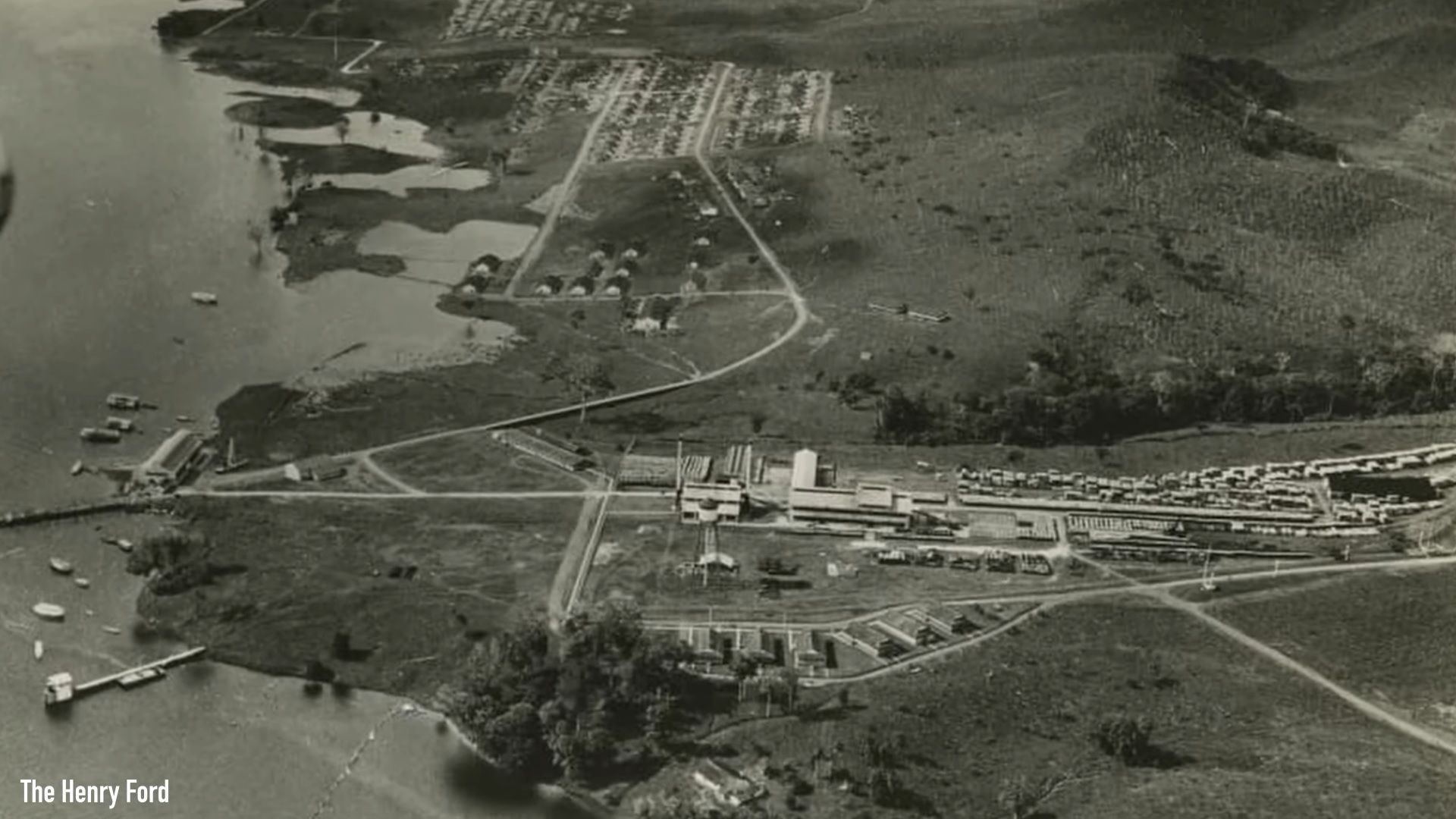

Materials finally began to arrive in early 1929, and the basic street grid was laid out, as well as a separate neighborhood for the American staff that worked there, called the Vila Americana. It had the best view of the city and was the only section with running water, whereas the Brazilian workers - who, to be fair, were given free housing - had to make due with water from wells.

By the end of 1930, Fordlandia featured modern hospitals with over 100 beds, schools, generators, a sawmill and its landmark structure, the water tower, which is still in place today.All seemed well and good until this point, two years after work began, but there were underlying problems that everyone seemed to miss at the time.

The Brazilian Military Had to Step In To Stop Violence

Although Ford was paying local employees a wage of 35 cents per day, much more than the typical 20 cents per day in the Far East, and offering free food, housing and medical care, it was far short of the 5 dollars per day earned by Ford employees in America. Moreover, the houses they built were sitting on the ground, as opposed to the local way of building places above the ground to avoid creatures crawling inside, and there was a strict meatless diet enforced, as well as a prohibition on alcohol.

All of these, plus the promotion of square dancing, poetry reading and a 9 to five work schedule, led to a violent uprising at the workers cafe, which quickly escalated and resulted in the vandalising of the city, with generators and manufacturing equipment being destroyed. The American managerial staff managed to escape by ship and violence finally stopped when the Brazilian military was flown in by Pan Am.

Locals Tried to Make the Best of a Bad Situation to Some Success

Now, a little explainer is in order, at least when it comes to that 9-5 work schedule that contributed to the violence. In the US, a lot of people are accustomed to this type of schedule, but in the Amazon, people like to work before sunrise and after sunset, because the heat and humidity during the day is really hard on the human body, and not many people can resist the conditions.

The alcohol ban also played an important role in triggering the 1930 violence, but eventually local workers circumvented the ban by setting up their own “Island of innocence” 5 miles upstream from Fordlandia, with bars, nightclubs and brothels.

After Fordlandia Failed, Henry Ford Tried Again, In Almost The Same Place

But let’s back to the rubber. Or, at least, what should have been rubber. You see, up until this point, the total production amounted to zero. Deforestation was slow and painful, the land was hilly, rocky, and infertile, and none of Ford’s managers had knowledge of tropical agriculture. This led to the plantation of trees from seeds of questionable quality, in plantations, close together, with the hope of getting a high yield.

But in their natural environment, rubber trees grow apart from each other as a protection mechanism against diseases and pests. So in 1933, after multiple failures in Fordlandia, Henry Ford tried his luck once more down river, acquiring new land and setting up a new settlement called Belterra.

This time around, he consulted Dr. James Weir, a plant pathologist, who managed to get his hands on 2,046 buddings from high-producing trees in the Far East and brought them back to Brazil to start growing at Belterra. And while Fordlandia wasn’t completely abandoned, it was clear that Belterra was a better place to produce rubber, so the major operations were transferred here, and by 1940, 2,500 employees were working at Belterra, while 500 were still at Fordlandia.

It Took Until 1942 For Ford To Produce Any Rubber

In 1942, 14 years after this whole adventure began, the first commercial tapping of rubber trees finally began, and 750 tons of latex were produced. It seems like a lot, but it was well short of the 38,000 tons Ford needed every year for his car business. And even though Belterra was producing rubber, it was still plagued by leaf fungus problems, and production was slow, although it had a good chance of becoming profitable, seeing how World War II cut off the supply of rubber from the Far East.

Failure Comes At Very High Cost

But in the end, it was a complete failure. After the war ended, Henry Ford was in poor health, and management of the company fell to his grandson, Henry Ford the second, who set out to cut costs as much as possible, and the first on the chopping block was Fordlandia. Ford sold it back to Brazil in 1945 for a mere 250,000 dollars, a fraction of the $20 Million invested over time in the Amazon. That’s over 200,000 million dollars in today’s money.

Ford’s dream cities had, at their peak, a total of 7,000 inhabitants, more than 2,000 workers, over 800 houses, schools, hospitals, a golf course, a power plant, a water purification plant, a pool, and, ultimately, over 3,5 million rubber trees. But it was all for nothing. Stubbornness and sheer distrust in agriculture experts turned a once glimmering hope into nothing more than a ghost town.

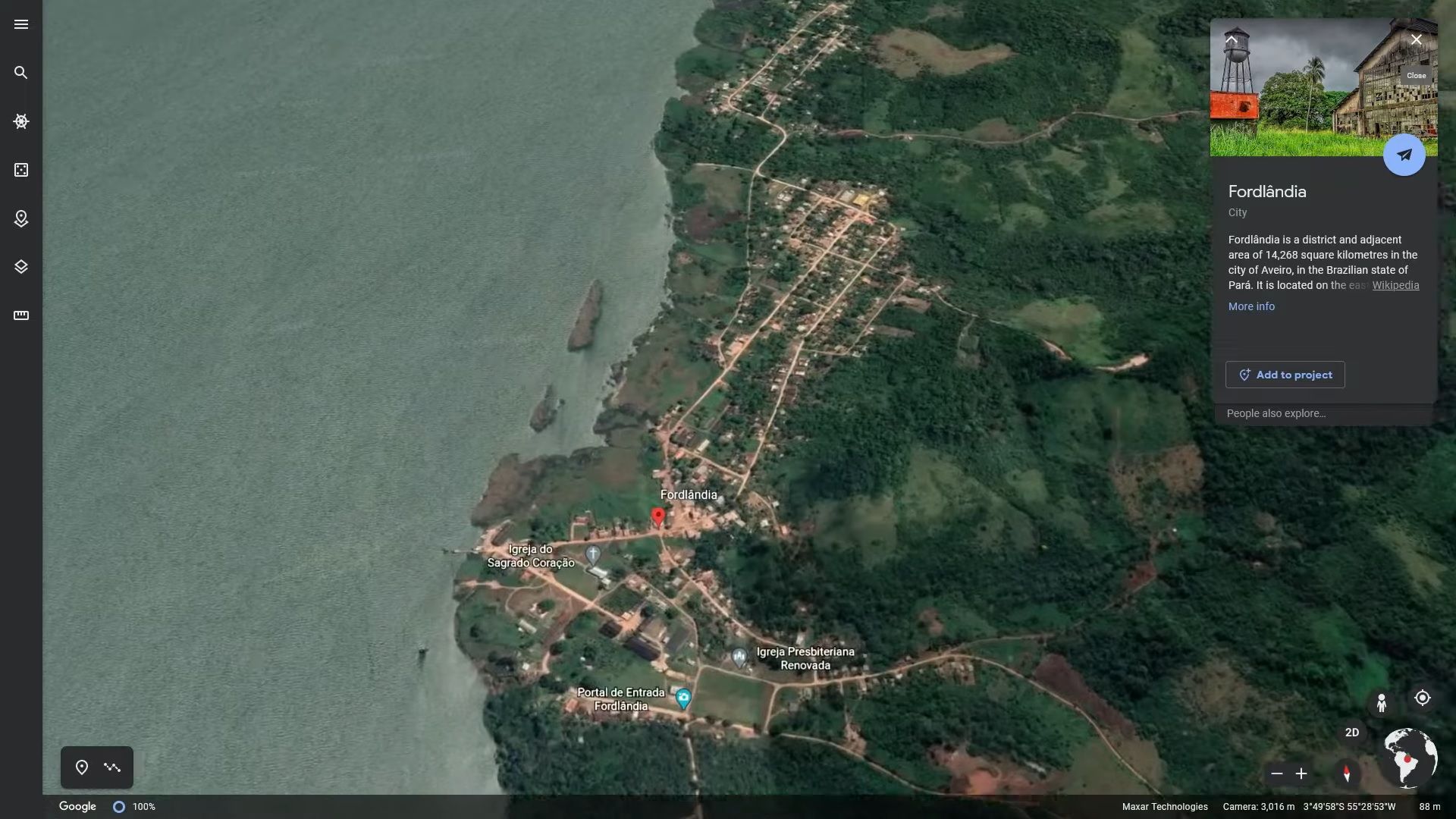

Until the early 2000s, less than 100 people were still living in Fordlandia, but as of 2017, nearly 2,000 people are living in what is now a district of Aveiro, in old, American-built houses, surrounded by century-old street lamps and fire hydrants. It’s a fascinating story, but I want to know what you think about it. So leave a comment below and I’ll try to answer as often as I can.