It's one of the most intriguing stories in motorcycling: how did the British Motorcycle industry go from ruling the world to fizzling out with a whimper in one short decade? Many blame the Japanese but, in reality, the British managed the decline all on their own: the only thing the Japanese did was step into the void.

The Decline of the British Motorcycle Industry, Part 4

It’s a story that no-one is unfamiliar with; how the British motorcycle industry withered and died through the 1960s and into the ‘70s. What was once a thriving industry that sold state-of-the-art motorcycles from world-famous manufacturers, by the hundreds of thousands, was reduced to first a handful and then just one manufacturer, producing an outdated design in the face of modern and reliable machines from Japan.

It’s a story of complacency, incompetence, arrogance, poor and short-sighted management, lack of investment and a militant labour force. It’s a story of a government that didn’t care or, when one arm tried to help, the other arm dashed the cup out of its hands.

It’s not as if they didn’t know, those manufacturers. In 1960, Edward Turner of Triumph travelled to Japan to see for himself the extent of the threat the likes of Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha posed. Far from being resented, he was shown great respect as a figurehead of the British industry, which was held in high regard by the Japanese engineers.

Turner, too, was impressed. Upon returning to England, he wrote a report of his findings and it makes interesting reading today, if only for the clear signs that were missed at the time or, if they were recognised, were not acted upon.

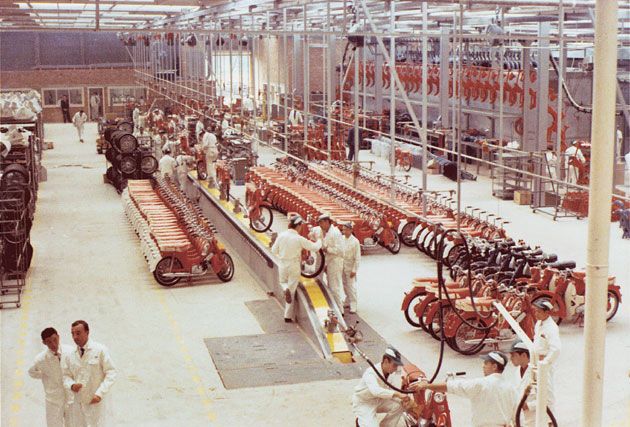

He noted that the Japanese companies were producing 500,000 motorcycles a year, as compared to the 140,000 in England. Even Honda alone produced more than the combined UK output.

Also, he was impressed by the sheer manpower available. “The speed with which the Japanese motorcycle companies can produce new designs and properly tested and developed models is startling and the very large scientific and technical staff maintained at the principal factories is…out of all proportion to anything ever visualised in this country , or for that matter in the US. Honda alone…has an establishment of 400 technicians engaged in studying new manufacturing techniques, new designs, new developments and new approaches.”

It was clear that huge sums of money were being spent on up-to-the-minute factories and assembly techniques, at a time when investment in British factories was declining. Turner also noted that, while the home market might not be affected, there was a need to protect the export markets.

“It is essential that our industry…..should know the facts and what we are up against in the retention of our export markets. Even our home market will be assailed…” However, the next line proved to be a fatal oversight; “…personally, I do not think the Japanese Motor Cycle Industry will eclipse the traditional type of machine that the British motorcyclist wants and buys…” but that “…they are bound to make some impact on our home market by virtue of the high quality of their product and low prices.”

At the time, the UK government had opened up the trade doors to motorcycle imports from Japan whereas the Japanese had made no such concessions. Turner pointed out that, even were they able to export to Japan, they would in all likelihood not make an impact because of the large price difference.

He concluded by saying this; “By and large, the menace of Japanese motorcycles to our own export markets is that they are producing extremely refined and well-finished motorcycles of up to 300cc at prices which reach the public at something like 20% less. The machines themselves are more comprehensive than our own in regard to equipment…….but will not appeal to the sporting rider to anything like the same extent as our own.”

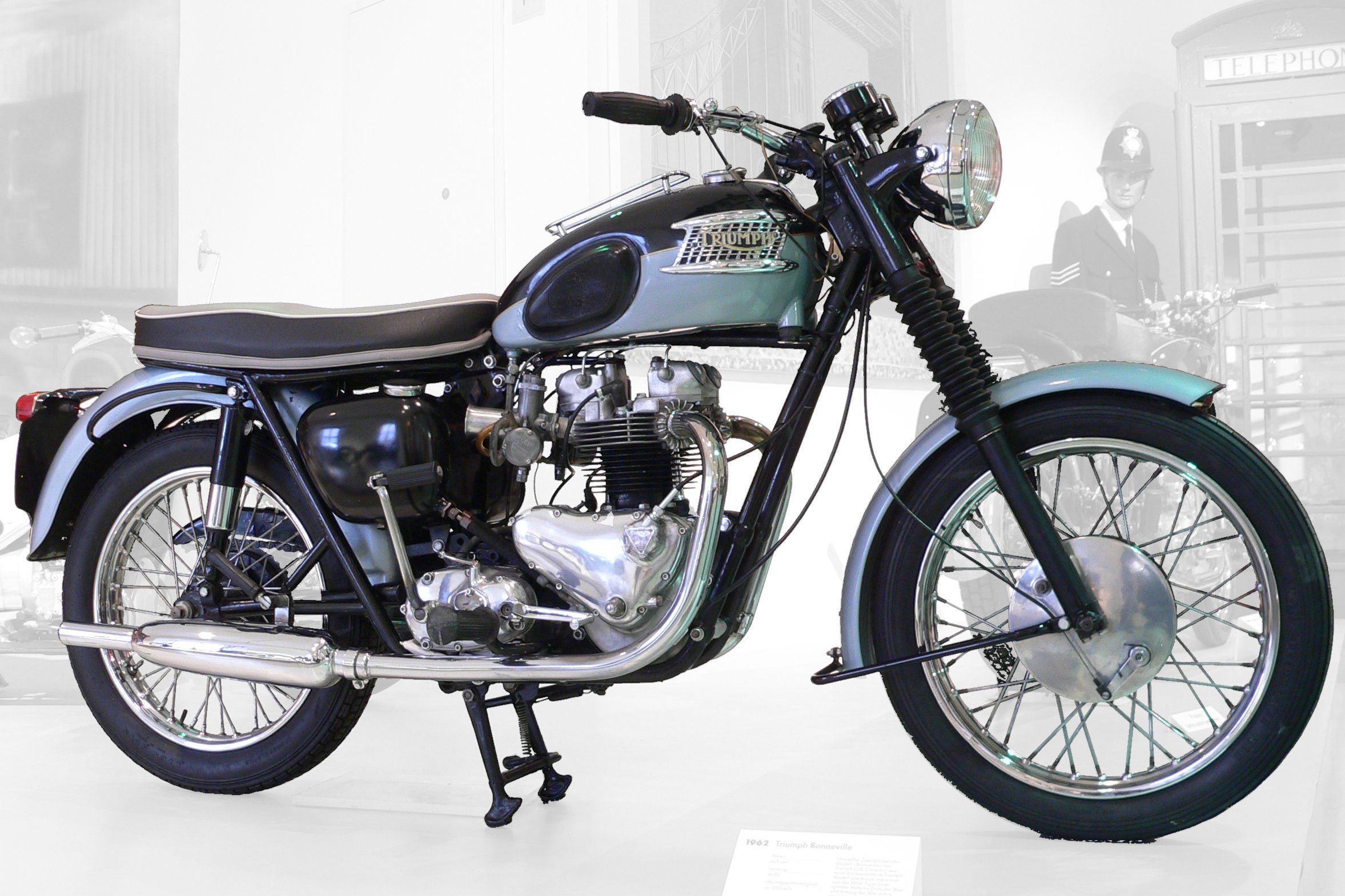

Bear in mind that this was written in 1960, when the British industry was still in good health, with sales of the recently introduced Bonneville, especially in the US, were booming. But the signs were there for all to see.

The problem was, they misread the signs. At the time, the Japanese were engaged in building small-capacity motorbikes and there was no indication that they would move to larger-engined machines. Indeed, the British thought that, far from being a threat, the Japanese would actually help by providing small machines for people to get used motorcycling, from where they would move to larger-engined machines as built by the British.

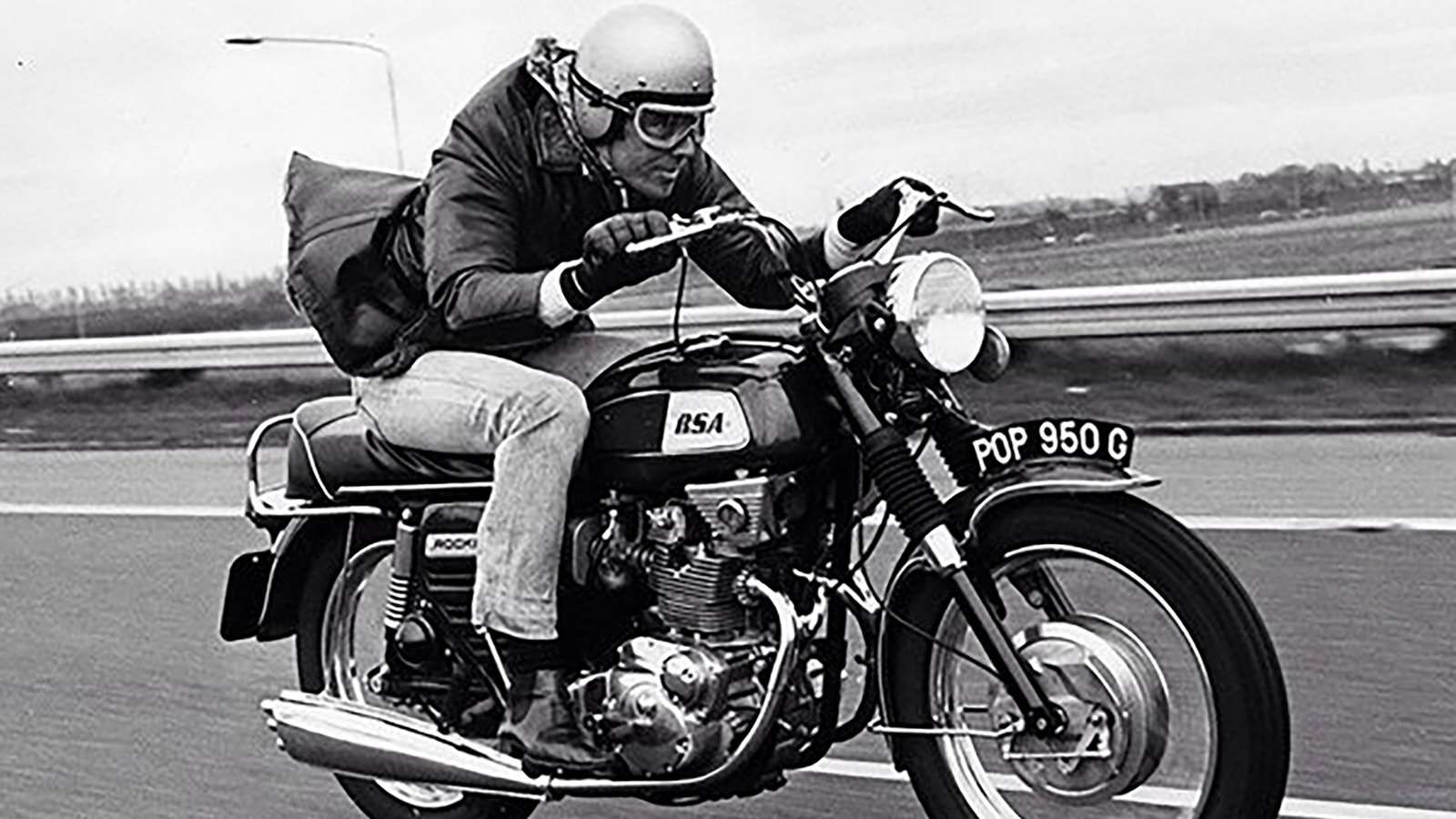

Of course, we all know now that that was wrong; the Japanese came into the large bike market with a bang and swept all before them. It might not have been so bad if the British had a modern range of bikes to counter this attack but they didn’t; what designs they did have to compete with were horribly long-in-the-tooth, unreliable and leaked oil as if it was going out of fashion. Even new designs, such as the Triumph/BSA Trident/Rocket 3, had been rushed into production by incompetent and impatient management and had endless teething problems, not helped by the two versions having many differences in the way the engine was assembled. By the time these had been sorted out, it was too late; people had discovered the smooth running, reliable and fast Honda CB750 and, later, the Kawasaki Z1, not to mention smaller capacity models that lost almost nothing to the large British twins in terms of performance, while being smooth and reliable.

By this time, only BSA, Triumph and Norton were left to fight the good fight; all the others - all those illustrious names and great engineers - had disappeared.

It wasn’t all the motorcycle industry’s fault. Immediately post-war, a motorcycle was still seen as relevant means of transport for the working - and the family - man. The bikes they bought might have been workmanlike and not the stuff of dreams but still they sold in huge numbers. Money was scarce, too, and a motorcycle was a lot cheaper than a car.

But then, the Austin/Morris Mini happened, along with all manner of small cars and, suddenly, young families could drive around in comfort as opposed to in sidecar outfits. Motorcycle ownership started to shrink and no amount of persuasive marketing could stem the flow.

That’s not to say that motorcycling was dying a slow death; far from it. Sales remained buoyant, especially in the larger-capacity ranges and, certainly for Triumph, in the US. Other manufacturers, such as BSA, tended to concentrate on Commonwealth countries for exports, which was, as it turned out, the wrong policy. However, it can be seen that, in the end, neither policy - Commonwealth or the US - worked, and never would in the absence of new models.

That’s not to say that some within the BSA/Triumph conglomerate weren’t trying to do something about developing new models. Turner, now retired, was commissioned to design a new 350cc twin, which was later fettled by Doug Hele and Bert Hopwood, two of the best motorcycle engineers Britain had ever produced. It never made it beyond the prototype stage, nor did a range of modular engines that would have been crowned with a V5 unit.

It would be easy to assume that, by 1970, a year after the Honda CB750 had been launched (despite earlier thinking), that the likes of BSA, Triumph and Norton were dead and buried. However, they were not, with BSA selling 35,000 units, Triumph 38,000 and Norton 10,000. But BSA was doing its best to mess things up properly, there being a huge sense of jealousy towards Triumph, which was owned by the BSA Group, which clouded thinking. It would take a book to detail the almost unbelievable problems that existed in the BSA Group at that time and luckily several exist, the best being ‘Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry’ by Bert Hopwood and ‘British Motor Cycles Since 1950 Vol.5; Triumph Part One: The Company’ by Steve Wilson, both still available if you look around. They are not happy reading, mind you, so be warned.

In conclusion, and to return to where we started, the implosion of the British Motorcycle Industry cannot be laid at any one particular door, rather it was a combination of many factors, virtually all of which were negative. Weak and incompetent management (that often had little or no interest in motorcycling), lack of investment, labour problems, Governmental interference and inconsistency and an ageing product line. That latter might not have mattered too much if the Japanese hadn’t come along and kicked their arses so comprehensively. But they did and, in one fell swoop, hammered the final nail in the coffin.

It was to be a sad decline but one that has been happily reversed by first John Bloor and Triumph and, hopefully sooner rather than later, TVS and Norton. If the BSA revival happens, then we’re almost back to 1970 and battle can commence again on the showroom floors.