Motorcycle rear suspension took a long time to catch up with front suspension. For many years, it did not exist at all before plunger-type suspension made an appearance in the late 1930s. Triumph's Edward Turner thought he could do better while still ignoring the relatively new development of the swing arm rear suspension. The result was the Sprung Hub, with springs being housed within the hub itself, which allowed it to be fitted to existing frames and thus requiring no expensive re-designs.

Triumph Sprung Hub Rear Suspension

In the dawn of motorcycling, many things that we now take for granted on a motorcycle either hadn’t been invented or were deemed unnecessary. Chain drive, electric lighting, gearboxes and no-loss lubrication, to name but a few, were all developments that were quickly adopted, however, once they had been developed.

In the area of suspension development, the motorcycle manufacturers were notably backward. Front suspensions were almost universally adopted before World War One - mainly of the ‘girder’ type - but it wasn’t until after World War Two that rear suspension became widely utilised. Prior to that, rigid rear ends were the norm, with the saddle being sprung to insulate the rider from road shocks.

In the late 1930s, ‘plunger’ suspension was starting to make an appearance on the rear wheel. The vertical movement of the rear axle was controlled by sets of springs above and below it, mounted in extensions of the rear frame either side of the wheel, to control movement both up and down. It could be quite sophisticated, with springing and damping in both compression and rebound but there were problems with the system. Wheel travel was limited, the wheel could move out of the vertical axis and it was expensive to produce and difficult to maintain.

Edward Turner of Triumph might have been a visionary when it came to the design of the Triumph parallel twin engine but he was a bit more blinkered when it came to frame and suspension design. In coming up with the sprung hub design, he believed that, for effective rear wheel springing, the amount of travel wasn’t important but the manner or characteristics of the movement was. Thus, the short 2 in. travel of the sprung hub was sufficient.

He originally laid the design out on paper in 1938 and was looking for rear springing that added little weight and complexity and with little additional cost (he was always obsessed with costs). Furthermore, although he didn't say so, any design that left the sleek lines of the Speed Twin intact would definitely be an advantage.

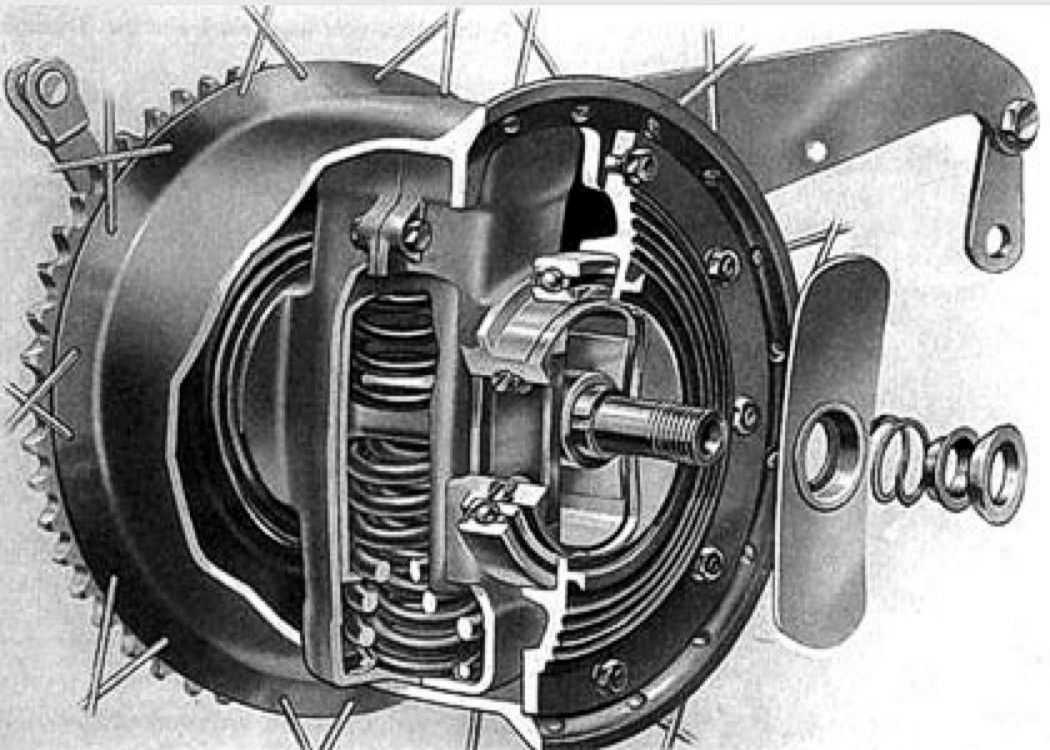

The design was inspired by Dowty aircraft landing gear hubs with suspension within them, as used in the fixed landing gear of the Gloster Gladiator fighter aircraft. Turner's design used a plunger-type suspension made small enough to fit inside the wheel hub. With one spring above the rear axle and two below, the sprung hub provided about two inches of vertical travel and weighed about 7 kg more than a conventional hub.

War prevented the sprung hub appearing until 1946, when it was first seen on Ernie Lyons’ Manx GP-winning bike. However, war had had another, more drastic effect. Material shortages were rife and the idea of developing all-new frames and suspensions - and even completely new bikes - just wasn’t on the cards. Also, the majority of production was for export so UK motorcyclists were forced to make do with pre-war machines.

The advantages of the sprung hub were that it was designed to allow rear suspension to be offered optionally without altering Triumph's existing frames.

Also, existing rigid frames could be retro-fitted with it; owners could buy it and bolt it straight into their pre-war machines to bring them up to date. Another advantage was the large drum brake that was able to be incorporated into the hub.

It would be fair to say that reaction to the sprung hub wasn’t exactly positive. Frank Baker, head of the Experimental Department at Triumph, tried to convince Turner that the handling of Triumph motorcycles at the time the sprung hub was available was potentially dangerous at speed. Turner ignored Baker's advice. It has also been described as "one of the weirdest and worst rear suspension systems of all time."

The sprung hub is remembered as one of the first motorcycle products to have a safety warning cast into its housing. Unless you have all the right tools and knowledge, stripping a sprung hub can be perilously dangerous due to the high tension springs that lie within. In other words, don’t try this at home!

By 1949, the writing was on the wall for the sprung hub as the McCandless brothers took their design for a swing arm rear suspension to Norton, who used it to impressive effect on their new ‘featherbed’ frame. This was so successful that the suspension concept became universally adopted, although it wasn’t the first time a swing arm suspension had been used on a bike.

That accolade goes to Velocette who fitted three race bikes with the suspension in 1936. Of course, the swing arm needs spring/damper units and these were the brain child of Harold Willis, Chief Development Engineer at Velocette. He was a keen amateur pilot and got the idea from watching the action of oleo-pneumatic aircraft landing gear manufactured by…Dowty!

Thus, you have two companies being inspired by the same technology; one is years ahead of its time and the other heads down a blind alley. You never can tell, can you?