Often, motorcycle designers go under the radar. There are a select few whose impact on motorcycling has been such that they become household names among enthusiasts. With the Ducati 900SS, 999 and MH900e in his CV, Pierre Terblanche is one of those designers who is firmly in the spotlight, not least for his outspoken opinions that fly in the face of accepted wisdom.

2021 Interview With Ducati Most iconic Designer: Pierre Terblanche

- Make: Array

- Model: 2021 Interview With Ducati Most iconic Designer: Pierre Terblanche

- [do not use] Vehicle Model: Array

The Designer Who Helped Shape Ducati

Pierre Terblanche needs no introduction to motorcyclists the world over. Following stints with Ducati, Royal Enfield, Confederate and carbon fibre experts BST, his designs have helped shape the face of motorcycling, not without their fair share of controversy along the way.

Growing up in Uitenhage, South Africa, his love of motorcycles started at an early age.

“A mate’s father had a couple of race bikes in the garage and I was fascinated by them. My own father had no interest whatsoever about motorcycles, so it was really the neighbour who sparked my own interest. I was fascinated watching the neighbour and his sons - my friends - working on them.

“I bought my first bike, which was a 50cc Honda, which was soon traded up for a CB100 Honda - doubled the horsepower to 8bhp!

“Then I started buying Cycle World magazine and saw my first Ducatis; it must have been the early 70’s. And then there was the Steve Wynne/Mike Hailwood Ducati in the late 1970’s and I became a Ducati fan.”

What came first, an interest in design or engineering?

“I was always interested in the engineering; that was the fun part but, of course, then you have to clothe them in bodywork, so it was a combination of the two elements. The first thing I ever did was to design and make a new seat unit with bum-stop for a friend up the road on his horrible second-hand Honda or something. We made a mould out of clay and then the final piece in fibreglass. Then I designed a fairing for a Suzuki Katana 650; not an official project but just something I wanted to do and a Suzuki dealer in Cape Town lent me a brand-new bike to use, which was either foolish or naive of him.

Cars, Briefly, Then On To Ducati

“Then I worked for VW on car stuff before moving to Ducati to work on the restyle of the 907 Paso - a new fairing and front end - and then the 888 Ducati was the first whole bike I did. At the time, Massimo Tamburini was still a year away with the 916 and the factory needed something to sell, so they came to me and asked if I could restyle the 851 in three weeks. That became the 888.

‘I moved to Varese in Italy to work for Cagiva and started work on the Ducati Supermono; the first all new bike I did. It was a clean sheet job; they gave me a chassis and said; ‘off you go!’ We completed it in three months, all by hand!

“Then I designed the Cagiva Canyon, which was to be a 125cc, 600cc and 900cc. The 125cc never made it to production but the other two did and they were very good bikes.

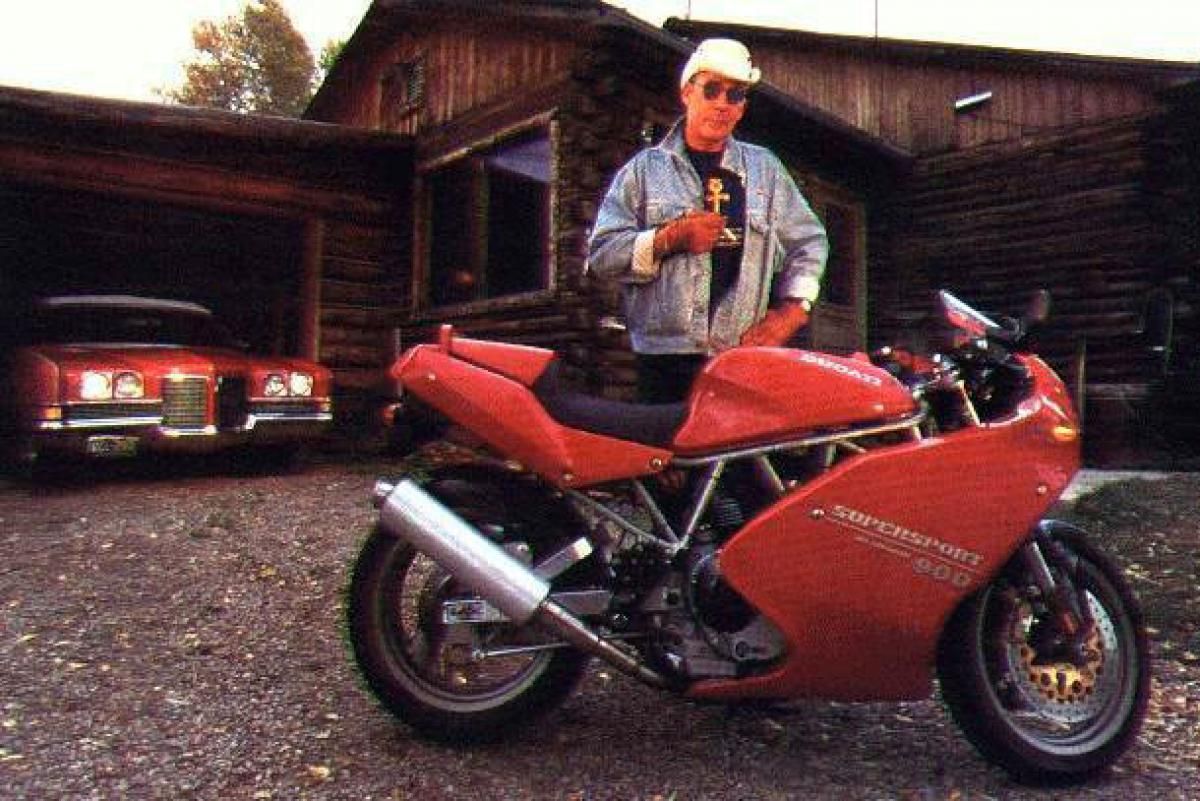

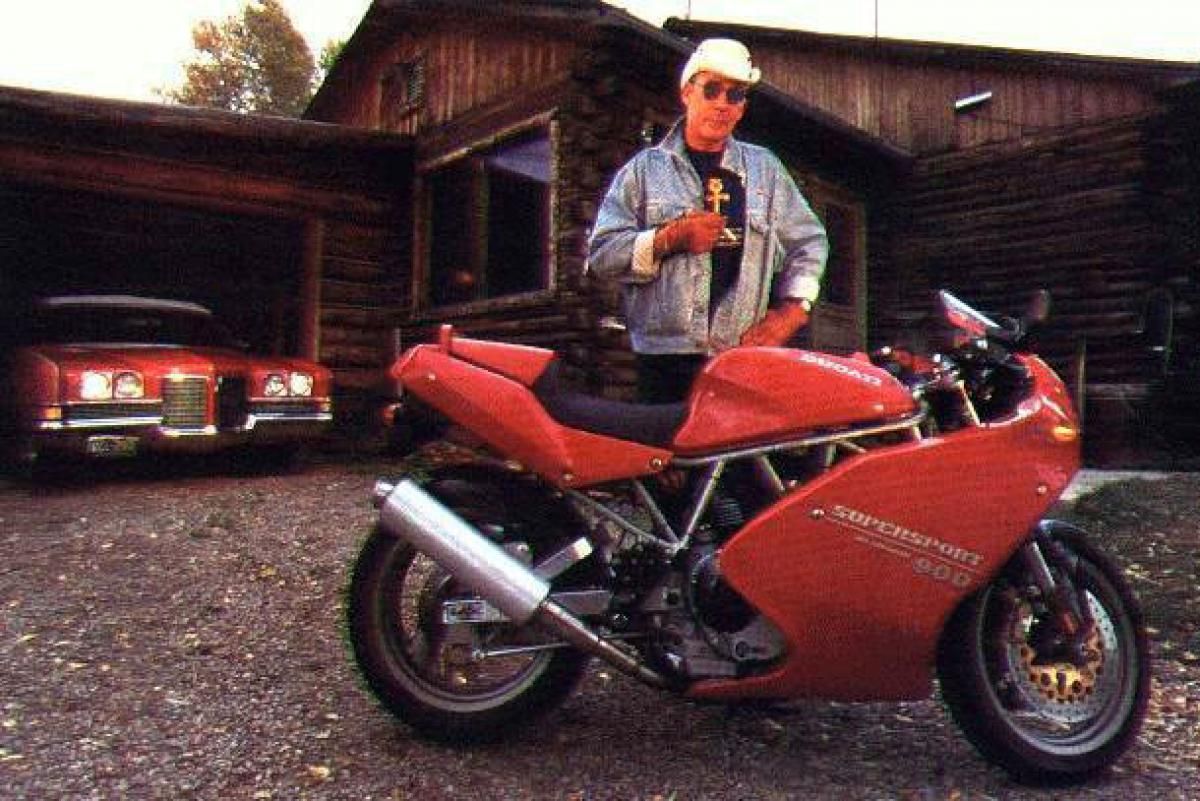

900SS and 999; Starting to Define The Ducati Style

“Back at Ducati, I did the 900SS - another three month job! - which must have been in 1990 or so, then came the 999 but then, four months into designing the 999, the boss came to me and said Ducati desperately needed a show bike and there was only three and a half months in which to do it. I said I could do it but only if no-one at Ducati knew about it or was involved; then it would be impossible.’

The MH900e; the Hailwood Replica Brought Up To Date

This was the genesis of the MH900e, a passion project for Terblanche as his favourite Ducatis are the original MHR900 - the Hailwood TT replica - and the TT600; there are elements of both in the MH900e. Pierre would work on the 999 during the day, the MH in the evenings and then, at weekends, fly to England to a company he had found who could machine clay into any shape from drawings, full size. The chassis and swing-arm were designed and built in Holland, made from drawings faxed to the engineer there.

Interestingly, the original design for the MH900e had a double-sided swing-arm but, because it was a show bike, Pierre decided to go the whole hog and design a single-sided unit, built up from tubes. “It was an emotional thing; it just made the bike look special.”

With the design of the MH900e, it was all about taking the past and moving it forward into the future; it wasn’t meant to be what he calls a ‘curated’ replica of a 1970s bike as is happening with so many retro designs today; “they are simply regurgitating old designs rather than bringing the styling or the concept right up to date. They are familiar, which is what a lot of people like, but they aren’t advancing any concepts as originally incorporated into those bikes when they were new or even being designed as modern iterations of those concepts.”

To Royal Enfield

When he went to the UK to work for Royal Enfield, he was actually meant to be working for another company building a new version of an iconic British v-twin-engined bike from the 1950s. The project fell through, almost to Pierre’s relief as he realised that people would have expected an identikit version of the original. His argument is that the original was the highest expression of technology at the time and therefore, so should the modern version. “That same designer wouldn’t have built it that way today; it would look completely different.”

It’s a theme he warms to as we talk; that many companies are locked into particular designs by the pressures of marketing. He cites the BMW boxer twin as a case in point. “In the 1920’s, a boxer layout made sense for ease of cooling the cylinders. But, with the advent of liquid-cooling, the advantage is lost and you are left with a huge lump of an engine which is compromised in many ways, especially from a ‘breathing’ point of view.”

Strongly Held Views; Is the V-Twin Rubbish?

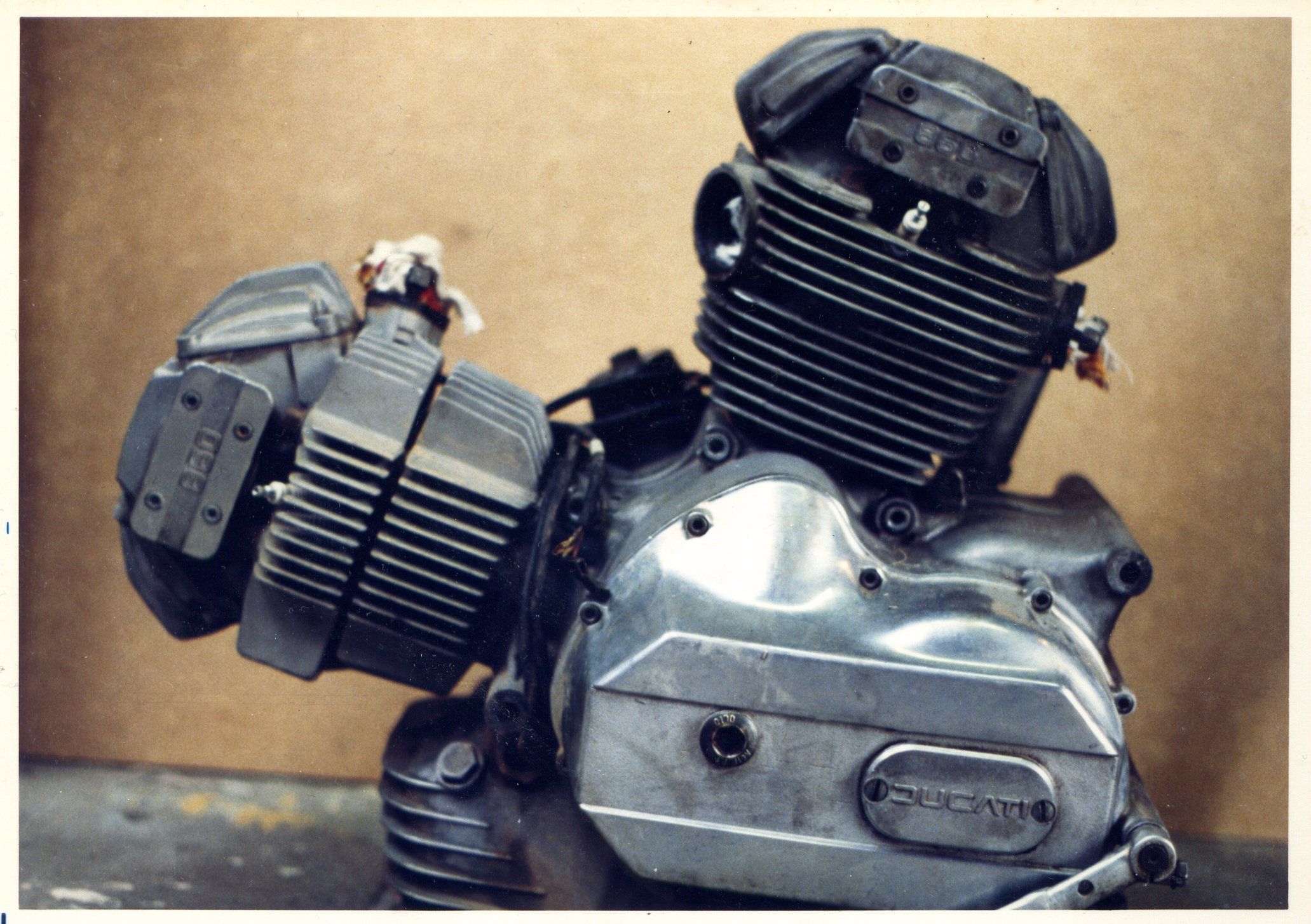

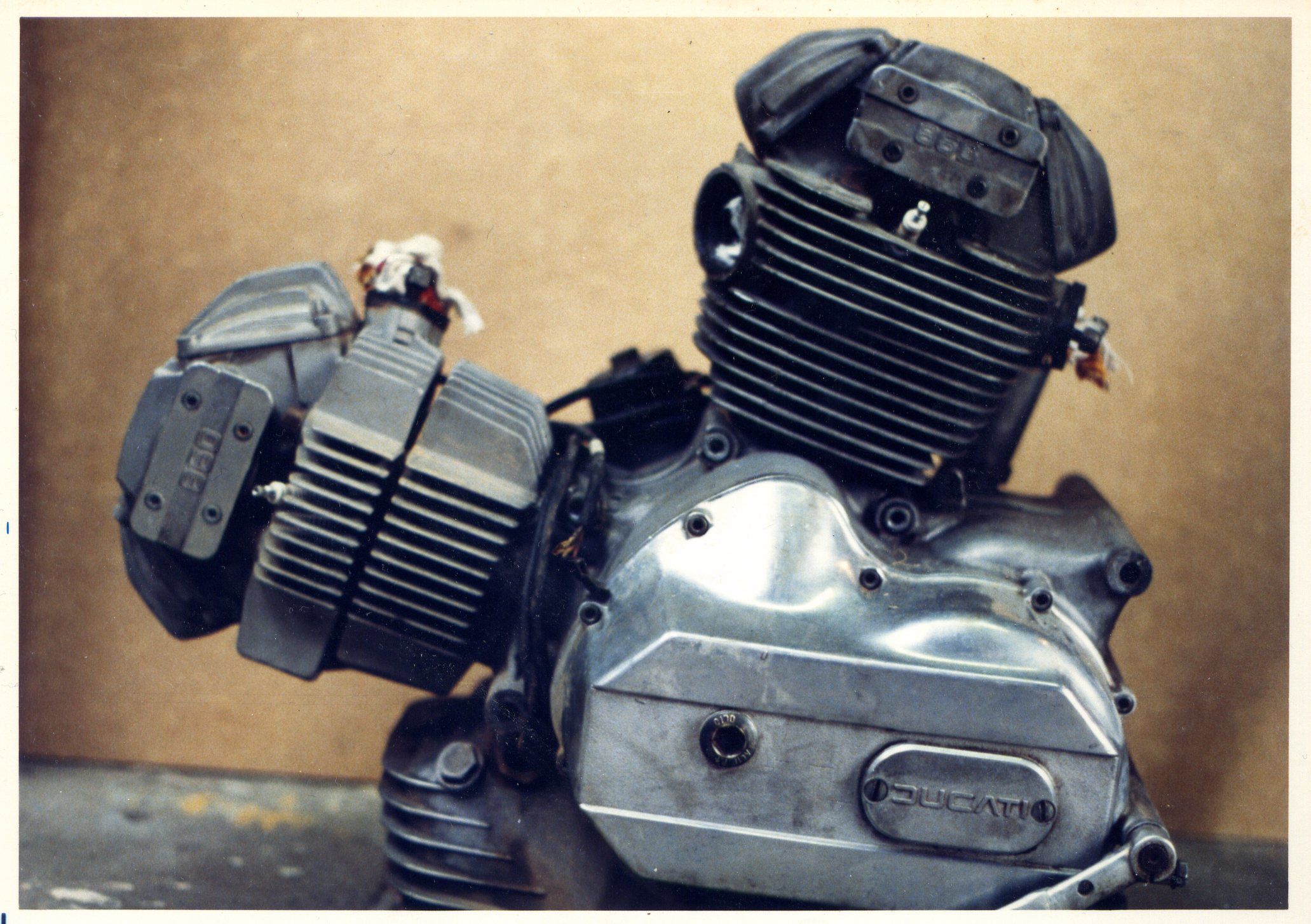

He holds similar views on the V-Twin engine; it can never be the optimum design because of the packaging problems inherent with such a layout, from overall dimensions to problems with intake and exhaust packaging. A parallel twin is much better from an engineering point of view. Even the Ducati 90° v-twin doesn’t escape criticism.

“Ducati’s v-twin made sense when it was introduced; they had a single-cylinder engine and simply grafted a second cylinder onto the crankcase to make a new engine. Because it was air-cooled, the wide-angle made sense but nowadays, it doesn’t make sense at all; you’d design something completely different.’

Because of the explosion in electronics and all the gubbins that need to be housed, ‘traditional’ designs such as v-twins don’t make sense any more;

‘If you have a v-twin and you took away the vertical cylinder and moved it next to the horizontal cylinder, you’d have so much more space to package all the stuff without having to have all sorts of tupperware boxes hiding everything on the outside of the bike.

“I mean, why build a v-twin these days? You’d have be a moron to build a v-twin; it makes no sense technically and packaging wise; they’re heavier, more complicated, the exhaust systems are crap, the intake systems are crap; everything about a modern v-twin is bad. There is no saving grace. Nothing makes sense except marketing.”

Could Ducati Ever Not Make A V-Twin?

Does that mean that a company such as Ducati could never move away from a v-twin?

“They could if they made a great bike. I think that if a company with a great brand strength like Ducati couldn’t build an incredible bike and sell them, they should stop making bikes! It just takes a bit of courage to say, ‘OK, we’re going to build the best bike on the market and never mind tradition.

“They could make bike without a V-twin. They can make anything they want; it’s up to them. But, unfortunately, in the modern day world, it is not what is the best bike but what is the best marketing; what is the aspiration of the rider? Do they want a v-twin because of the way it looks or would they accept something different if it was just as good to ride?

“Is a brand strong enough to do something new? It probably is. Are they too scared to do it? Most likely, yes. The manufacturers are locked in by the marketing. I don’t think anyone soon is going to do the best bike they can do; they’ll do the bike their clients’ demand, which is not always real engineering or design because it’s often not the best solution.

“I’m not sure the market would allow people to do really clean-sheet designs. It would take a very brave management to say, ‘let’s try and do something that’s actually going to be a great bike. People don’t actually want great bikes, they want something they think they want.” In many ways, he says, the tail is wagging the dog . “I’d be impressed if somebody designed a bike that had 85 -100bhp and weighed 150kg and which would be quicker around any race track than the same rider on a superbike. The smaller bike would be so much more efficient, but it’s not about efficiency, it’s about impressing the consumer.”

Why wasn’t the 999 Liked?

Getting back to his own designs, I pointed out to him - not that it needed doing - that not all of his designs have been well-received.

“Well, let’s go to the nitty gritty, shall we; the Ducati 999. I still have haters who blame me for that bike! The headlights come in for particular criticism but what most people don’t realise is that, in the US, there were laws that said you could only have headlamps along a vertical axis; MV had them, so did Aprilia, until the Japanese came along and lobbied the Americans to make them horizontal again. In the meantime, the 999 was meant to have a single light, with one bulb handling dipped and main beam and we could have found the right unit but the Italians, for whatever reason, couldn’t be bothered so we ended with two lights stacked on top of each other.

‘When you’re a designer, you make a choice and you go and try and do something; sometimes it works, other times not so well. People love to hate the 999, even though it outsold the previous bike by quite a lot and, actually, it was a very good bike.’

But was the 999 A Bad Bike?

This is borne out by the fact that many contemporary road tests praised the bike very highly; MCN in the U.K. called it "simply the best V-Twin on the planet", and Motorbikestoday.com described it as "the most desirable, most exciting road bike on the planet". MotorcycleUSA.com described it as "stupendous" and "the epitome of V-Twin power.” It was also very successful in racing, winning the World Superbike Championship in 2003, 2004 and 2006 and the British Superbike Championship in 2005.

Single-Sided or Twin-Sided Swing Arm?

The original design had a single-side swing-arm, but the race department tested the bike and demanded a twin-sided swing arm as a last minute change.

“These were the same guys who couldn’t get a race bike to handle in five years of MotoGP, don’t forget, but let’s not talk about them too much! So, I took all the blame for the lack of single-sided swing arm. Then, the guy who later put the single-sided swing-arm back got a medal for his work! I have to laugh about it because it’s so ludicrous.

“If you look at it from a purely technical point of view, a single-sided swing-arm is heavier; not as stiff for a given weight. But then look at the BMW GS with shaft drive and a single-sided swing arm that weighs as much as a small cow and yet it still sells in massive numbers.

“I received an email from customer saying; ‘I don’t give a f*@$ if a single sided swing arm weighs 6kgs more, I want it!’ That, in essence is why they put it back, because the demand was there. On a purely technical level, the engineers were right but on an emotional and aesthetic sense, it’s what people want.’

Who Were His Design and Engineering Influences?

It’s only natural that Terblanche was influenced by other motorcycle designers, but I wasn’t expecting the list that he reeled off;

“The designers I love are Phil Irving, who did the Vincent, Joe Craig who worked for Norton, Edward Turner of Triumph and the Moto Guzzi designer Giuglio Carcano. I think Guzzi have probably done the most innovative bikes as a company. I don’t think there is anything they haven’t done. They’ve done longitudinally mounted in-line fours, they did a 120° v-twin way before Ducati did one, they did singles and, of course, the V8 500cc race engine, which took them only 6 months from beginning with a blank sheet of paper to running engine.”

The big difference, he says, is that all the designers he named did the whole bike.

“Nowadays, bikes are designed by individuals working in their own little bubble. The engine designer does his bit and he gives it to the chassis guy who has to design the chassis around the engine architecture. Then it goes to the styling guy who has to stick bodywork on it. Then the electronics guy has to cram all the systems in there and somehow make it all work.

“That’s not the way they worked in the past. Turner, Craig and all those guys did the whole bike themselves and I think that’s why the bikes worked; they were a lot more integrated and now, because every element is so specialised, with teams of maybe 50 people working on a bike, it can’t happen. The bikes are all bitty and often are terribly difficult to work on because one guy didn’t consider the problems that the next in line had to face.”

Ducati Hypermotard

It’s clear that Terblanche has done his best work when left alone to do it his way. The MH900e was one example but there is also the original Hypermotard.

“I had a budget to do whatever I wanted and I didn’t have to talk to anyone in the company about it and we did the Hypermotard in three or four months. Nobody saw it until it was finished. When we showed it to Domenicali, boss of Ducati, he asked me, ‘why isn’t it water-cooled?’ Now, I knew him quite well and I had hidden a radiator behind the curtain. So, I pulled it out and said to him, ‘well, find me a space to put it, then I’ll explain to you why its not there!’ Not good politics, maybe, but it proved a point. The whole idea was that the bike was small and neat; a radiator would have completely spoiled that.”

The point was further proved when the second generation Hypermotard lost much of the rawness of the original but then the third generation went back in essence to the first generation.

Which Modern Designers Have Inspired Pierre Terblanche?

I asked him who are the modern designers who have inspired him?

“Well of course, there is Tamburini, my boss at Ducati and John Britten but, I love the older designers mainly because they were able to try new stuff; push the boundaries. New bikes only show incremental improvements; nothing really new has come in the last 30 or 40 years; designers today tend to take an average of what is working elsewhere and just go with that. But it’s understandable; why try and reinvent the wheel? If Honda Yamaha or Suzuki spent twenty years designing a cylinder head and refining them, why would you try something different, what would you achieve? Nothing. So they become very standardised.

“There’s very little design inspiration at the moment. I’m waiting for someone to surprise me; I haven’t been surprised in twenty years. Bad bikes are built because of the limitations of the people in charge. I think the managers are the biggest problem. If they let the designers loose, every new idea would be properly considered but because they have these monkeys in charge who want to build the same stuff they’ve built for 50 years because they are protecting their jobs by protecting the profits of the company.”

To say he is outspoken would be an understatement. He holds his views passionately and isn’t afraid to talk about them, no matter who they might upset. It’s refreshing in a world of ‘yes’ men.

Having worked with Ducati, Moto Guzzi, Norton, Royal Enfield and Confederate, I had to ask him where he thought he might go next? However, he was very coy and simply said that we would have to watch this space. One thing came out though, that he wants to do something very close to what he thinks a motorbike could be as far as purity and functionality goes; a clean sheet design. Talking to him, it’s very clear that he feels that modern bikes are too big, too heavy and even too powerful, whilst also not being innovative enough. You get the feeling that he would be the designer to really take bike design in the direction it should be going and not the direction the manufacturers tell us it has to in order to sell motorbikes; get back to real engineering and real design and not a marketing-lead product.

We have to hope that, one day, we get to see the fruits of his fertile imagination, for the benefit of motorcycling.