With no less than 54 driven wheels, a length of 570 feet, and a total output of almost 5,000 horsepower, these are just some of the highlights that make up the massively impressive Overland Train Mark II, the longest off-road vehicle ever made. Keep reading to find out the story behind this huge US Military machine, including its Cold War, nuclear-showdown roots, and its equally-impressive predecessors.

How the U.S. Army Land Train Came to Be

In the early 1950s, the United States and Russia weren't exactly buddies. A nuclear apocalypse was brewing, and the Americans needed a first line of warning to know if Russia was sending nuclear bombers over the Arctic Circle.

But after all of this was said and done, one question remained: what vehicles would the US Army use to build the line? It was, after all, one of the most remote regions of the world, with freezing cold temperatures and vast snow fields. Well, here is where the huge land train comes into play. But first, a bit of history, because there were a few predecessors to the massive 54-wheeled vehicle I mentioned at the beginning that can’t be ignored.

VC-12 Tournatrain – The Roots

Ok, so one year before the plan for the DEW Line was put in place, Robert Gilmore LeTourneau, a brilliant engineer and heavy machinery inventor, came up with a contraption called the VC-12 Tournatrain. It was basically a trackless land train, made to simplify and assist logging operations. With a 500 horsepower Cummins diesel engine connected to a generator, it worked more or less like a train locomotive, pulling three cargo trailers on immense, rugged tires.

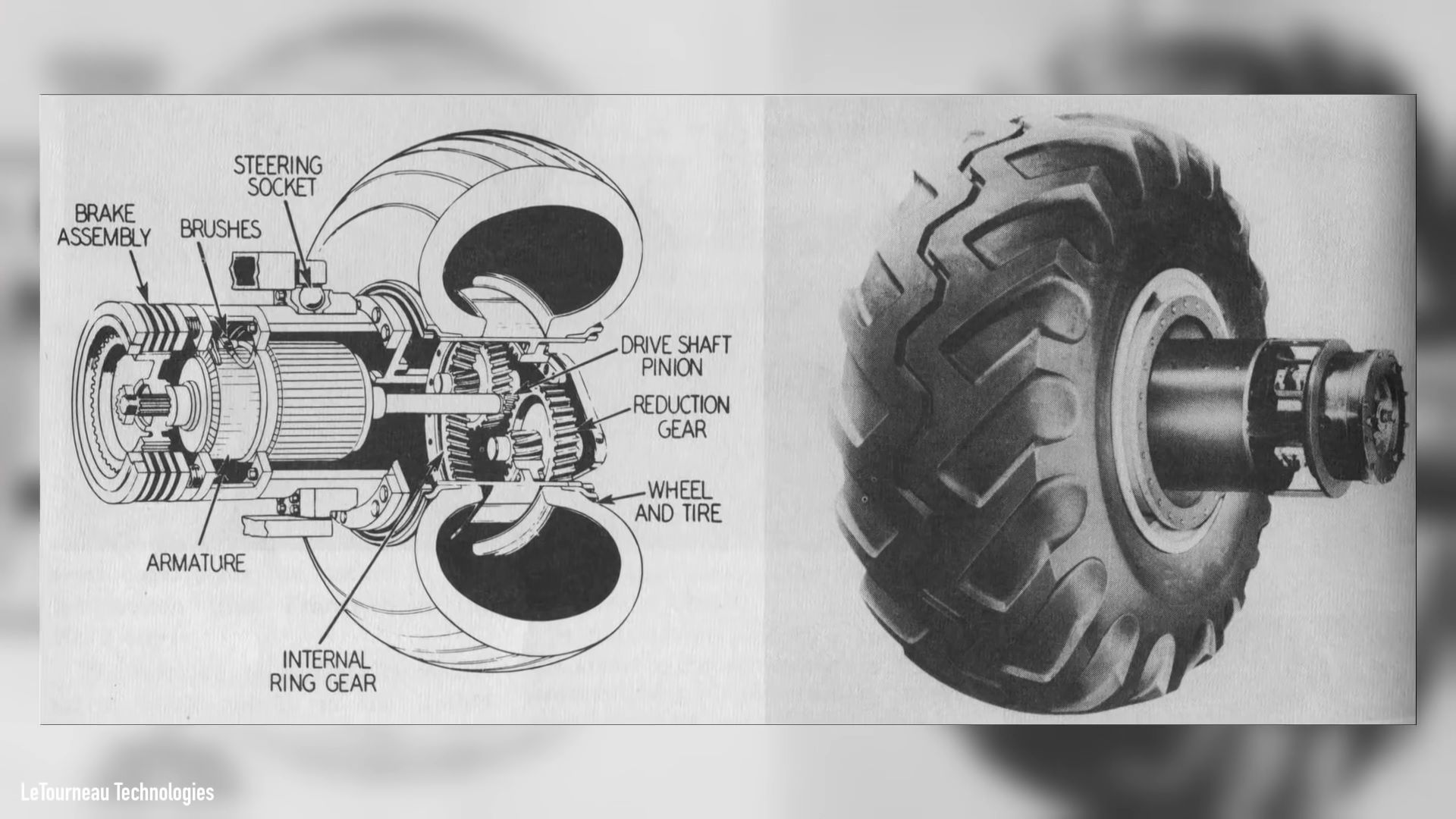

But the most important aspect of the whole assembly was the lack of a mechanical drive connection to the trailer wheels, which meant electric motors could be used to power every single wheel.

LeTourneau built a second version of the VC-12 that had three extra cargo trailers and an additional control cab at the rear with a second Cummins diesel providing power to the assembly. That’s 1,000 horsepower and 32 driven wheels, in case you’re keeping tabs.

As you can imagine, such an impressive creation caught the attention of some important people. Among them were representatives of Tradcom, the US Army’s Transportation Research and Development Command, who, incidentally, were directly involved in building the DEW Line, along with The Western Electric Company. Tradcom thought this would be the perfect vehicle to help build the Distant Early Warning Line, so it convinced the US government to pay for a prototype control cabin built by LeTourneau specifically for Arctic conditions.

Enter The Sno-Buggy

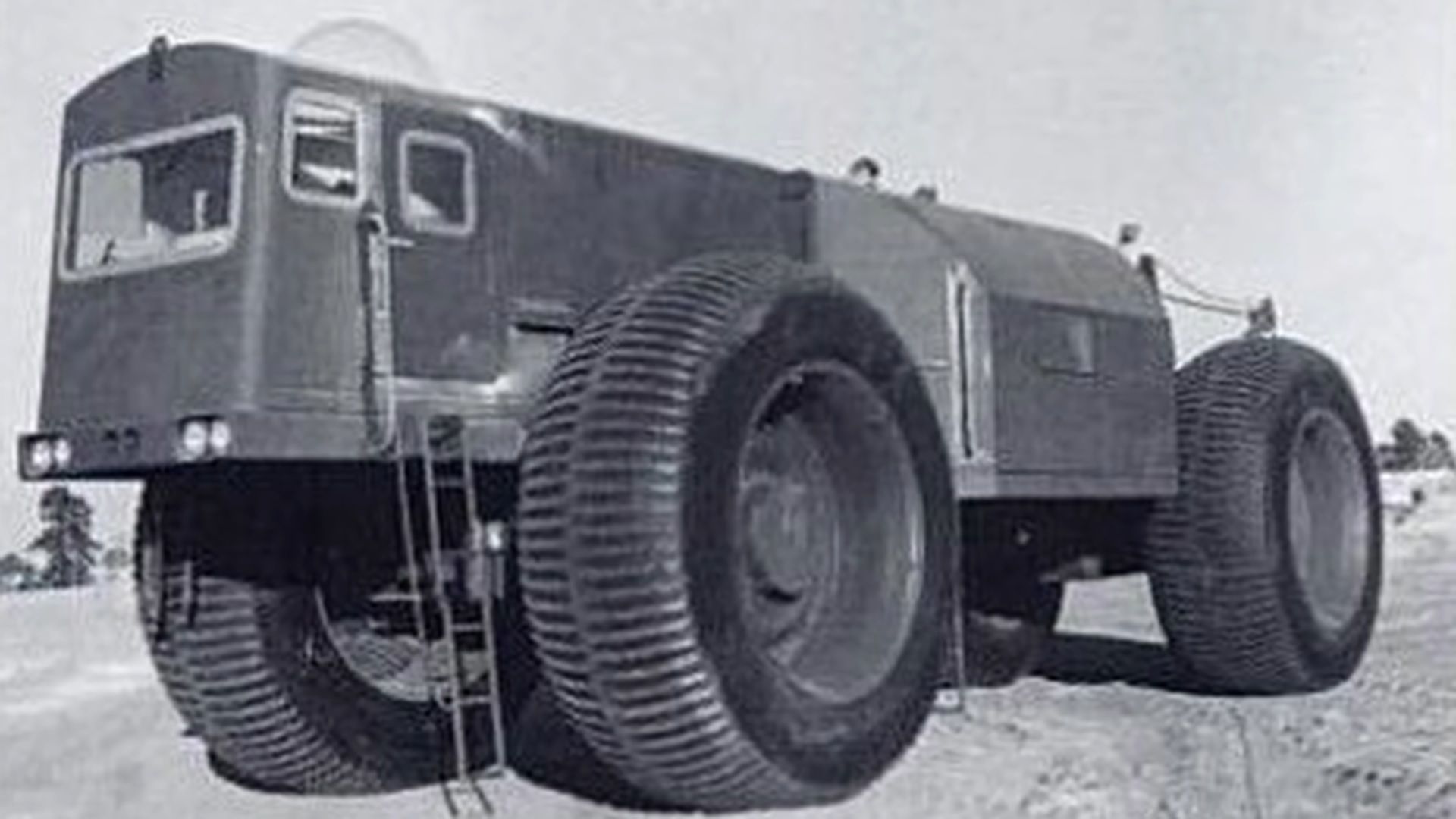

The result was called TC-264 Sno-Buggy. It featured a 28-liter Allison V12 engine running on butane that powered a generator which in turn sent juice to four individual hub motors, each spinning a pair of huge, 10-foot-tall wheels.

The Sno-Buggy didn’t have a suspension system, and instead relied on the low-pressure tires to cushion the ride. And speaking about these immense tires, four of them made their way on the famous Bigfoot monster truck in the 1980s, but that’s a different story altogether.

Getting back to the Sno-Buggy, it was tested in Greenland in April of 1954, where it excelled on the soft snow and ice, thanks to the exceptionally large contact area on the ground. Subsequently, both the US Army and Alaska Freightlines, the company contracted by Western Electric to transport their freight up North, were so impressed with the Sno-Buggy that they ordered a pair of overland trains. Less than two months later, the Alaska Freightlines VC-22 Sno-Freighter was done, and in February of 1955 it was sent to Alaska to start hauling 500 tons of equipment for the DEW stations.

The contract called for a single locomotive and six cars able to haul 150 tons, cross rivers up to 4 feet deep, and operate at temperatures as low as -68 degrees Fahrenheit or -55 degrees Celsius.

The Sno-Freighter did its job as it was supposed to, successfully hauling freight to the DEW Line for its first season, but a year later it was rendered inoperable after it jackknifed and a fire started in the engine room. Not too long after, the contract between Alaska Freightlines and Western Electric ended, and the VC-22 was pulled out of Canada and eventually left on the side of the Steese Highway in Alaska, near the town of Fox, where it still sits today. You can even see it on Google Maps and Google Street View.

But this wasn’t the end of the LeTourneau massive land trains. Remember how the US Army ordered one?

The U.S. Army’s LCC-1 Land Train

Well, sometime after the Sno-Freighter was completed, in January of 1956, the Army’s machine was also finished. It had the same 10-foot wheels that wowed officials a couple of years earlier, but this time the locomotive at the front was able to articulate. LeTourneau called it the YS-1 Army Sno-Train, but the Army referred to it as the Logistics Cargo Carrier, or LCC-1.

Whatever the name, it was powered by a 600 horsepower diesel engine that sent power to all sixteen wheels, and it was capable of hauling 45 tons, which is a lot less than the previous VC-22 that was left at the side of the road in Alaska. But unlike the VC-22, this contraption served a longer and more successful service life, being dispatched in Greenland, where it hauled cargo all over the region from 1956 to 1962.

At the end of its life, it was abandoned in a salvage yard in Alaska for some reason, but luckily it was saved from the crusher and put on display at the Yukon Transportation Museum in Whitehorse, Canada, where it’s also visible from space on Google Maps.

The TC-497 Overland Train Mark II – the Longest Off-Road Vehicle Ever Made

This was the fourth installment of LeTourneau’s crazy land trains, but the US Army was so impressed with the capabilities of the LCC-1 that it ordered a successor. A last hurrah for this unmistakable piece of equipment, so big that it became the longest off-road vehicle ever made: the TC-497 Overland Train Mark II.

In other words, it was a massive, 54-wheel-drive land train. Power for this behemoth came from four, 1,170 horsepower gas turbine engines that were scattered across the train, with one in the locomotive and the other three in their own separate cars. The hub motor system was retained from previous iterations, and it helped the Overland Train Mark II to haul 150 tons at 20 mph for almost 400 miles on even terrain.

But here’s the catch - the train was engineered to accept, at least theoretically, an infinite number of cars, which means more fuel cars could have been added to increase the range, and more cargo cars, and more engine cars, and so on. The gas turbine engines were much smaller than the previous diesel units, and this meant there was a lot of room inside the locomotive. Construction was completed in 1961, and in the next year it was handed to the Army and shipped to the Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona, where it performed well.

The Land Train Was Replaced By Helicopters

But in the end, after all this effort creating a one-of-a-kind machine, the US Army retired the Overland Train Mark II, mainly because newer, heavy-lift helicopters like the Sikorsky Skycrane were faster and more efficient at hauling stuff. After sitting unused for a number of years, it was put up for sale in 1969, but nobody bought it, presumably because of it 1.4-million dollars asking price. Eventually, all the cars were sold off to a scrap dealer, and all that remains is the control cab, which is on display at the Yuma Proving Ground Heritage Center.

The Mark II and its predecessors represent an impressive chapter in the history of huge machines, but I’m curious to find out what you think. So let me know in the comments below.