Hub-centre steering is one of the few departures from traditional motorcycle chassis engineering that has been paid more than lip service. Bimota still uses the technology but is it just another engineering dead-end?

Hub-Centre Steering: Engineering Dead End or The Future?

Motorcycle development never stands still, although maybe recently, it would be more accurate to say that motorcycle electronics development doesn’t stand still; there is very little in the physical architecture of a motorcycle that is likely to change. But it wasn’t always so and one innovation that was tried not only on road bikes but also 500cc Grand Prix bikes was hub-centre steering.

Hub-centre steering is characterised by the steering pivot points being inside the hub of the wheel, rather than above the wheel in the headstock as in the traditional layout. Most hub-centre arrangements employ a swing arm that extends from the bottom of the engine/frame to the centre of the front wheel.

The advantages of using a hub-centre steering system instead of a more conventional fork are that hub-centre steering separates the steering, braking, and suspension functions.

With a traditional motorcycle fork the braking forces are put through the suspension, a situation that leads to the suspension being compressed, using up a large amount of suspension travel which makes dealing with bumps and other road irregularities extremely difficult. As the forks dive the steering geometry of the bike also changes making the bike more nervous, and inversely on acceleration becomes more lazy. Also, having the steering working through the forks causes problems with ‘stiction’ decreasing the effectiveness of the suspension. The length of the typical motorcycle fork means that they act as large levers about the headstock requiring the forks, the headstock, and the frame to be very robust adding to the bike's weight.

Hub-center steering systems use an arm, or arms, pivoting on bearings at the frame end of the arms to allow upward wheel deflection, meaning that there is no stiction, even under braking. Braking forces can be redirected horizontally along these arms, or tie rods, away from the vertical suspension forces, and can even be put to good use to counteract weight shift. Finally, the arms typically form some form of parallelogram which maintains steering geometry over the full range of wheel travel, allowing agility and consistency of steering that forks currently cannot get close to attaining, despite the years of development.

Contrary to common belief, the concept of hub-centre steering is not a new one. British manufacturer James used it in 1910 and the French Ner-a-Car used it in 1920. But it certainly wasn’t common then and would never become so.

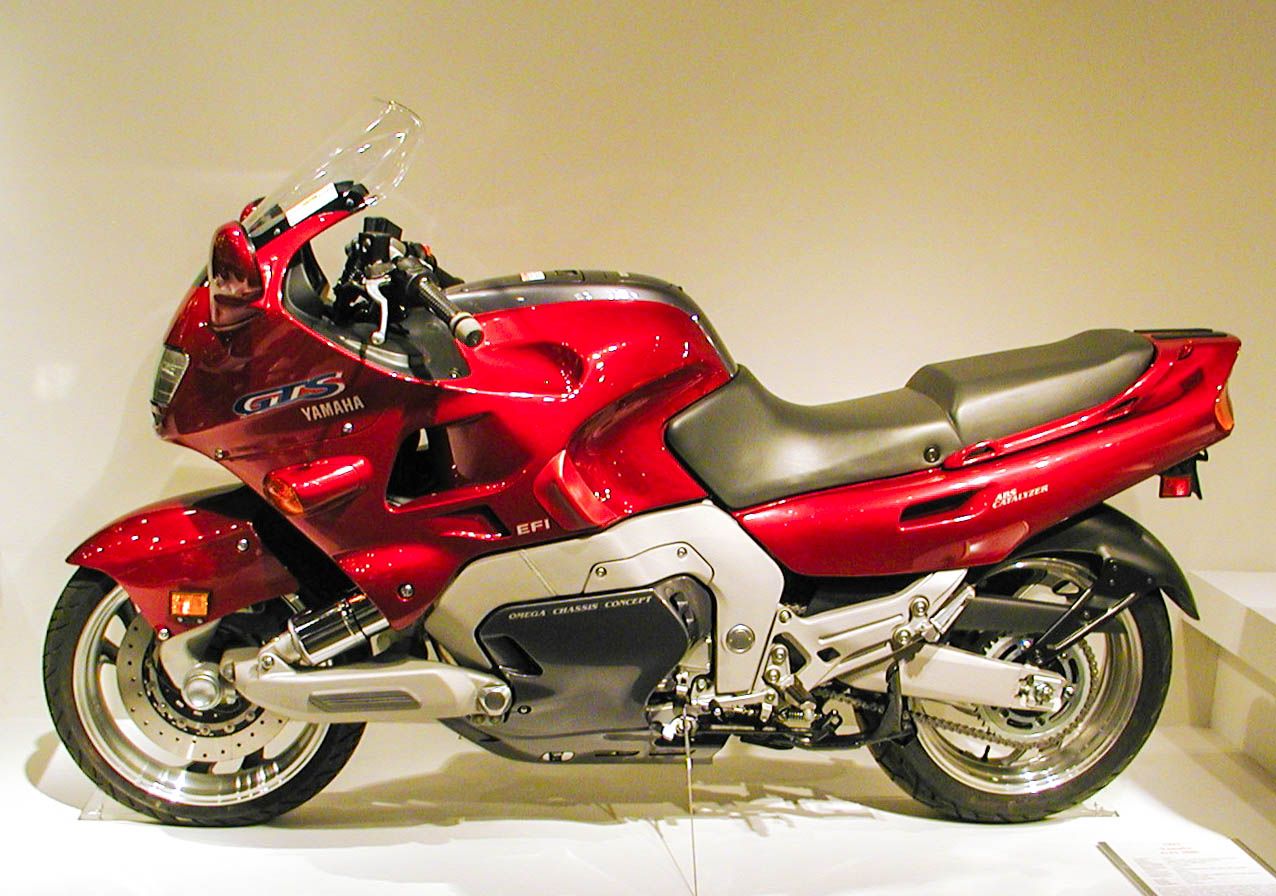

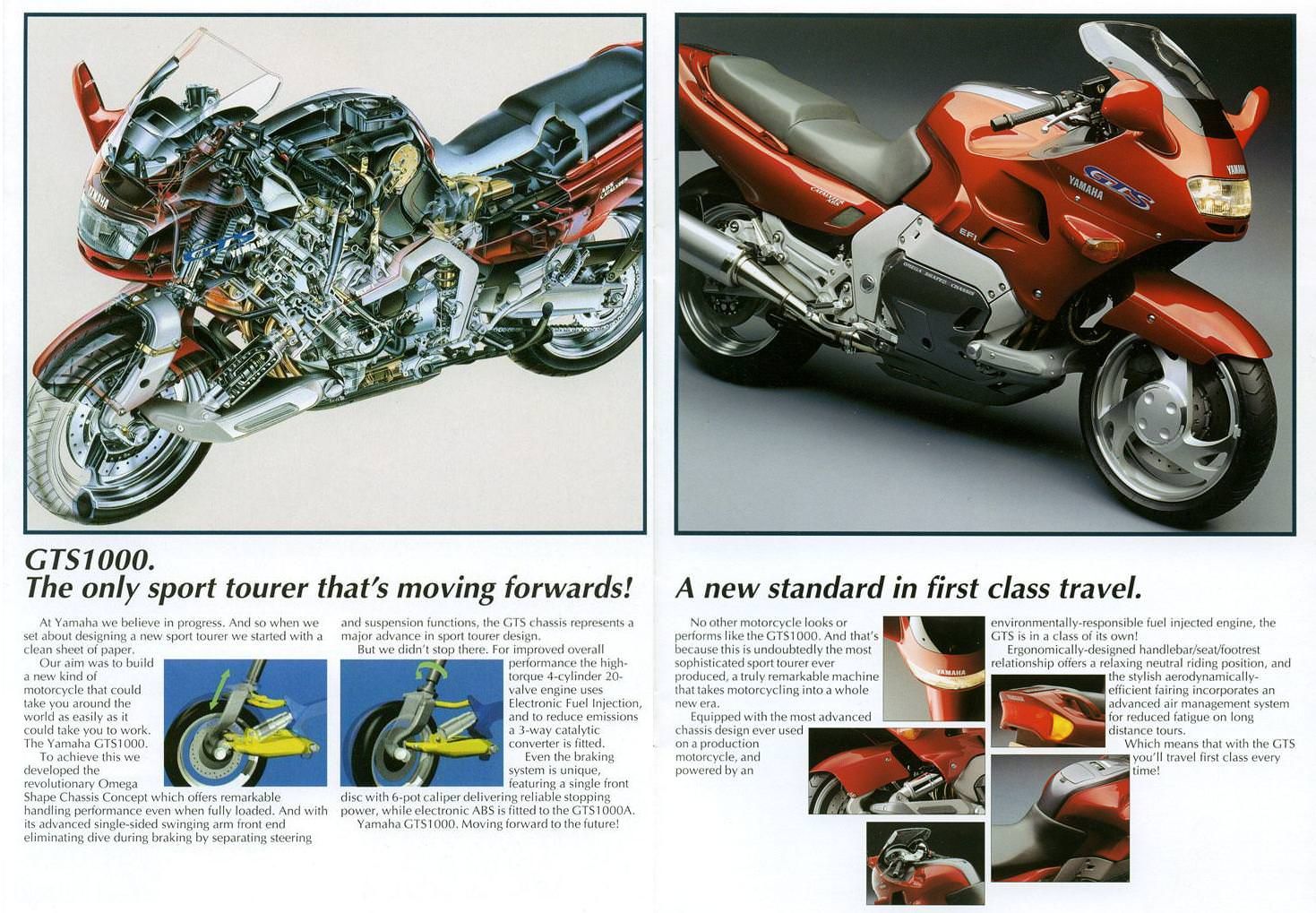

Possibly the most well-known applications in the modern era are on the Yamaha GTS1000 and the Bimota Tesi, not to mention Italjet scooters.

Writing about the GTS1000 in a1993 issue of Rider magazine, author Mark Tuttle outlined the advantages of what was then seen as a brave (and welcome) new direction for chassis design;

“The widely spaced front swing arm pivots spread side and torsional loads over a wider area than traditional steering heads, greatly enhancing rigidity. Bump steer – the tendency of the front wheel to steer the motorcycle as it moves through the suspension travel – is absent since the front suspension is independent of the structure which steers the front wheel. The design is inherently anti-dive as well, since the disc brake caliper is rigidly bolted to the upright. Braking torque from the spinning rotor thus tends to push down on the axle and extend the shock, canceling the forward weight transfer trying to compress it.

“The steering component of this design also requires little space and can be located anywhere within a pretty large area, giving Yamaha more freedom in the placement of critical parts such as the steering head, seat and gas tank.”

Pretty convincing stuff so why didn’t it catch on? Well, quite apart from cost, the hub-centre steering's Achilles heel is acknowledged to be a lack of steering feel. Complex linkages tend to be involved in the steering process, and this can lead to slack, vague, or inconsistent handlebar movement across its range.

It has to be said that, after so many years of telescopic forks, people have got used to riding a bike that handles in a specific way, and compromise is part of the experience. Also there is a depth of knowledge known about fork based chassis design that attempts each year to get around the limitations through technological advances on the current system. Thicker and thicker fork tubes are used to reduce flex, special coatings are used to aid stiction, and greater and greater steering angles are used to counteract dive.

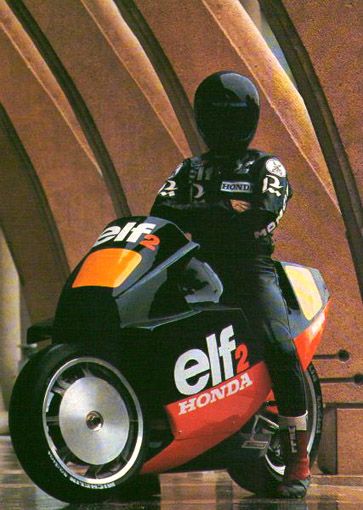

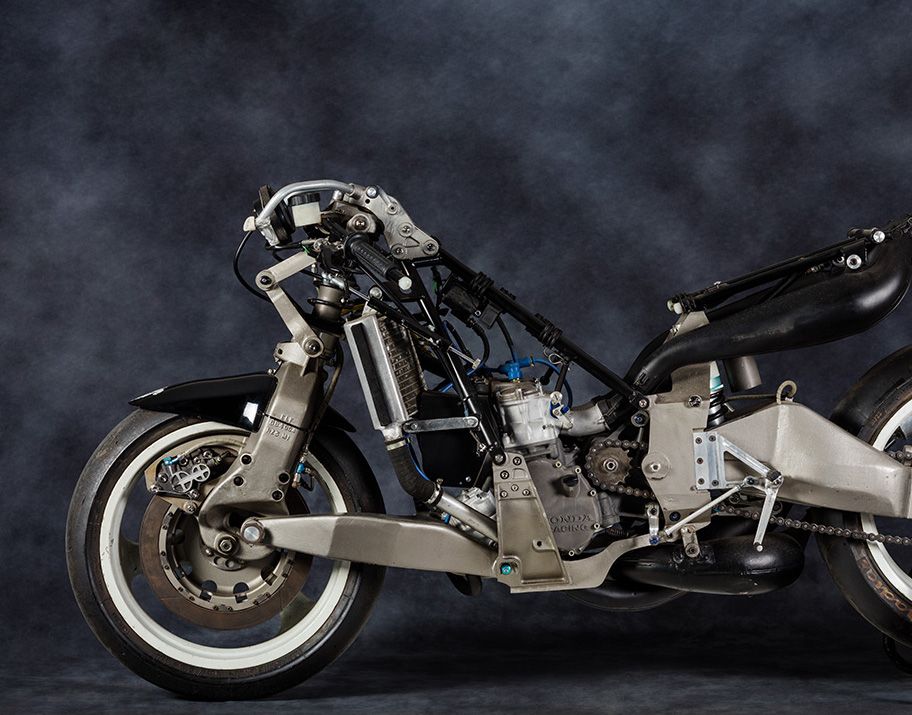

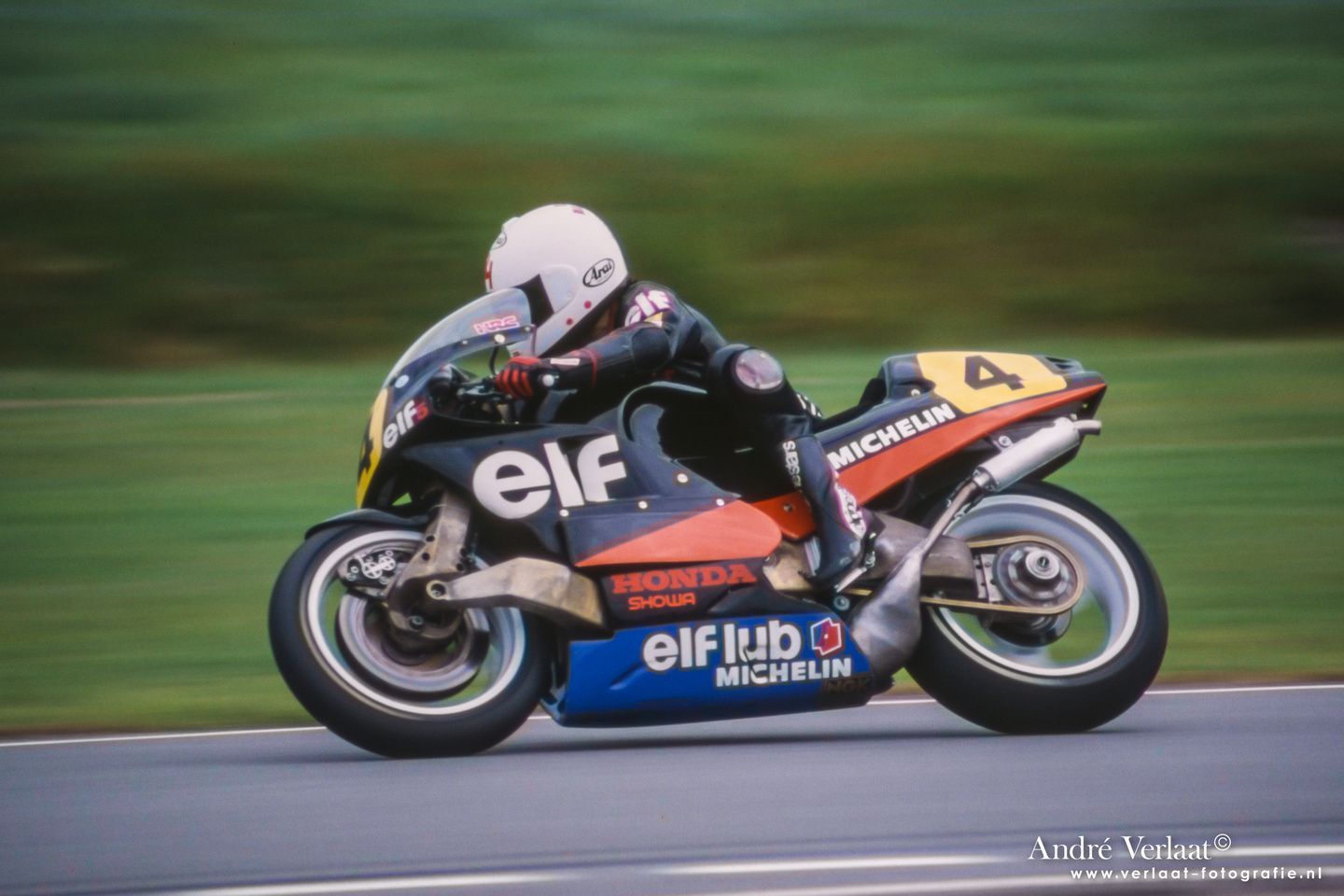

Perhaps the highest-profile use of the system was on the Elf racing bikes, that competed in World Championship 500cc Grands Prix in the hands of Ron Haslam in the mid-1980s. Powered by Honda engines, they were incredible looking machines but ultimately unsuccessful; Haslam finished a few races in the points and even finished 4th in the Championship in 1987, albeit having ridden a ‘standard’ Honda GP bike for most of it.

Was hub-centre steering an engineering dead-end? If we look at the lack of commercial success, then, yes, it was. However, in terms of being an engineering solution, then it was an elegant one and addressed a lot of the problems of forks, certainly 40 years ago, when fork technology was still fairly rudimentary. Even today, advancements in traditional fork technology cannot completely remove the inherent disadvantages of the system, which hub-centre steering addresses successfully whilst perhaps introducing some issues of its own.

The jury is out on this one.