At the dawn of the modern era of Japanese motorcycles, the four-cylinder inline engine was king, but that didn't stop Suzuki going off at a tangent with a rotary-engined bike.

Suzuki RE5 - Blind Alley or Brave New World?

The history of motorcycling is essentially the history of the reciprocating internal combustion engine; in other words, an engine with pistons going up and down, in a bewildering variety of configurations.

The internal combustion engine has its drawbacks, however, not the least being vibration. To that add weight, bulk and inefficiency for a given capacity and it’s a wonder that the ICE has been persevered with for so long, especially when much better alternatives became available.

One of those alternatives - and one which was touted as the future of motorcycling - addressed all those problems and yet made barely a ripple on the waters before disappearing altogether.

I am, of course, referring to the Wankel rotary engine.

In the early 1970’s, all four of the major Japanese manufacturers had Wankel-engined prototypes or plans for such, but in the end it was only Suzuki’s design that saw the light of day in the form of the RE5.

As mentioned, the advantages of the Wankel rotary engine were many; better power-to-weight ratio, a third of the size for an equivalent power output, no reciprocating parts therefore no vibration, much higher revving, less components and so cheaper to manufacture and supplying torque for two thirds of the combustion cycle rather than a quarter for piston engine.

The disadvantages referred to issues in sealing the combustion chambers on the rotor, both at low and high revolutions, slow combustion due to the shape of the combustion chamber, poor fuel economy and high emissions due to unburnt fuel entering the exhaust.

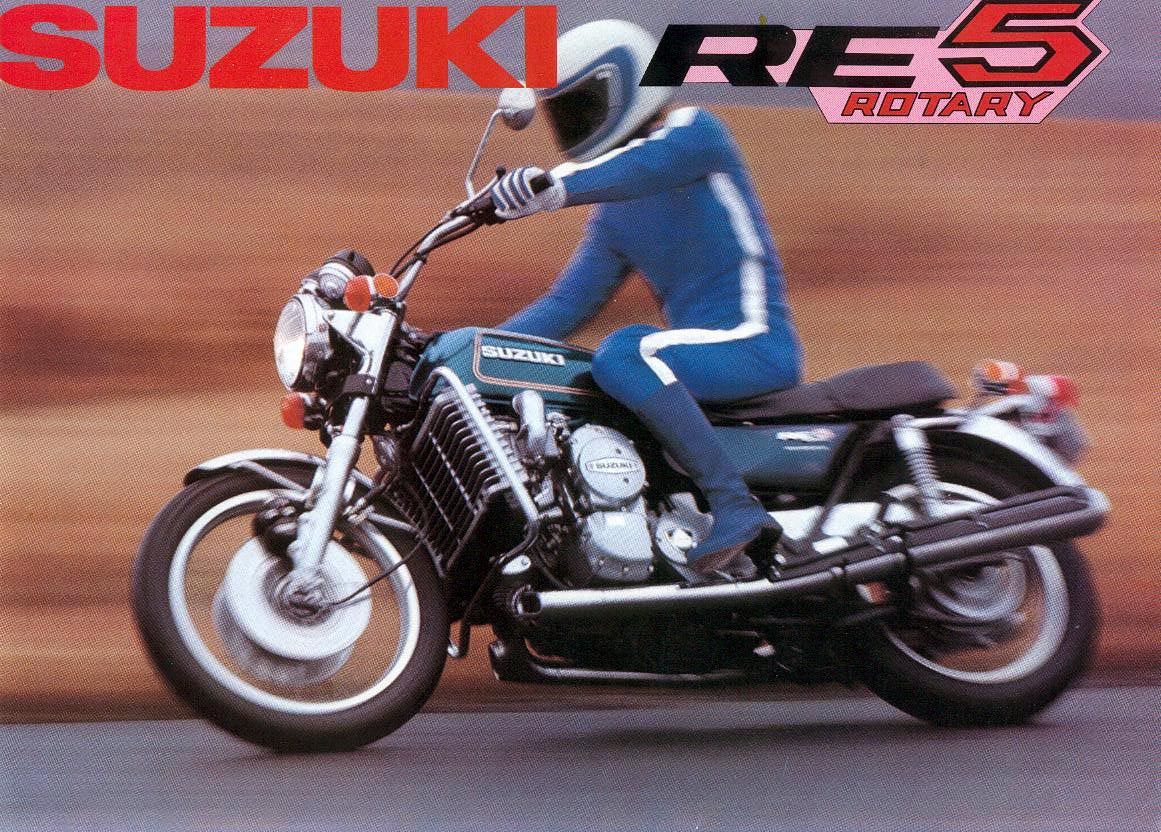

Nevertheless, Suzuki persevered with the RE5, employing Italian industrial designer Giorgetto Guigiaro to design the external aesthetics, with mixed results, including the ‘tin can’ instrument binnacle and tail light. Later models resorted to GT750-style instruments, headlight, indictors and tail light.

The main problem with the RE5, ironically, was the complexity and weight of the engine installation. Rotary engines produce a lot of heat, so the RE5 had water and oil cooling and double-skinned exhaust pipes. There were three oil reservoirs for sump, gearbox and total loss tank with two oil pumps for main bearings and inlet tracts (to lubricate there rotor tip seals - hence the total loss oil reservoir). The twist-grip throttle controlled five cables - the primary carburettor butterfly, a second valve in the inlet port manifold and the oil supply to the combustion chamber - and the carburettor was far more complicated than for a reciprocating engine.

The RE5’s frame and suspension were conventional and reviewers remarked on its good steering and handling, along with good ground clearance. Indeed, it was seen in some quarters to be the best-handling Japanese bike at the time.

However, in time, the handling was seen to be its only winning factor, the engine proving to be underpowered, especially in an overweight bike. In 1985, American magazine Cycle World criticised the RE5 as being ‘complicated, underpowered, and hideous,’ declaring it to be one of the ‘ten worst motorcycles.’ Don’t hold back, then!

In Suzuki’s defence, the RE5’s warranty was, for the time and even now, unusually comprehensive, with a full engine replacement for any engine problem within the first 12 months or 19,000km, evidence perhaps, that problems were foreseen and that working on the rotary power unit was not something that could be entrusted to even dealer mechanics.

In the end, approximately 6,000 RE5’s were produced in two years, 1974 to 1976. In the end, it was simply too complex, to slow, too ‘dirty’ and maybe just too different to really catch on, especially as Suzuki’s Japanese rivals (and Suzuki themselves, it must be said) were making great strides with the then relatively new (but more conventionally acceptable) breed of reciprocating multi-cylinder engines.

The RE5 remains, however, fascinating glimpse into what was seen at the time as a revolutionary step forward in motorcycle engineering.